Odyssey: The Legend of Nemesis

There’s nothing new to the idea that, in a world overrun with grotesqueries, humans may be the real monsters. Odyssey: The Legend of Nemesis, a role-playing game for the Macintosh, brings a level of specificity and empathy to that concept. Rather than swing into allegory, Odyssey roots its big ideas and moral choices in the lives of individuals.

The game has room to try different permutations of this theme – new people, new troubles, and new ways to end them. Though the confusing attempts to extend that variety to the game’s combat come close to ruining the experience, Odyssey‘s playground of extreme human behavior and its believable writing pair terrifically together.

Odyssey opens as you awaken shipwrecked on the shore of the island of Un. Your voyage to find a magical staff to save your home ended in disaster; not only are you stranded, but your staff ended up in the hands of Nemesis, a seemingly omnipotent mastermind who watches over the island.

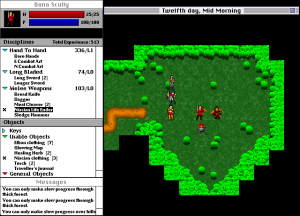

The two towns on this island mirror each other. The people of Elba, healthy from their advanced medicine, wear blue and love food and drink; to the south, Niac wears red and dominates art and the military with a whiff of fascism. Their societies live in mutual hatred, and a handful of people in both towns want to change that relationship.

But as you discover, Un isn’t alone. Nemesis created the island and a half-dozen others as an elaborate experiment on the nature of evil. Each has a peculiar social structure stressed to its limit by the appearance of monsters. The second island, Culn, houses a religious sect; the priests’ attempt to shore up spiritual solidarity against the outside threat led them to enslave their followers in a mine. The path to Nemesis lies at the end of his archipelago, but on your way, you have a responsibility to help these wayward societies.

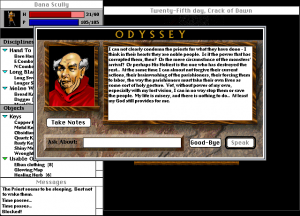

The game frames its scenarios almost as parables about loving your neighbor and appreciating difference. It lacks subtlety – two brotherly cities named after Cain and Abel, really? – yet Odyssey has greater clarity in its writing than the broad strokes suggest. The characters may be players in a larger moral narrative, but they speak with their own voices. (With exceptions, like an incongruous French chef.) The two lovers in Un separated by petty conflict aren’t empty vessels for themes; they have their own fears, wishes, and vulnerabilities, revealed in monologues as they go through their day.

As interesting as it is to figure out how these societies mutated into their evil, dysfunctional forms, the people give the game its weight. Like the Pitor, a kind-hearted if meek survivor of the monsters whose chose to live in solitude rather than fight an unjust ruler. Or Thomas, the Elban artist who sneaks into Niac to hear their music despite the great personal risk. Odyssey balances its attention to individual lives with what they represent, and doing so, it earns your care for both.

The writing is great, to be sure, but much of this achievement can also be pinned to how the game parcels out its stories. Setting Odyssey on a series of islands breaks it into smaller, discrete episodes. Apart from a few clues about Nemesis’s experiments, these are standalone chapters. You can still wander around freely, but you discover the secrets of one island at a time before moving to the next. In contrast with the intimidating, bottomless sprawl of a single open world, there’s less chance of getting totally lost in an optional quest or forgetting what your goal is.

More importantly, this lets the game experiment with a range of tones. The haunting irony of Morage – where the survivors don’t realize the monsters are their loved ones – stands separately from the weirdly hilarious identical towns of Billsville that imprison non-Bills. Odyssey‘s soundtrack of live performance classical piano pieces creates moods for these sections where none exists, like injecting tension into a town scene that would otherwise seem idyllic.

In the best cases, the islands physically embody their themes. The head priest of the Community in Culn, for example, built an elaborate underground tunnel system to protect his order’s secrets. Its aimless, spiraling hallways and doors to nowhere reflect the priest’s fevered state of mind, and they pose a unique challenge compared to dungeons elsewhere in the game. It’s an excellent fusion of character and design.

Just as it experiments within its episodic structure, Odyssey gives the player opportunities to experiment with multiple solutions and playstyles. Many of the islands’ dilemmas have a peaceful and a violent resolution. For instance, you can either free the slaves in Culn by destroying their religious icon or instigate a mass murder of the entire Community. Other islands have multiple plot threads to follow or abandon as you wish: do you give Niac a book of all Elba’s medical secrets, not knowing how it might upend the balance of the cities years down the line? If you want to skip the big crises and just solve the side puzzles called the Vex Chambers, that’s an option too.

