Dominus

Dominus grants you a bird’s-eye view of a swirling battle that spans across a countryside. It also lets you peek into individual houses.

Despite that wildly varying scope, Dominus keeps its pieces simple. The game mines most of its strategy just from shuffling armies around its map. The big hangup isn’t the degree of complexity but the lack of time for everything else. There are so many ways to play Dominus, and with the clock always ticking, an effective playstyle expects you to ditch the more fun, peculiar options.

The game puts you in the shoes of the Overlord, the guardian of a powerful walled kingdom. Eight warring clans on the outskirts of your territory want to take the domain for themselves and have begun storming the gates. With access to all the kingdom’s resources, you can repel the invaders with a combination of military might and intelligence. Victory means stopping the armies from conquering your hilltop castle by wiping them out or coaxing their surrender.

You wage war through a roundtable of generals, each of whom controls a quarter of your army. The generals can commit troops to a number of missions, including spying on the clans for their weaknesses and foraging for supplies. But you’ll send most right into combat. Your map shows how intensely enemies are clustered on each plot of your kingdom; you’ll usually fare better if you wait for them to spread out from their initial invasion and funnel through your streets, though you cede the edges of the map that way. When working through the generals, your main concern is high-level resource allocation instead ordering individual monsters, though you’ll still feel compelled to micromanage each general to eke the most out of your limited muscle.

The game also expects you to control the battle directly, a considerable timesink at odds with Dominus‘s otherwise broadly scoped, managerial multitasking. Zooming into plot of land gives you the ability to cast spells against enemies, finer control over where to summon monsters, and a worst-case-scenario option to enter the battle yourself. These features make lots of sense if you need to defend or recapture critical village territory – or in a tense final stand against invaders as they worm their way to the top floor of your castle.

Normally, though, the effort and energy needed to run a battle yourself rarely justifies the results when you could leave it to the generals. This is especially true for spells. While magic looks extremely cool, you can spend your attention much more efficiently than tormenting specific soldiers with fire or earthquakes in a multi-front, Dominus-sized war. Really most singular actions, like manually crafting a spell, fail to make a noticeable dent in either the conflict or your resources and feel lost in the game’s scale.

Part of the problem may be the lack of transparent information about what could make an impact. Monsters vary in their strengths, like affinity for magic, so deploying them strategically against certain clans can change the direction of battle. However, information about clans and monsters are kept on separate screens, you can’t access any of it quickly in the middle of combat, and the game never clarifies which generals control which troops. Unless you commit all that to memory, you often go into battle blind.

If Dominus‘s combat lacks context, the game’s traps and interrogation gleefully make up the deficit.

With the supplies your armies gather, you can build contraptions to booby-trap your kingdom. Their individual components actually matter here: foliage camouflage works better outdoors, or you might want to capture an enemy with a net payload rather than kill them with explosives. Placing them one at a time in battle is still time-consuming, but the clear differences between a crossbow-loaded treasure chest and a magic-detecting acid trap inform rather than confuse your actions.

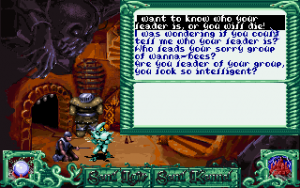

The real fun starts once you capture an enemy. You can bring them into your interrogation room – really just a torture dungeon, if we’re being honest – and prod them for their clan’s weaknesses. Each soldier has their own psychological profile, so while one might lock up and insult you, another could be fearful and respond well to kindness. If you can get them to spill secrets about their clan leader or what types of objects attract them, you can manipulate them in battle or negotiation. If all else fails, you can restock your army with them, playing off their known hatred for other clans to give you a boost.

If you want to be especially cruel, you can also use magic to merge your prisoners and other monsters into a custom nameable super-beast that combines all their qualities. Their uniqueness help you remember their combat traits, and frankly, it’s quality, nasty body horror.

Traps and torture feel more fruitful because they lead directly to new strategies, and their separate components mean something. But still, as with direct control of battle, these features capture your focus, and Dominus seems to not want you to get too sucked into them. The game constantly alerts you to troop movements and other activities, reminding you that the battle outside hasn’t stopped.

Dominus finds plenty of neat dimensions on which you can protect your kingdom – from a broad overview to grilling your prisoners or taking up arms yourself. (Hopefully this is the only time I’ll describe torture as “neat.”) The game wants you to keep your eyes on all of them at once, so out of necessity, everything falls by the wayside except the most efficient strategy through the generals.

When you start Dominus, the clans attack almost immediately, leaving no time to assign troops to gather supplies or check what you already have. You have to tend to combat right away, and the opportunity to settle in and play with all your other tools never arrives. If only you could spend a little more time making magic.

Your website is amazing! I discovered it just now and good lord this is superb! Gives me all the feelings and experiences I had when these games were at the height of their popularity and use. Thank you very much!