Revisiting Liryl in Lighthouse: The Dark Being

As a little break, I recently replayed Sierra’s Lighthouse: The Dark Being. I wrote about this game five years ago and generally enjoyed it, considering how much it lifts almost directly from Myst. Returning to Lighthouse helped me appreciate its tweaks to that template. Between the wall-to-wall machine puzzles, the game finds space to imbue the world with purpose and let players to run off the rails and find their way back. (I’ve updated the original article a bit to reflect my growing fondness.)

More than anything else, though, we need to talk about Liryl.

The character Liryl, the young “sacred ward” of the Temple of the Ancient Machines, stood out in previous playthroughs, but not until this most recent pass did she seem so fascinating, pivotal, show-stopping, and likely divisive. She is the game’s emotional backbone, a devastating central figure who moves the narrative deeper than its stated search-and-rescue mission. She’s also a caricatured object who actively disempowers with her pitifulness.

Lighthouse is a good game; Liryl makes it worth more serious consideration.

Most of Lighthouse takes place in an alternate universe where civilization has barely started recovering from a technology-driven apocalypse. The de facto saviors of this desolate, eroded world are the Priests, a group dedicated to building a sustainable future. Liryl joined the Priests at a young age as a storyteller. She learns the history of the old world and saves it for future generations, either retelling it orally or committing it to a digital medium.

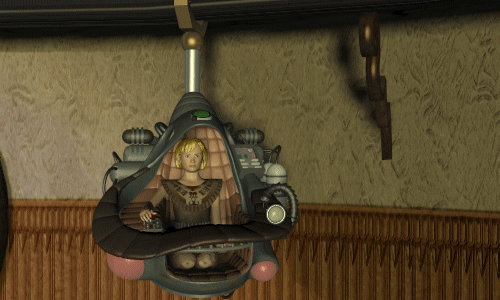

Liryl is also disabled. She alludes to an “accident” in which she lost both her legs and nearly died; the Priests fashioned her a mobility chair that controls her essential body functions – breathing, circulation, and so forth. This didn’t impair her duty to “tell stories,” and she developed a familial relationship with the Priests. In an endearing detail, they would bring her colorful gems and shells, and she would make trinkets from them.

The wise and holy gathered here / Machines of metal cast / They study that which came before / To learn from errors past

When you visit the Temple of the Ancient Machines, Liryl is not doing well. The Priests have been dead for some time. Technology has slowly decayed in their years of absence, with Liryl’s life support in notably bad shape. Her speech is exceptionally strained and filled with electrical glitches. The device will likely fail sometime soon. She cannot leave the temple, and her spirit is ailing. She is alone and suffering, her only confidants have died, and her helplessness leaves her vulnerable to the wrath of the Dark Being. “No pretty stones for Liryl,” she stammers. “Nothing but tears.”

Liryl’s story is heartbreaking, and in a game with few living people, she gives the world a soul. Apart from being a genuinely fascinating character, Liryl’s inclusion in Lighthouse reveals what this world might have been like, who may have lived there, and why it’s worth defeating the Dark Being. Your investment in the game rests not on saving Dr. Jeremiah Krick and his daughter but on whether you take interest in Liryl’s experiences.

But for all this, Liryl is a prop. Confined to a chair and slowly dying, she lacks any agency. Things happen, and she reacts in agony. Her life imbues the world with meaning, but she exists solely for that purpose. Her plight matters only for dramatic effect. She is completely powerless. Her misery feels almost comically overwrought, like a collage of tragic stereotypes wrung for maximum pathos. That’s not terrific, especially for a rare central female character with a disability.

Liryl’s emotional richness indulges in the worst, most manipulative clichés. So what can we make of her? Truth told, I don’t know.