Saving and helping people are obviously better goals. But Odyssey doesn’t treat these as moral choices as much as just alternate outcomes. Without a plot barrier, formal judgment, or long-term consequences (apart from maybe getting a cool new weapon), the morally right resolution is the one that satisfies you. That keeps the focus on the people you’re affecting, and it saves the game from falling into the sort of perfunctory tug of war between good and evil that tends to dominate RPGs.

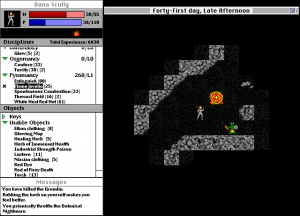

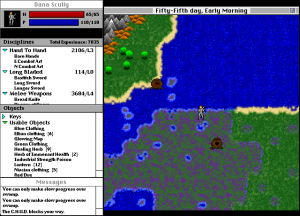

The narrative’s open-ended variety carries over to the game’s role-playing mechanics. Odyssey includes a wide range of tools for defeating monsters, especially the psionic magic powers you can find hidden away in dungeons. Every psionic class has a range of applications, like single bursts of damage or shields or something stranger (like The Collective, which applies a grab bag of enhancements). Beyond the expected fire and ice spells, you can learn powers like aeromancy or luminancy. Combat tends to be too repetitive and highly luck-based (remember to save often!), but the number of options keeps fights fresh in the long-term.

And yet, despite that, Odyssey still accidentally pressures you to play a certain way.

Fighting in dark, narrow caverns (atmospheric as they are) limits how much you can explore the assortment of combat options

The game’s bizarre experience system rewards you additional health and psionic power depending on the weapon class you use. Essentially, it forces variety. Based on how the game spaces out leveling bonuses, it makes the most sense to change weapons and psionics regularly – and to avoid psionics that don’t directly damage monsters. Cycling your equipment through the game’s menus is cumbersome, and every swap costs you a turn or two in battle. Even if your other weapons and powers are far too weak, you have to switch around.

If you don’t, the game’s difficulty increases dramatically around the third island, and you’ll have to stop and turn back to gain experience correctly from flimsier enemies. Most of Odyssey‘s combat takes place underground, which forces you (at least initially) to use one-handed weapons while carrying a torch and almost guarantees that you won’t level up other weapons at the correct rate. Trapped into an optimized playstyle, you really can’t skip around as much as the game wants you to.

In his book Game Design: Theory & Practice (2005), Odyssey‘s designer and writer Richard Rouse III admitted that combat wasn’t his priority, and he included it mainly to meet expectations for the role-playing game genre. “The game’s levels were not designed with exciting battles in mind,” he says, “and combat situations in the game were not as compelling as they could have been” (p. 48). Unfortunately, the same auteur design that gave Rouse tight control of the narrative ensures that his inattention here nearly sabotages the game.

Its strengths instead lie in its writing and characters. In the first Vex Chamber, Nemesis asks you a series of prodding moral questions; at the end, he disregards your answers then cautions that “actions speak louder than words.” That’s what Odyssey is about. Isolated in their peculiar lifestyles, the islands turned dark in their own way and, if Nemesis should be believed, revealed their peoples’ characters more truly than their declared ideals would.

Odyssey looks past platitudes. It tells the stories of people, how their actions destroyed the world, and what impact your actions might have too.

Trivia!

Odyssey uses the same underlying engine as Bungie’s multiplayer game Minotaur: The Labyrinths of Crete, though it appears heavily modified.

According to a retrospective included with Odyssey‘s free release in 2004, Rouse developed a game for the Macintosh partly because games for the platform had lower expectations for advanced graphics and features (and thus a lower barrier for entry) than games for Windows. He kept a “towering pyramid of Mountain Dew cans” that he refused to get rid of until he finished the game.

References

Rouse, R., III. (2005). Game Design: Theory & Practice (2nd ed.). Plano, TX: Wordware Publishing.

Wow I had a demo of this game as a kid and played it over and over. I wish there was some gameplay footage online.

Me too, flashback!

To this day this is still one of my favorite games of all time! What a beautiful story this game has, and a haunting soundtrack too.

Case in point, I go as Wally Hackenslacker in most of my online presence in honor of this game. That was the default player character name.

Loved this game back in the 90’s. Must have run through it a dozen times and made sure to hit every quest. And exploit a bug that let you get two Niacan Life Enders on the first island (can’t use two at once, but it sells for a LOT since it was a quest item weapon)