Below the Root

Below the Root is based on a series of children’s fantasy novels by Zilpha Keatley Snyder, and without having read the books, I can’t speak to it as a literary adaptation. What I can say is that the game, co-designed by Snyder, is clearly drawing on rich source material, and the Green-Sky Trilogy is a perfect setting for a game with lots of exploration.

In the world of Green-Sky, the people live up in the trees, in harmony with nature. Relevant to the game, the people in Green-Sky wear these cape-like garments called “shubas” that they use to glide through the air, which are very fun to control. As fun as it is to glide through the treetops, though, the thing that makes Below the Root greater than its parts is how pleasant it is, and how it puts kindness, peace, and connectedness at the forefront.

The game picks up the story of Green-Sky where the novels left off. At the end of the third book, the estranged races of the Erdling and the Kindar had reunited, bringing peace to the land. But now, one of the Erdling elders has seen a vision of doom coming to Green-Sky, and they need a new hero to save the world. The trouble is that they’re not quite sure what that vision means or what to do about it. There is no physical evil threat to confront – not that you would confront them anyway since the people of Green-Sky don’t believe in violence. Instead, for your quest, you need to find the spiritual leaders of Green-Sky, who can teach you new spirit powers and guide you about where to look next.

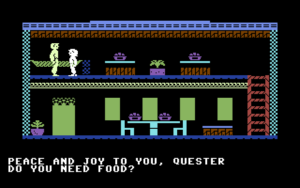

This quest is yours to take alone, but not without aid. You need food, rest, and supplies, and you’ll often have to rely on the kindness of strangers for a place to sleep or a decent meal. All the while, the factions of Nekom and Salite are spreading disharmony through the land, and they’ve offered a handsome bounty to the more impressionable denizens of Green-Sky to turn you in.

If it’s unclear what you’re actually supposed to do, that seems to be by design. Like other big open-ended games at the time, the lack of direction in Below the Root can be intimidating. The developers seem to have expected that you’d need help, so the original release of Below the Root included a paper map of the forest that you could write on as you explored the world. If you’re playing the game decades later, you’re more likely gonna use one of the walkthroughs or maps that are available online. Same idea.

Whatever help you’re using, it takes a few false starts to get your bearings. Once you find the Wise Child of the Garden Grund – the first a-ha moment in the game – the world quickly opens up. She sends you to see the hermit who lives on the top of the Grand Grund tree, who will grant you a new power and give you a clue to your next destination, and so on. You climb across the dense limbs of trees and up and down the ladders on their enormous trunks in search of the item or the person you need.

(The game loosely fits into a subgenre that’s now often described as a “Metroidvania” game, in which you gradually unlock new areas in open-ended game world by collecting items and abilities. That doesn’t quite describe Below the Root, but that’s not an inaccurate way to approach it.)

Below the Root is both forgiving and demanding. It gives you a generous 50 in-game days to save Green-Sky, allowing you plenty of time to explore and get lost. At the same time, it demands precise movement through the treetops, punishing you with a long fall to the bottom if you take a wrong step. Characters with weaker fortitude will need ample food and rest, to the extent that the manual for Below the Root recommends that you scout for reliable safe places to rest in before you actually embark on your adventure. Learning how to survive can be tedious work. But true to the stories, you can never die, only exhaust yourself and wind up back home, ready to start again the next day. Any item you lose can be found again somewhere else. The game never leaves you afraid that you’ll be trapped. It lets you fall out of the canopy, then picks you back up.

This game is cozy and kind in a way that’s surprising for the size of the world, and it truly does capture the mood of a children’s fantasy novel. The houses built by the Erdling and Kindar are filled with furniture and knick-knacks, and when you enter their homes, the screen shrinks a little to convey their claustrophobic, lived-in quality. Every screen in Below the Root radiates warmth, as if someone has been living there for generations before you.

The people matter in this world. A big element of Below the Root is “pensing,” a spiritual power that allows you read the emotions of a person near you. You pense with strangers to find out whether you can trust them, and rather than simply being good or evil, they’re complicated. They could be feeling compassion, avarice, guile, or sympathy, or most worrying of all, they could simply be resigned to their fates. If you do trust them, you still have to ask their permission before you’re allowed to take anything from their house. It’s not that these interactions are functionally complex or challenging, but the fact that they center on trust and emotional intelligence (and being exceedingly polite) sets a compassionate tone for the game.

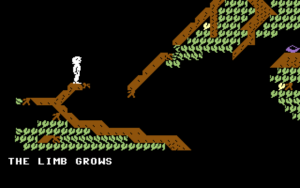

Then there are animals, like the lapans, the bunny creatures that live on the ends of branches high in the trees, who deepen your spiritual power if you go all the way out to pense with them. And the powers you learn from the Green-Sky elders aren’t for combat; you learn peaceful skills that bring you in touch with nature, like “grunspreke,” the ability to commune with trees to get them to grow faster. Presumably, those ideas come from the novels, and they’re unexpectedly charming to see translated into a game genre that was still very action-oriented in 1984. Think about it: one of the major abilities in this game is growing plants! The game is sprinkled with lovely, unassuming moments like this.

Those moments make Below the Root more meaningful than just a platforming game where you forage for berries in an enormous tree, although that’s a good reason to play it too. Below the Root grounds the adventure in trust, literal and spiritual growth rather than destruction, stepping out of your comfort zone to take part in something bigger than yourself.

Further reading

For more about Below the Root, read this personal reflection by Justin Stahlman, who recounts his own experiences with the game, first as a child and then as an adult trying to learn more about its development. Stahlman also compiled a high-resolution map of the game world, which is extremely useful for playing the game today.

The whole layout and graphics very much remind me of Alice in Wonderland, for the Apple II.

Francois: not a coincidence. BtR and AiW were produced by the same company (Telarium, under their “Windham Classics” book-adaptation line), using the same underlying engine. Interestingly, while Below the Root has a wide-open solution path (there’s very little with regard to a mandated hierarchy of things to be done, and a lot of optional things to do which make the quest easier), Alice in Wonderland has a pretty narrow, linear “main route” whose optional subquests are essentially pointless from a point of view of solving the main story.

Alice in Wonderland came later and as such is a more technically adept game (a wider range of character statuses, communication types, and object descriptions), but Below the Root feels more satisfying as a gameworld.

How can I play Below the Root on a computer nowadays? It was my absolute favorite game as a child.