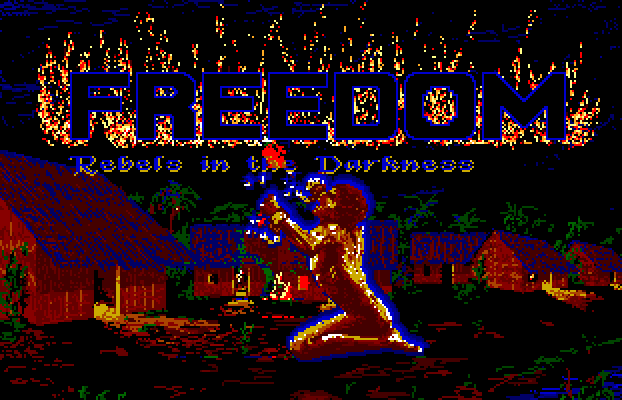

Freedom: Rebels in the Darkness

The world continues to grapple with the aftermath of the Western slave trade. As a society, we still often don’t know how to discuss or even acknowledge the West’s deep history of racial oppression. We intermittently sort through this dark period of history through art both reflective and aggrieved. Despite the wealth of literature and visual media tackling the legacy of institutionalized racism – particularly in America but also elsewhere touched by slavery – games have deferred from addressing race more than any medium; the gaming world’s well-publicized dismissiveness towards diversity concerns makes it generally inhospitable to socially charged, historically conscious work.

In these circumstances, the existence of Freedom: Rebels in the Darkness – a slave rebellion strategy game from 1988 by Afro-Caribbean developer Muriel Tramis – is a miracle. It challenges culture and history on multiple levels, as a cathartic release over centuries of ingrained prejudice; as a retelling of the slavery narrative; and as a classic game that dismantles homogeneous understandings of gaming history simply by existing.

Muriel Tramis designed games for French developer Coktel Vision through the 80s and 90s. Although best known for her contributions to adventure games like The Bizarre Adventures of Woodruff and the Schnibble and Gobliiins series, Tramis’s earlier games are more provocative, often dealing explicitly with race and sexuality at a time when few games approached either subject. As blunt as games like Emmanuelle: A Game of Eroticism may have been, her work shows an interest in themes still ripe for exploration in an interactive medium.

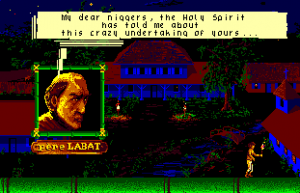

Freedom (alternatively subtitled The Shadow Warriors, or les Guerriers de l’Ombre in French) is, even by Tramis’s standard, one of her most interesting games. Set in her home island of Martinique, the game chronicles an attempted slave overthrow of an 18th-century French plantation. You play as one of four slaves, men and women with different skills, who leads the charge against the plantation owners. A direct violent confrontation would end poorly, so your strategy relies sneaking through the plantation in the dead of night to muster support from other slaves reluctant to join the fight or flee. Watchdogs roam the estate and injury you or alert guards. Once you’ve amassed support, your rattling builds to outright war.

Conceptually, I can’t think of a single other game even close to as incendiary as Freedom. Slavery has only recently become an approachable gaming topic with the development of independent titles like Thralled. But where much slavery media aims for education and humanity, Freedom wants blood. You kidnap slave drivers and set fire to their buildings. Freedom still shocks today, and that it debuted the same year as Super Mario Bros. 2 is almost unfathomable in the traditional framework of game history and culture. (At panels and discussions I’ve participated in, the game always draws audible gasps.)

Freedom‘s historical context matters. It’s a statement from a developer whose background and experiences the industry typically excludes. Tramis’s choice of setting makes clear that Freedom is personal, and the game would not have been possible without the diversity of perspective Tramis and her collaborators (including Martinican author Patrick Chamoiseau) brought to the medium. In an interview from Tristan Donovan’s terrific Replay: The History of Video Games, Tramis testifies to the personal and historical importance of what she made:

“Fugitive slaves, my ancestors, were true warriors that I had to pay tribute to,” she said. “At the time I made the game, these stories were not known. It was my duty to remember. A journalist wrote that this game was as important as Little Big Man has been in film for the culture of American Indians. I was flattered.”

That reflection on history plays a key role in Freedom‘s appeal as well. Apart from perhaps Amistad and the exaggerations of Django Unchained, popular art rarely touches on slave rebellion – or for that matter any account of French slavery in the Americas. While more in-depth and true-to-life stories surely await to be told on those topics, Tramis reveals them in Freedom just by recognizing that they happened. Remnants of African culture like witch doctors and rhythmic music appear as strengths, not novelties. Her inclusion of enslaved women in leading, equal roles in the revolt again opens an oft-ignored corner of history; as player characters, those women are unignorable.

But Freedom doesn’t necessarily need that specific history to be valid or to work as effectively as it does. The game serves as a massive exhale, an airing of generations of anger over inequitable racial and gender power dynamics. And importantly, it’s not a revenge fantasy bloodbath; you spend much of the game spurned by other slaves and slowly cutting through their cynicism and reluctance to risk their families. You triumph not merely through violence but by mobilizing society and correcting an imbalance of power. Freedom remains a visceral game beyond the shock of its concept in how it legitimizes those frustrations and gives them an outlet where, for once, the right side of humanity can win early and decisively. This is an emotional response to slavery, one sprung from the heart of a developer invested in ideas neglected by culture at-large.

I chose to discuss Freedom in cultural context because, solely on its merits as a strategy game, it tends to play clumsily and wields too many concepts at once with too cumbersome of controls. Confrontations with slave masters, for example, are staged as miniature fighting game segments that flow too awkwardly. This likely contributed to the game’s lack of attention (apart from the journalist mentioned earlier), as the few gaming publications that discussed it judged it most heavily on its gameplay shortcomings. I wish the game had been more robust to make it an easier recommendation. As it stands, it triumphs on other terms, primarily its striking angle on a sidelined chapter of history and its counterpoint to diversity-blind declarations of what games have been and can be.

At a time when the treatment of women and people of color in media has come under heavy scrutiny, we need to celebrate Tramis’s success in telling stories of slavery in a medium less attuned to the importance of those stories. Socially powerful, excoriating games have always existed, and there’s a 25-year-old game about African slave women felling their owners to prove it.

For more about Muriel Tramis’s games and career, read The Obscuritory’s interview with the developer.

(This article was lightly revised on August 1, 2018.)

“Freedom is, by a considerable margin, Tramis’s most interesting game.” – I don’t understand why you’re disparaging her other work.

That probably wasn’t a great way to phrase it, and I’ve revised it a little bit. I didn’t mean that to be a slight to her other games; her other work is absolutely interesting, but I think Freedom is exceptional and a standout.

[comment edited on 5/21/20]