Securing the open future of “advocateless” game preservation

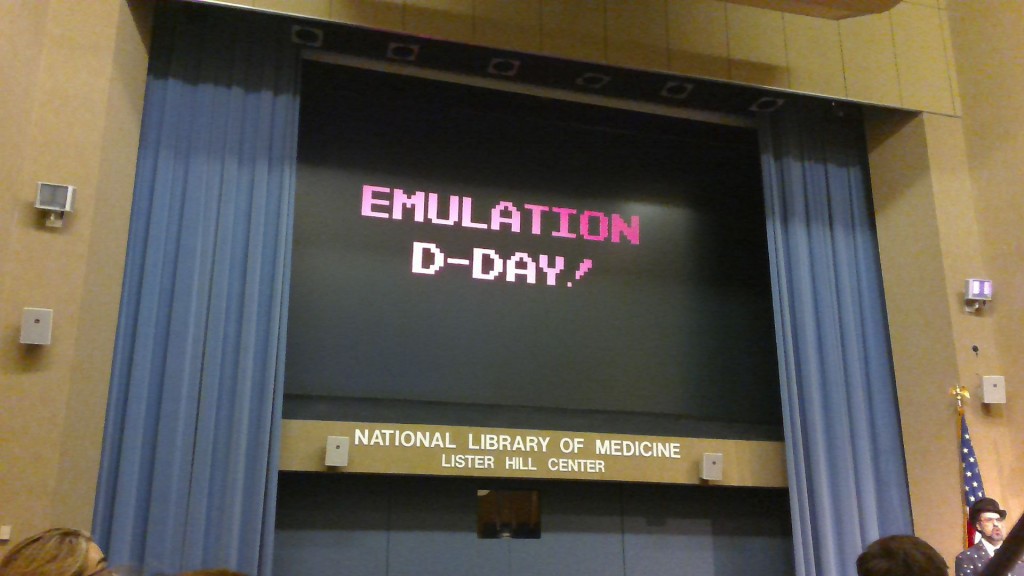

This Thursday, I had the privilege to attend the National Digital Stewardship Residency 2016 Symposium at the National Library of Medicine. The speakers and program residents shared all manner of interesting projects that bridge the gap between digital and physical archiving; for the purposes of this blog, the most critical was the Internet Archive’s Jason Scott’s talk about software preservation. Scott’s work has been pivotal to opening up years of gaming and computer history, and during his appearance at the NDSR Symposium, he spoke frankly about the challenges the Internet Archive faces when their collection comes under scrutiny. His thoughts greatly allayed my concerns about the legality of game archiving, directed the focus of those efforts, and made the case to keep preservation frequent and fearless.

The Internet Archive justifies its massive, free game and software collection (124,000 items as of this post) under fair use doctrine. Essentially, fair use exceptions in American copyright law allow the use and production of copyrighted work for noncommercial, educational purposes that do not impact the marketplace or value of the item. The boundaries of these exceptions are still extremely unclear, so without knowing the particulars of the Internet Archive’s legal situation, their broad invocation of fair use for a gigantic, untested collection scared the hell out of me. Should someone have challenged a game in their DOS library and won – has anyone ever sued an open digital software archive? – it could have had a chilling effect on other, target applications of fair use for preservation.

As it turns out, this hasn’t been an issue because nobody really cared. A year and a half ago, the Internet Archive released emulated versions of over 1000 historical games, including big names like Super Street Fighter II that would inevitably be challenged. This was no accident: Scott says he wanted to test the waters of digital game archiving in the most visible, forceful way possible that would attract the attention of the public and rights holders. About one-fifth of the emulated games were questioned and taken down without argument, but those tended to be lucrative, high-profile titles like Mario and Atari games. Scott said he didn’t really care about preserving them, because for the time being, their owners still have a commercial interest in their continued availability.

Instead, Scott wanted to see what happened to the “advocateless material,” the games and programs without owners who actively care for them. (“Advocateless material” is such a more descriptive, compelling term than “abandonware.”) Almost all of that software stayed online, and some of their creators even celebrated their inclusion on the Internet Archive. Under a massive spotlight, those games remained unchallenged. Scott’s test worked: a public digital archive of obscure, under-the-radar, less-commercial software was viable.

Scott wasn’t interested in going to court to defend the ability to host Pac-Man under fair use, because for the software that needed the most archival attention, that wasn’t even necessary. That’s an invitation to start digitizing and sharing neglected software right in the open. If Microsoft won’t even contest the Internet Archive’s distribution of Windows 3.1, everyone has a license to dig up what they have and make it available before it’s too late.

Innumerable digital information has already been lost. The event participants noted that unlike physical materials, digital items like software can be totally destroyed instantly and can’t benefit from the “benign neglect” of gradual deterioration. The Library of Congress estimates that three-quarters of all silent films have been permanently lost after a century. To prevent another such cultural cataclysm, Scott recommends archiving less methodically and more like an EMT. If we have to wait for permission and improved standards to preserve games, it’ll never get done.

We do still need high-quality metadata to make these items discoverable, because we can never properly use them if we can’t find them. Throwing everything into an unlabeled pile accomplishes nothing for people trying to locate those items. But since digital objects decay more completely than a book or a painting, we can’t keep stalling to save them.

To develop a more complete understanding of game and software history, we need to take collective responsibility for the preservation of advocateless digital material. Thanks to Jason Scott and the Internet Archive’s huge gamble, now we know that we can.