The dystopian information network of Perihelion: The Prophecy

I don’t usually get to talk about games from a librarian perspective, so please indulge me with this one!

Perihelion: The Prophecy, a role-playing game for the Amiga from 1994, is set in a post-apocalyptic cyberpunk wasteland, built atop the ruins of a technologically advanced society that has long since faded from memory in a nuclear war. Although this chaos-riddled civilization continues to research new technology, notably a new field of genetics that bridges the gap between science and religion to engineer cyborgs and artificial life, there still doesn’t appear to be much in the way of meaningful infrastructure that hasn’t just been repurposed from the old world.

One thing they’ve managed to get working is a crude version of the internet called the NetWork. This might be the most plausibly dystopian part of this whole society.

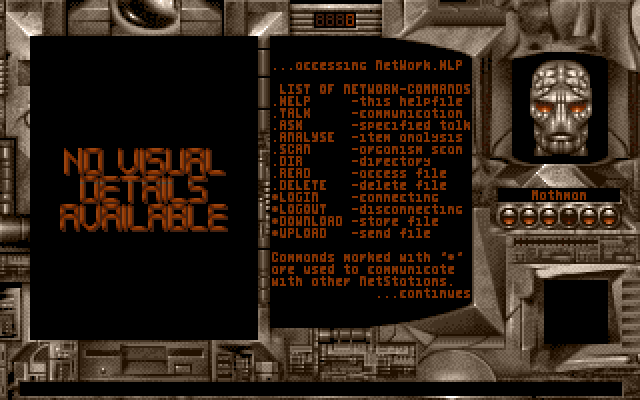

The NetWork is the primary way that people in Perihelion interact with computers. Everyone carries a Personal NetStation – think of it like a post-apocalyptic phone – which they can use to manage their own files, analyze their surroundings, and communicate with people nearby. To access other servers on the NetWork, you have to use a NetStation computer, which are only running in limited quantities across the planet. In the case of either device, the NetWork is a text-only command-line interface. You have to type “dir” to call up a directory of files or “ask” to speak with a person next to you.

From the perspective of playing Perihelion, the NetWork is a brazenly user-hostile way to present information. Text interfaces weren’t uncommon yet when Perihelion came out, and there’s a good chance you’d be familiar with them if you were using an Amiga. Still, the rest of the game uses icons you can click on, and the fact that you need to switch gears to a computer terminal to do things as simple as speak to the person next to you is startling, but exciting. It sells the idea that this awful planet has to make do with systems they aren’t entirely comfortable with to accomplish basic tasks because they don’t have much control otherwise. What alternative to the NetWork is there?

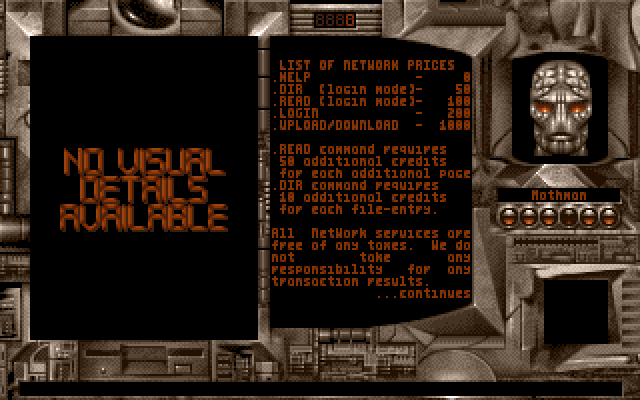

That’s not what’s so dystopian about it. The really horrifying part is that the NetWork charges you in-game currency for accessing information. You pay 200 credits just to log in. 50 credits to retrieve a directory, plus 10 credits for the name of each file in the list. 100 credits per page of every document you read. In a world that seems on the verge of total anarchy ruled by roving criminal gangs and underground psychic cults, not only is somebody maintaining a global interoperable computer network, but they’re profiting off it by monetizing it within an inch of its life so that even accessing emergency information would cost hundreds of credits.

