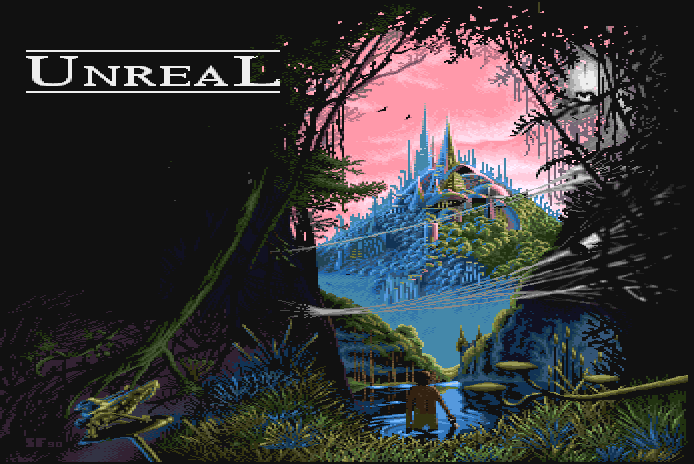

Unreal

To really play the epic Amiga game Unreal, you have to approach it like you were playing it back in 1990.

Unreal – unrelated to the game engine, which debuted eight years later – switches back and forth between two different game modes. For the first part, you fly on the back of a dragon, soaring through prehistoric fantasy landscapes. Then the game swaps over to an on-foot section, and you fight your way through the marshes and mountains, armed with a sword that can absorb the powers of the elements like fire and water. The game cuts back and forth between these segments until you reach the castle at the end and finally confront the forces of darkness that are plaguing the kingdom.

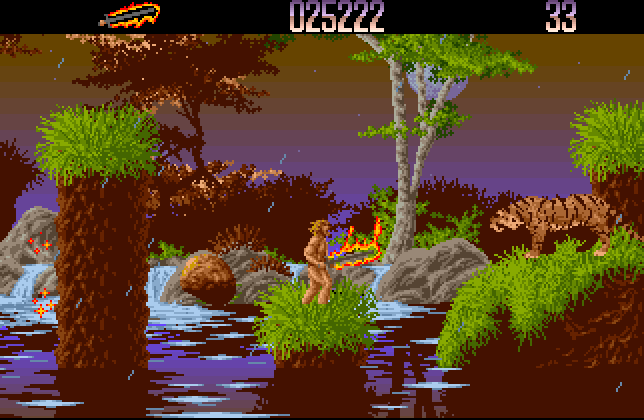

All things considered, it’s a fairly straightforward fantasy game, but for 1990, something like this was pretty ambitious. It’s not just that Unreal jumps between game modes, but the game is also a technical accomplishment for the time. The on-foot sections have complicated, uneven terrain that scrolls in multiple directions simultaneously, but it still runs smoothly, even with animated fire and weather effects.

It’s tough to see in still images, but the flying levels in Unreal really do feel like 3D motion, however limited

The real standouts, though, are the flight levels. They use a simulated 3D effect, where flat graphics are moved around the screen at different sizes to convey a sense of 3D movement. It looks primitive today, but it could be used to render whatever scene the developers wanted, from the inside of a cavern to a river running through a forest.

This wasn’t an uncommon technique in 1990. Sega used it in some of their most well-known arcade games from the late 80s, like Space Harrier and After Burner. But those were full-sized arcade machines that could afford to use more expensive, powerful hardware. If you look at the home computer ports of those games, they had to make significant visual compromises. Meanwhile, Unreal ran with no problem on a plain-old Amiga. The fact that the game was able to pull off these pseudo-3D effects on an ordinary computer was no small feat!

