Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse

The mindboggling part of Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse how much there is. It’s presented as a collection of HyperCard programs from the belongings of an artist named Arthur Newkirk. It includes his digital art books, a fortune telling program, a 52-page article from an academic journal analyzing an album he recorded, his personal correspondences, and a program from a sci-fi convention he attended.

None of it is real. There is no Arthur Newkirk. He never recorded an album. And yet here’s 200 pages of his poetry and essays.

Your family supposedly knew Arthur Newkirk as Uncle Buddy. He disappeared under mysterious circumstances, and in accordance with his wishes, he has bequeathed to you a disc full of his personal items. Wait though. How does he know you? That’s a vague enough name that you could be convinced through the power of suggestion that your family knew someone like him. The letter from the office of Uncle Buddy’s estate carries a bizarre warning: you might not remember Arthur Newkirk because of “‘divergences’ of an unspecified nature.” Divergences?! Like something changed in reality?

Phantom Funhouse has you picking up the documents from someone else’s life, exploring the totally mundane objects that accumulate around you. It has a deeper, darker, surreal motive for exploring that, one that calls the premise of the program into question if you’re inclined to look for it.

Uncle Buddy was mainly a writer, plus a musician for the band the reptiles. He called his work “the intersect of art/zines/sf,” and the computer documents he left behind are pieces of the sort of punk nerdery he specialized in. It’s like you received a folder from Uncle Buddy’s computer.

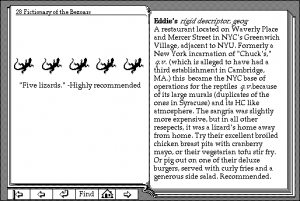

The best entry point into his world is probably what he called the Fictionary of the Bezoars, a dictionary of in-jokes and personal references. Uncle Buddy mocked it up to look like a fake book with a long, nonsensical copyright notice on the inside cover. (“No part of this publication may be read, eaten, or talked about without prior writhing emission.”) It mentions the zines he liked to read, his favorite restaurant and a song his friend wrote about it, clubs he joined at Syracuse University in the 70s, things his friends said (“Eat Fuck!”), and at least one reference to The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai. It has DIY self-made enthusiasm, documenting his own life through slightly subversive creative humor and unconcerned that anyone else would read it.

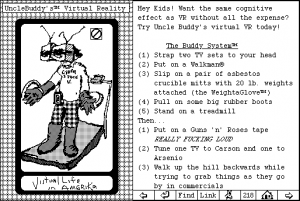

Everything else in Phantom Funhouse reads like a page from some chapter of his life. He wrote Sooner or Later, a crummy science fiction drama screenplay about physicists; it has features to view videos and production notes, which Uncle Buddy never finished, and trying to use them sends back error messages and opens HyperCard’s real debug tools. He wrote a poem for a hacker zine in Adobe PostScript code, which I can’t compile. His modem communications are unformatted and still have all the logs from the University of Rhode Island’s servers from the late 80s. His personalized copy of the atlas program Hyper Earth focuses exclusively on the street Uncle Buddy lived on in the fictional town Pirate Cove, RI (which, in real life, is an unoccupied strip of land off Rhode Island Route 24). His book called The Writer’s Brain has hundreds of pages of free association rambling about writing and philosophy. The program also came with audio cassettes of his music.

In terms of its breadth alone, Phantom Funhouse is quite something to look through. It reminded me of wiki sites like the Hypothetical Hurricanes Wiki or USA Store Fanon, where people have collaborated to make up detailed alternate realities for ordinary topics like weather patterns and retail store locations. They’re unnervingly compelling because of how many hundreds or thousands of entries they have. Why would someone make all that up? They’re like minutiae that somehow crossed over from another universe.

Phantom Funhouse is the same way, but for a character. It recreates the art and the mundane details of an imaginary person’s life, almost like echoes of their life, the liner notes and lyrics from a music anthology you can never listen to. Random details like the movie screening schedule for the sci-fi convention he went to suddenly take on importance when they’re the last artifacts we have from somebody. As he tells it, Uncle Buddy’s life is a collage of references, name-dropping Albert Camus, The Twilight Zone, Let’s Make a Deal, The Sound and the Fury, and Carl Sagan among others. Maybe that’s who he is and how he thinks, or not, but it’s what we can figure out about him. To throw out another name, his life brought to mind a Thomas Pynchon novel, humorously (over-indulgently?) dense with references to concepts that wander back and forth between reality and fiction.

The Oracle program is a grid of black-and-white drawing and poems, some that seem to have a bearing on Uncle Buddy’s world

There’s more happening here, though. Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse has another unsettling layer boiling underneath this, and whether or not it’s worth uncovering depends on how much work you’re willing to put in. Stay with me on this one.