This is the absolute worst-case scenario nightmare for the internet: paying every time you refresh a webpage and paying $1000 to download a text file, because you have no choice, and the money goes into the pockets of some totally unknown, unaccountable organization. It’s surprising that the nearly-lawless world of Perihelion doesn’t appear to have piracy or an underground ring for trading information; even the criminals seem to use the NetWork because there’s no other networking infrastructure.

Who’s getting rich off information in the post-apocalypse?

This seems ridiculous, though in 1994, it might not have looked so impossible. Even though Perihelion was developed in Hungary, and I don’t know enough about early 90s Hungarian internet infrastructure to comment on that, a pay-per-use internet lines up with how early dial-up ISPs like America Online, CompuServe, and GEnie charged per hour for access to their walled-garden services, rather than a flat monthly subscription. The NetWork might have been an extension of what the developers imagined the internet in the 90s could eventually become, something closer to a toll service than an open network.

In fact, metered information ecosystems similar to the NetWork already exist today, in microcosm, in the form of closed-access information services. The closest parallel to the NetWork today is PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records), a government service that charges per page for court documents or even to retrieve information about what court documents are available. The other strong comparison is scholarly publications and digital resources at libraries, which sometimes employ a “patron-driven acquisition” model that charges libraries based on how often or how much of a document, film, or book is used. This is meant to be flexible and save libraries money, but if it’s heavily used, it can end up being equally or more expensive. Libraries and researchers remain locked into expensive ecosystems for accessing information because even though there are increasingly more open-access publications, in many cases like PACER, there’s no alternative.

I think this, at a larger scale, is one of the concerns about the increasingly closed walls of the internet, the idea that we’ve lost control, that we’ve locked ourselves into services so widely used that they almost resemble public infrastructure, and if their owners – or internet service providers – wanted to charge us a la carte to access them, we’d have no other option. It’s not out of the question to imagine an internet provider offering a plan where you pay for a service per file and they sell it as an innovative form of flexibility, like “Uber for information” or something absurd like that.

Of course, the reason that the NetWork has this dystopian pricing model is for gameplay purposes. It’s a terrifically frustrating detail that puts the player in the economy of this terrible future, but it also raises so many questions about the infrastructure in this society. It seems to be borne out of an expectation for how the internet might have evolved based on trends at the time, and unexpectedly, it ends up speaking to fears today about the future of the digital information.

I do really like the deep-dives on a single facet of a game you’ve covered, like the post on Liryl from Lighthouse. The games you cover are so often clearly the manifestation of a neat idea somebody had looking for a home, and those weird glimpses into the mind are a great thing to unpack. Or sometimes an arbitrary part of the game is staggeringly complex for little discernible reason! Both are fascinating.

In Hungary, the public internet was almost nonexistent in 1994 – there was only 45 .hu domains at the end of the year and the whole country’s international data line was 256 kbit/s. In two years the internet was suddenly everywhere, but ’94 was before it was mainstream. (Source: http://nmhh.hu/cikk/192602/Az_internet_hazai_megjelenese)

Second the last comment.

I was 10 in 94 and I’m pretty sure I haven’t seen “internet” until 95-96.

Before that I’ve used a local network in our computer lab (both of these were a rarity back in the country back then), and it was DOS based as I recall.

My first home internet provider was indeed Compuserve for some reason, but that wasn’t common for the whole country. It had both a monthly “base” fee, and in addition to that it used either minute or hour based billing.

Another thing about perihelion:

Many of the faces and characters seem to be based on photographs, or existing artworks (it’s not as bad, as in the better known Arcania games).

I see a couple that were “inspired by frazetta paintings (most likely magazine covers, featuring frazetta paintings).

Another important source to be a book simply titled “people”. There was this series of pocket-size referencebooks about everything ecology and biology: trees, mushrooms, dog breeds, etc, and one of them was a little antropology-tome about different races and their common physiological features.

Most of the illustration within were clearly drawn after photographs, but since there was no internet back the, I’m pretty sure the reference used was not the original photo, but these drawings.

https://ibb.co/BqSdntL