The Tone Rebellion

One exercise that’s helped me understand weird games better has been figuring out what exactly makes them weird. Many times, a weird game is actually just a normal game that looks and sounds strange.

The truly weird games have been the ones that operate by their own logic, games governed by rules and systems that don’t jive with the ones we’re accustomed to. My favorite example of this, as always, is Knights of the Crystallion, a “cultural simulation” game that asks you to follow the arcane spiritual practices of a dead civilization in order to make progress. There’s a big difference between the games that simply look unusual and the games that push you to think outside your normal mindset.

Somewhere between those two ideas of weird is the The Tone Rebellion. It’s a strategy game about expanding your empire over vast galactic territory, a genre that was on its way to the point of oversaturation when The Tone Rebellion came out in 1997. But digging past the surface-level clichés, The Tone Rebellion is trying for something grander, steeped in myths and history and alien astrology: a network of symbols and values that begs you to acknowledge them before you can progress.

If you had to pin The Tone Rebellion to a specific genre, it would be a 4X game, a type of strategy game that focuses on expansion, the best known probably being the Civilization games. But this game isn’t about expansion (or exploitation, the slightly regrettable one of the four X’s in 4X) as much as it is about reclaiming what was lost.

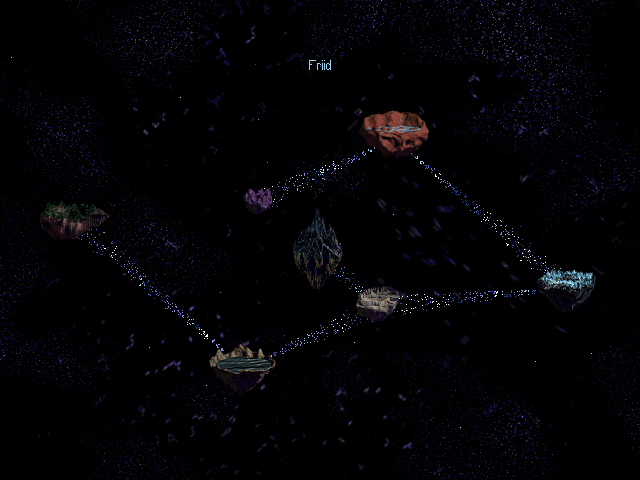

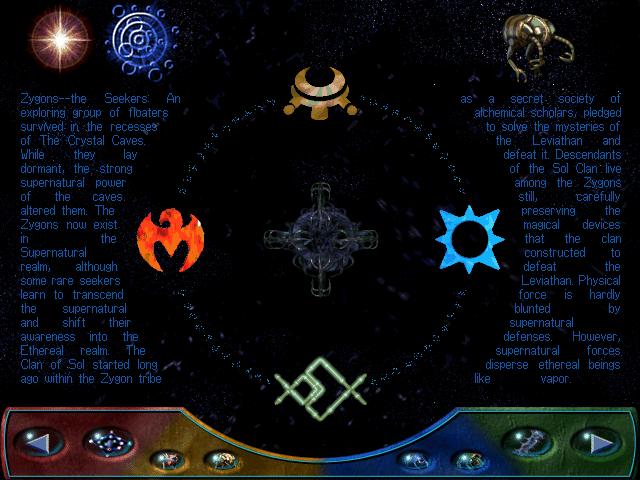

Long ago, in the folklore of The Tone Rebellion, the world was literally torn apart in a battle against a dark force called the Leviathan. The aliens who live on these now-separate landmasses suspended in space—the Floaters—have spent eons evolving in their own directions, gaining supernatural, ethereal powers in their exile. Now the time has come for the tribes to emerge from the Great Sleep and reunite to defeat the Leviathan.

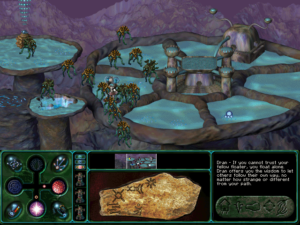

Unlike many strategy games, the key to winning here isn’t about conquering your enemies. Even though you do fight against the minions of the Leviathan and compete with other players over territory, this is a game that’s very much about restoration and renewal, not conquest. You advance through The Tone Rebellion by restoring the broken landmarks that loom over the ruins of the islands you explore. Each time you repair a corner of the world, a piece of mythology from the ancient past of the Floaters is revealed to you; the more stories you collect, the more spiritual strength your tribe gains, allowing you to strike back against the Leviathan and break the seals that give it power.

If you try to play this like a conventional 4X game, you’ll hit a wall quickly. The world has a finite amount of Tone—the mysterious, glowing liquid that provides the life force for the universe. Without Tone, you can’t grow, and with Tone in limited supply, amassing a massive empire is not only impossible but undesirable. The smarter strategy to avoid stretching yourself thin is to keep moving your bases around and leave old territories behind.

You move around the world nomadically, but not with the goal of extracting resources and moving on once they run out, like a cloud of locusts. Instead, you’re trying to make the world whole again. You can fight with other players if you really want to, but ultimately you’re all on the same team. Everyone wants to defeat the Leviathan and reunite their shattered planet; the winner is simply whoever ends with the highest score.

