Crime City

Taking a break from his criminal investigation, Steven White visits his girlfriend.

“What’s on your mind?” she asks.

“Do you want to go out for a drink tomorrow night?”

“Ok. I will meet you in the pub tomorrow night at 7 o’clock and don’t be late.”

Steven ends his investigation early the next day to meet her at the bar. 7PM comes and goes; she never shows up. She’s still waiting at home, totally oblivious to the date. This isn’t part of the mystery. The game just forgot.

The dissonance of that moment represents the great dilemma of Crime City, a murder procedural unstuck in time. Time’s urgency and irreversibility are central to the game’s narrative and structure, but it fails to understand the significance of those notions in the places where they matter. Deaf to its thematic strengths and mediocre as a result, it disappoints more deeply than a less potent game might.

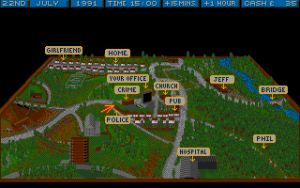

Crime City focuses on the two-months aftermath of the murder of David Walker, a local tired police officer. Authorities pinned the crime on Henry White, his ex-partner turned a private detective. You play as Henry’s son Steven, who assumes the family investigation business in an attempt to prove his father’s innocence. The game opens on July 3rd; you have until the end of August to exonerate your father using any of the tools and techniques he left behind – or by calling for help from anyone in your extended support network.

A standard murder mystery investigation follows, but Crime City constrains you with time. Nearly every action costs some time. If you travel to the far side of town to look for a clue, it might take you up to two hours. Surveillance on a suspect could last all day. The world’s clock is always running, and you need to budget time-dependent activities with sleep. Sometimes you’ll hit a dead end and just have to wait for something to transpire.

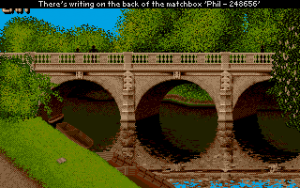

At its start, Crime City suggests some greater thematic resonance from this setup. Time inevitably lurches forward, even as you struggle to keep it within control. Your father’s landlord can temporarily cover your office’s rent given the extreme circumstances, but his sympathy and patience will eventually run out. Suspects turn up dead mid-investigation, as unceremoniously announced by a newspaper that crosses your desk in the morning. Time brings change, and change brings uncertainty. When your lifeline for clues is an itinerant barfly, uncertainty and a deadline are real, present fears.

The first ten minutes – discovering the world, learning your options, connecting with your family, and watching the day slip by as you get your bearings – are exquisite. For a moment, Crime City feels like a study in transience, where your yearning for truth is at odds with a world in flux.

But the game reveals quickly that it has no interest in these ideas. Charades will do instead. Sure, the world changes over time, but changes outside the story are largely restricted to locations opening or closing throughout the day. Almost no actions require a specific time to perform, and the city feels inert as a result. Once you’ve explored every location once, you have no reason to return to any apart from finding the next single clue that drives the story. Any alterations to the world flagrantly signal a new plot development, robbing the setting of potential richness and ruining the mystery’s intrigue.

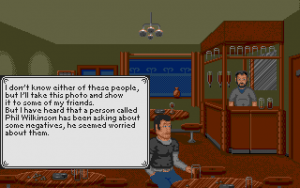

Beyond thematic betrayal, the stagnancy is also confusing. Midway into the game, criminals tied to the murder conspiracy assault you in an alley and warn you not to investigate any further. You can’t inform police about this, though, because they aren’t the next stop in the linear narrative; you have to visit your mother and tell her instead. Later, you ask your girlfriend to investigate an out-of-town source, which she says may take several days. Future communications with her do not indicate that you ever requested her help, leading to a tense waiting period to see if the game remembered your actions. In another case, you can borrow money from one of your contacts, but they’ll never recall the payment-coercing threats they made.

The game dwells on the passage of time, but it shelters itself from the impact of its own themes.

Some inventiveness does emerge from the fixation. The portions of the game where you wait for change are at times delicious: receiving new mail after several wasted days is a reminder about impatience and the cruel ways time can force us to rush or to slow down against our interests. Unfortunately, these downtime segments make up a majority of the game once you’ve seen how little interest the unchanging city deserves. Similarly, the third-act girlfriend fridging for shock value is hacky, but at least it shows a willingness to let the world fracture while the clock ticks.

The rest of Crime City only hints at the more meaningful crime story waiting to be told. As mentioned, the game requires you to sleep to stay alert, but you will never reach a state of deprivation that demands better time management. Money is another limited, time-constricted resource that can be gained or lost through the in-game stock market, but finances are a chore to handle and mostly irrelevant. Crime City sees time as a fleeting commodity and bakes that notion into its systems, but as with the setting, it struggles to leverage that in service of the theme.

(The general writing quality deserves less courtesy appreciation. Most dialogue reads like a breathless, unpunctuated message forum post, sometimes switching perspective and tense mid-paragraph to baffling effect.)

The game wants to say something about irrevocability and finite time, but it takes place in a city immune to the pressures it expects players to experience. Time’s permanence informs every corner of Crime City‘s design, though its often poor and selective application limits the effectiveness of those ideas. This is an opportunity for a poignant crime thriller squandered. Like Walker’s murder, we can’t roll back time to fix that.