Joining the Video Game History Foundation

Folks, it’s time for some big news…

I am overjoyed to share that I’m joining the Video Game History Foundation as their new library director!

The Video Game History Foundation is a non-profit organization in Oakland, CA dedicated to preserving video game history. Since 2017, the VGHF team has been tackling the biggest questions in game preservation, working with everyone from private collectors to major developers to help save archival materials that tell the story of video games. The VGHF has built an extensive collection of video game-related items — including magazines, press kits, development documents, and source code — that’s currently in their office in Oakland, and as library director, my job will be to transform that collection into a world-class video game history research library.

I’ve been a supporter of the Video Game History Foundation for years, because they’re helping bridge the gap between the game industry, researchers, and the community to help fix the future of video game history preservation. I am proud to bring my years of professional experience in libraries and archives to the cause. It is a privilege and a challenge, and I’m ready for it.

The Obscuritory has been instrumental in getting me to this point. Every project, every panel, every article, whether it was a massive essay about SimRefinery or a random late-night post about Aaargh! Condor, has prepared me to become a professional video game preservationist. If you’ve been to any of the events I’ve mentioned on this blog, you might’ve seen me on panels with VGHF co-directors Frank Cifaldi and Kelsey Lewin. Well, we’re in business together now! We met in person doing panels together at MAGFest, and our paths have been on a collision course ever since then.

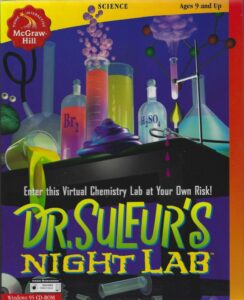

So what does this mean for The Obscuritory? Well, not a whole lot is actually changing. I’ll still be writing about weird old games and doing history research. It’s possible that bigger history or preservation projects might now happen under (or in conjunction with) the Video Game History Foundation, but I’m still going to be exploring CD-ROMs and incessantly writing about Maxis Software on here. Realistically, the biggest change I can imagine is that working full-time on video game history might burn me out on games and push me into non-gaming hobbies for a while. I’ve been getting back into playing trombone again. Maybe I’ll join a ska band?

I feel like I always end announcement posts like this by thanking everyone for reading, but seriously, sincerely, thank you. For the 13 years I’ve been running The Obscuritory, it’s grown from a lark I ran out of my dorm room at 2am to a full-fledged career in a field that didn’t exist when I started. Your support has encouraged me to take this seriously, and now, I get to help build something that’s going to change how we tell the history of video games.

I’ve always prided myself on defining my own life’s meaning. Today, it feels like those years of taking my own path have paid off. I can’t wait to see what we do next.