This sounds like a constructive inversion on the usual formula of strategy games, but like a lot of weird games, the more closely you scrutinize The Tone Rebellion, the more normal it gets. While it plays and looks quite differently from other strategy games, it is still a game about resource management, territory control, and building armies to fight your enemies. There’s only so far can that formula can be stretched or reframed before it becomes familiar again—even if you’re working towards shared objectives.

The reason these similarities are so obvious is that, unfortunately, The Tone Rebellion also has some serious issues with the fundamentals of the strategy game genre. We’re talking about some basic quality-of-life things that most real-time strategy games had figured out through trial-and-error by this point, like ensuring that your units actually arrive at their destination when you order them around, or providing some kind of feedback through the game interface to let you know when important in-game events have happened. The pacing is all over the place, at times frantic and at other times resembling the dying turns of a game of Monopoly, where you’re waiting for it to end rather than actually playing it.

This was not the first game by developers The Logic Factory, or even the first strategy game they made, so it’s surprising how poor some of the basics are. It breaks my heart that this is just not an enjoyable strategy game to play most of the time because of problems that are so ordinary.

So instead, let’s focus on what’s not ordinary. Because as much as The Tone Rebellion misses the mark as a robust strategy game, its execution is still singularly weird and fascinating. I can’t think of another strategy game (especially from this era) that puts its lore front and center like this, not just as flavor but as an integral piece of how you play it.

Maybe the title of the game primed me for this comparison, but The Tone Rebellion really does evoke a tone poem. The soundtrack for The Tone Rebellion is broken up into “acts,” according to the filenames of the music, and it does feel like you’re progressing through a grand work of art based on an underlying text you have never read. The game is rich with allusions and portents that it never attempts to neatly tie together. Each piece of the broken world is dense with its own stories, images, and symbols, like a battered highway, weaving through the melted, muddy remains of what appear to be buildings. So much of the meaning and motivation in this game is conveyed through mood, or through suggestion.

Early in my first playthrough of The Tone Rebellion, for instance, when I found an artifact called the Octojen, the game offered me this piece of lore:

The left hand of Mantu forever holds the Octojen.

This is borderline nonsense, like the opening of Kubla Khan written in a made-up language. But only a few minutes later, I came across an orange, rocky landscape with two massive arms jutting out of the ground. These are the arms of Mantu, the game explains, an ancient warrior who stood between armies that would have destroyed the world.

I can’t explain it, but in that moment, it just made sense that the Octojen had to go back in Mantu’s hands. Yes, this was obviously something I needed to complete in order to progress through the game, but intuitively, there was a deeper meaning to it, like you were putting the final punctuation mark on a myth that had been unfinished for thousands of years. Like you were finally allowing Mantu to rest.

The purposely vague mythos of The Tone Rebellion gives even the most basic bits of strategy gameplay more weight and import than they probably should have. In the early phase of the game, when you’re first building your bases and hatching your Floaters, and the music slowly trickles in, it comes across like an awakening rather than the boring procedural part of every strategy game that happens before you get to do any of the fun stuff. That makes an enormous difference. Arguably it carries the game.

And while I don’t want to second-guess something unexplainably magical like this, over and over I had the nagging feeling that everything here could have amounted to something more complete. So many concepts—like a multi-dimensional elemental combat system that changes with the tides of time—needed a second or even third pass to really gel. This is a game with many ideas, not all of which work, or connect, or even make sense in proximity to each other.

Maybe the reason the folklore of The Tone Rebellion so interesting is because it feels pulled out of the pages of some other, completed book. By design, we never get the full picture, like we’re doing our own archaeology of this world in real time. It’s only when that gets put in context that you notice the disconnect between the epic alien legend it keeps alluding to and the half-formed strategy game it actually delivers from that.

There is a brilliant, mystical game buried in here. On its surface, The Tone Rebellion is more just evocative and confusing, which is compelling in its own right.

This sounds so fascinating and I guess I should give it a shot even if some of the basic components don’t really come together. Also just really happy to see a new post on here!

I’m not good for strategy games, but I am a sucker for weird mysterious settings and lore.

So so glad to read back from the Obscuritory ! You let slip a little mistake here:

> Yes, this was obviously something I needed to complete~~ly~~ in order to progress through the game

Whoops, thanks!

Excellent, Obscuritory has a new article!

Glad to read you again!

Hey, you’re back! 😀

Shame about the quality of its gameplay, because The Tone Rebellion is exactly the kind of artsy science-fantasy-adjacent strangeness that appeals to me.

Yeah! you’re back

Is there a reason why your site loads so slowly?

Also some icons seem to be missing (mobile).

Arcade video game or pc video game

I’m playing this game right now on a XP machine, from the original CD I got for Christmas way, way back. It holds up! I like the prioritization and resource constraints; I’ve never tried the multiplayer but I bet it shines there as you’d be racing against other players and so your strategy would become more important.

Thanks for the review! Shame the Logic Factot only produced a few games.