If you read the press coverage for Unreal, the critics who played it at the time focused overwhelmingly on the game’s graphics. Amiga Action proclaimed it “a graphical masterpiece” and “the best thing to come out of UBI Soft.”1 (Yes, this was one of the earlier games published by Ubisoft!) Advanced Computer Entertainment was awed by the speed of the 3D flight sections and, in particular, the “superbly detailed” side-scrolling segments. “You will be drooling each time a new screen appears,” they said with a straight face, “they’re that good.”2

Inevitably, nearly every magazine that covered Unreal compared it to Shadow of the Beast,1,2,3,4,5,6 an Amiga game from 1989 that set the standard for the sort of graphically intensive, technically accomplished, cumbersome games that would define the platform. Every other fantasy action game at the time had to live up to the impact that Shadow of the Beast had, and for game critics in 1990, Unreal came close, maybe even surpassing it. It might have been less showy than Beast, they said, but it was more detailed and vibrant.2,4 In the words of one magazine, it was “the game Shadow of the Beast should have been.”1

Side-scrolling action scenes like this swampland standoff against a tiger are strikingly composed. The magazine Amiga Format called these sections “frequently stunning”7

Can you experience Unreal, as it was intended, without also acknowledging what it was being stacked up against? Playing through the game for the first time now in isolation, the graphics don’t seem as eye-popping as the reviews described – except for the flight sequences, which are clearly running up against the limits of what was possible on the Amiga. Beyond that, the side-scrolling sections are erratically paced and control poorly. There’s a part that stands out in the second level where you need to jump between moving platforms floating on top of a river, and the character moves so awkwardly that I had to repeat it at least one or two dozen times.

It wasn’t until reading some of these historical reviews that I started to think about the game differently. Critics who covered Unreal in 1990 did notice how difficult it can be, but they still heaped praise on it nonetheless.4 The writer for Amiga Format had some of the harshest words for Unreal out of any reviewer, calling it a “plod,” “tedious,” and “a bit thin,” while still having a positive impression of the game overall.7

It’s worth considering that this type of richly illustrated but awkward action game was quickly becoming an institution on the Amiga, and in the context of what else was happening on the platform, Unreal was a strong entry in the genre! With the shortcomings of these games growing more apparent over time as their sheen wears off, it’s not as obvious anymore that they were technical or artistic achievements, so maybe there’s no reason to try judging them by current standards. They’re inseparable from the time – and the platform – they were produced for.

While the parts of Unreal set on-foot are a bit of a relic, the flight sections are still dazzling and epic on their own terms. They’re simpler, and they know when to get out of your way and let the 3D visual effects do the talking. The sight of a massive blocky dinosaur hurtling toward you as you’re soaring across the landscape speaks for itself.

Trivia!

The artwork on the title screen is pretty incredible, but it didn’t originate here! It comes from the 1979 edition of the science fantasy novel Lord of the Spiders, painted by the cover artist Tim White. It also turned up in the game Space Fighter, suggesting that Tim White was open to re-licensing his artwork. (Thanks to English Amiga Board user viddi for noticing the painting in Space Fighter!)

References

1. Steve Kennedy, Alex Simmons, and Doug Johns. (Aug. 1990). Unreal. Amiga Power, 11, p. 74-75. Retrieved from http://amr.abime.net/review_14872

2. Laurence Scotford. (July 1990). Preview: Unreal. ACE: Advanced Computer Entertainment, 34, p. 40. Retrieved from http://amr.abime.net/review_14872

3. David Wilson. (July 1990). Vive La Difference! Unreal. Zero, 9, p. 34-35. Retrieved from http://amr.abime.net/review_39873

4. Ben Mitchell. (Sept. 1990). Unreal. ACE: Advanced Computer Entertainment, 36, p. 53. Retrieved from http://amr.abime.net/review_37794

5. David Wilson. (August 1990). Unreal. Zero, 10, p. 38-39. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/zero-magazine-10/

6. Robert Swan. (August 1990). Review: Unreal. Computer + Video Games, 105, p. 61. Retrieved from http://amr.abime.net/review_12044

7. Rod Lawton. (Oct. 1990). Screenplay: Unreal. Amiga Format, 15, p. 70. Retrieved from http://amr.abime.net/review_2046