I can’t stop reflecting on Liryl because of how brutal and effective her character is in spite of (or because of?) those damaging tropes. On paper, she reads as a stuttering, lonely amputee in perpetual mourning added to the game for background flavor, certainly a questionable choice. She usually plays more tactfully and interestingly than that. In her first appearance, Liryl speaks about the recovering environment in prose poetry but struggles against her broken machinery to sound out basic words; that offers a sympathetic eye into her life – and reveals more about the world than the game had accomplished up to that point. She’s an arresting character, and the entire game seems to stop whenever she appears.

She has more merit than expected and doesn’t deserve dismissal. But she always threatens to be consumed by the negative stereotypes and weakness suggested by her description. She overcomes that, but I don’t know how closely.

Lighthouse has much to offer in its multidirectional structure and aesthetic accomplishments, but its success hinges on your reception of Liryl. To Lighthouse‘s credit, I didn’t expect that the game would warrant ambiguous, character-driven criticism. This article’s assessment of Liryl may be noncommittal, and that reflects my deep uncertainty over her. At the least, she’s one of the most intriguing, stymieing, and significant characters in recent memory.

I’ve had this game sitting in a box for years now. Might have to give it a go some time. I got a real weakness for the weirdo experimental FMV games from the 90s.

Intriguing. I’d be curious to play and see how I felt about the character.

I hadn’t looked at this game since 1997 until out of the blue today I suddenly thought of Liryl sitting in her mechanical chair! I even remembered her name from 22 years ago when I played the game as a teenager.

Thanks for this great write up on an unforgettable character in a long forgotten game world.

Unfortunately, valiant an effort though the game was (I hadn’t fully realised that it’s technically impossible to get stuck, because there are just SO MANY classic, Sierra-style “gotcha” moments where someone, usually the Birdman, does something that looks indistinguishable from making your game unwinnable…), the ending unfortunately does rather confirm the “hamfisted prop” theory regarding Liryl’s writing.

In the “good” ending where you rescue Krick and Amanda, Liryl, last survivor of her dying world, is nowhere to be seen; nobody even mentions her. Worse, if I recall correctly from the last time I saw this ending, Krick proposes to abandon his teleportation work – leaving Liryl quite possibly the last living sentient being in her entire world, utterly stranded and alone, even though it is now finally and entirely safe, thanks to the player’s efforts, for the genius and benevolent Krick to explore the para-world at his leisure, meet Liryl himself, learn much from each other and possibly even repair her damned chair! It’s actually a pretty horrifying ending after one remember’s Liryl and realises the protagonist and Krick have apparently, somehow, just clean forgotten about her.

I’ve only recently found this game due to the advent of the Let’s Play and GOG, and I think I can safely say there may be one saving grace for Lyril after the end.

A slight spoiler, but when the Birdman is finally subdued, Lyril mentions she intends to fix him to act as a companion for her in the future. So at least the ending may not be as bleak as it looks.

I completely overlooked that Greg; thank you for mentioning that! I may need to update the article.

You know, when I played this game I was kinda thinking of this article, especially during Liryl’s scenes – whilst I feel that yes, it can be seen as emotional blackmail or almost offensive, I felt it was also a hard reminder of why technology *is* needed (as Liryl’s world has discovered), and to stop the game’s ecological themes far away from misanthropic ‘primitivist’ territory – it may have done it in the bluntest way possible, but I feel I could at least understand where it was coming from.

That’s kind of a funny thing, re: the game’s themes – the villainous Dark Being looks all tribal, but he represents the worst of the Industrial Revolution, trying to bring that tendency back to Liryl’s world (reminds me of one JG Ballard story, ‘The Ultimate City’ where residents of a future very similar to the world of Lighthouse, return to an industrial city and attempt to recreate capitalism – I believe the story was collected in ‘Low Flying Aircraft & Other Stories’) and perhaps that was why he also was trying to find a way into our world? I know its vague as to what he was, whether he really is a mythical entity of evil, or just an aged relic of the industrial world gone mad – I prefer that sort of vagueness over direct explanations though.

*to keep the game’s ecological themes, apologies for the typo