Throughout all his writing, Uncle Buddy has obsessions. He constantly thinks about the medium of his art and the relationship between signs and signifiers, almost self-aware that he’s part of an experimental story filled with references. He keeps writing about time, physics and metaphysics, and the nature of reality, spiritual orders of the world, simulations of consciousness, the concept of the HyperReal suggesting that so much of everyday life is an illusion or an imitation. He implies that his dad also vanished under mysterious circumstances, just like he eventually did. He says that the Fictionary “exists in YOUR particular spacetime. Other spacetimes may be almost identical.”

Think about that in the context of the “divergences.” Is something happening with reality here? As you read deeper, the notions slowly start to creep into the text. At first, they seem like odd topics to bring up, but then you notice them everywhere. It’s bizarre and intentionally unclear, his obsession with parallel realities left to seep quietly into his story. Uncle Buddy seems to realize that he’s not in the same universe as you. He knows that as far as you’re concerned, he’s fake, or at least there’s no way to tell otherwise.

Within this funhouse world of mirrors, Uncle Buddy mentions the idea of a “ka,” an ancient Egyptian concept of a soul’s doppelgänger. His seems to be Emily Kean, the “semi-manager” of the reptiles. He keeps mentioning her. He thanks her in the intro to one of his books, credits her for photos, and wrote the album Emily and the Time Machine about her (Syracuse University professor Dr. Jerome Brentano called it “an interesting array of signifiers, drawn from diverse mystical systems,” because of course that’s what it is). Buried deep within his books is a riddle and a password involving the ka; they lead you to Emily Kean’s parallel universe, Aunty Em’s Haunt House.

Emily’s version of the Phantom Funhouse is darker and wrier, twisting the original ideas. She mocks the “pornography of reality” and compares Uncle Buddy’s work to Plato’s cave allegory, where you are only used to seeing the shadows of real objects. Her personal version of the Fictionary references AIDS, excoriates Reagan-era Republicans, and declares Uncle Buddy a “false generic.” She writes a teasing first-person essay from the perspective of Uncle Buddy calling him “an aging infant” who wrote everything you’ve read so far to “force other people to experience my angst” so they can “re-experience it years after I’m dead.” His stories are cruel illusions, the very HyperReal imitations he was worried about.

In the last pages, Emily and Uncle Buddy both claim that the other is a fictional literary device they invented for their writing. They are both lies. They are each other’s doppelgängers. There is no objective reality.

So that’s a lot to take in.

You can only uncover the twist with a very close reading, pouring through Uncle Buddy’s writing multiple times looking for clues. It does have an option to spell out the answer to the riddle if you want to skip that, but the significance might be lost in the process. Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse demands your time, attention, and energy, but frankly, the amount of bloat discourages that. The Writer’s Brain is excessively long and unreadable, and Uncle Buddy’s music isn’t interesting enough to read meandering critical analyses about. Its achievement in those areas is the depth of the fictional realities it creates, not necessarily their contents.

Phantom Funhouse is for people who want a narrative to push back and refuse to give up its secrets. It’s a character study for the folks who datamine games to learn more about them, and in fact, there’s more hidden in Phantom Funhouse if you attempt to hack it open using the Mac resource-viewing tool ResEdit.

It starts out as an interesting exercise about a sci-fi punk told through his documents and references. It seems like a lot of detail for a fictional world, though, and the longer you stare at it, the more that seems to be point. Can you create another universe through writing? Are the characters we create alive in their own way, and what if they reject us? If someone else read the objects from our lives like they were pages in a story, what would they think about us? Would we just look like a self-indulgent collection of in-jokes and favorite movies?

Uncle Buddy ends The Writer’s Brain with a suggestion that’s more chilling once you’ve read the whole thing: “Sometimes, you can look back on your life and say, as if you were a character, say, in a fiction, what it seems to have been all about.”

If you want to learn more…

In 2015, Dene Grigar and Stuart Moulthrop’s Pathfinders project documented the history of four early multimedia art projects, including Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse. Their work is essential, and it includes an interview with author John McDaid and a video of him doing a commentated walkthrough. Grigar and Moulthrop have gone into way more detail about the program than I have here. It’s a great place to get deeper into the program’s history and themes.

Incredible work of art.

I don’t know if it’s the article which makes it look good or not: I’ve dreamed, and that’s enough 🙂

Odd. ‘Ka’ is an important concept in Stephen King’s Dark Tower books, which also play with the nature of reality and metafiction.

Reading this reminds me quite strongly of the House of Eternal Return, the Meow Wolf installation in Santa Fe. It, too, presents you with a bit of a mystery you can explore in incredibly rich detail from the things the disappeared have left behind. It explodes into gorgeous dreamscapes once you explore beyond the initial set-up, but it is only with that initial research, scouring the seemingly mundane for clues, that the fantastic elements hit their full emotional relevance.

… I feel a bit awkward basically advertising for something that isn’t even a game here, but I really think if you found Funhouse interesting, you’ll get a lot out of it.