Fooblitzky

Deduction board games permanently live in the shadow of Clue, a masterclass of patient strategy. Knowledge matters more than action in Clue. You can’t organize any sort of power play, and you could feasibly win by watching other players and taking notes. The steady drip of new information allows anyone paying close attention or with sharp logical skills to stay on top.

Almost every game of deduction owes some debt to Clue, and Fooblitzky proudly wears that influence. Created by the complex logic puzzle lovers at legendary interactive fiction company Infocom, Fooblitzky is a shaggier beast than Clue, often crazy, cluttered, and confused where similar games are lean. With so many components to handle in a digital board game, Fooblitzky lives and dies off-board in players’ notepads.

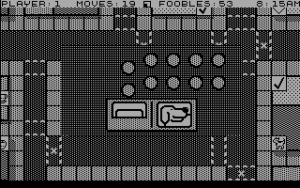

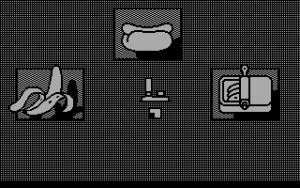

In lieu of a murder mystery, Fooblitzky sends you shopping downtown. At the start of the game, two to four players (represented as a very happy dog) each secretly pick an item from a list of 18 pieces of merchandise; the first person to identify and buy up all those secret items wins the game. Players can deduce those items by checking availability at stores throughout the city. All stores will generally carry one of each theme-relevant item, and if an item is out of stock, it must have been chosen at the beginning. Assorted perils await the dogs throughout the city of Fooblitzky, including reckless traffic that can send you to the hospital and rare visits from the shadowy Chance Man.

Foobles come and go quickly, most often from those visits to department stores. You only have a one-in-six chance of finding a store with such a clue, but you must buy something if you go inside. Inventory space and foobles are limited, so to earn back money and to free up inventory space, you can sell these excess items at pawn shops or donate them to charity. Dogs can also, somehow, work at restaurants to earn extra foobles at the cost of a turn. There’s a slew of other special spaces on the board, like phone booths to check store stocks remotely, lockers that hold your secret items, and a fast-travel subway system.

Remembering what to do and where to go can be taxing, especially given Fooblitzky‘s extremely minimalist interface. The game uses pictographs in place of words whenever possible; this simplifies its appearance, but without descriptive on-screen help or useful data, you need to rely on outside information sources. Expect to consult Fooblitzky‘s rulebook frequently as you learn the ropes.

To make this more manageable, the game originally came with whiteboard worksheets for tracking progress. These are essential. You need to remember what stores carry and who has certain items. Deduction would be borderline impossible without these reference cards / notepads, much more so than Clue. Sites like the Museum of Computer Adventure Game History have thankfully scanned those sheets for future use without needing a rare physical copy of the game.

The decision to put all the stat-tracking off-screen creates an obvious learning curve for first-time players, but the manual note-taking and solving offers a sense of personal reward. Without an in-game display broadcasting known information and player status, making and comparing lists by yourself feels like solving a puzzle and outwitting your opponents – even when everyone playing probably has the same notes as you.

In an unusual quirk, everything that happens in the game (apart from the initial item selection) is openly visible. Assuming all players watch game activity carefully, no one has a substantive advantage in information. Actions do little to benefit individual players. This matches well with Fooblitzky‘s maximalist, kitchen-sink mechanics. The ability to “bump” players and exchange inventories, for instance, is too strategically confusing to be a game-changer. But since you don’t have much to lose, it might be worth trying just for the hell of it to reveal anything that might be a clue. Any open knowledge could be useful, even other players’ store visits that leave them with an unwanted tennis racket.

The overload of board features is still messy. God forbid, if two players pick the same item, store stocks will double, extending the game far longer than desirable. But the semi-collaborative approach to information discovery encourages experimentation since your standing is rarely in jeopardy – so long as you’re paying attention.

And that’s the sticking point. Fooblitzky demands extreme close attention to detail, both on- and off-board. Not everyone will enjoy that, certainly fewer than might pick up the more-accessible Clue. All players need to be engaged, attentive, and well-versed in the rules for the game to work as intended. With a group of friends eager to play who-bought-it (and with worksheets printed out), Fooblitzky could be a hoot. Or a woof. Everyone’s a dog, remember.

(The screenshots in this article are black-and-white, but Fooblitzky does feature color graphics depending on the video mode and hardware used.)

My name is Brian Cody. I was hired by Mike Berlyn of Infocom in late 1982 to create infocom’s first graphical computer game. At the time I was working as a graphic designer and illustrator for textbook publisher Houghton Mifflin and Infocom looked like a fun opportunity to break into the brand new field of computer gaming. Mike formed a small team of myself, game expert Dan Horn and programmer Poh C. Lim to brainstorm what a new type of game might look and play like. It took 6 months of game-playing before I produced the first concept for the animated scavenger hunt that eventually became Fooblitzky. Using a pre-release Apple Macintosh to generate the graphics, I illustrated and animated everything in the game including dogs, Fooblitzky products, Chance Man, game board and even the game’s packaging. I was laid off by Infocom in early 1985.