Tom Clancy’s ruthless.com

It’s almost beyond parody. Tom Clancy’s ruthless.com.

Towards the end of the 90s, Red Storm Entertainment, a game studio founded by nationalistic spy novel purveyor Tom Clancy, made a strategy game about the future of corporate warfare in cyberspace. In the not-too-distant, post-Y2K future, every megacorporation is a software company. If you’re not a business executive, you’re either a hacker, a lawyer, or a hitman.

Obviously, that’s not what happened in the year 2000, and yes, it’s funny to look back at what pop culture got wrong about the future. The reason ruthless.com‘s vision of the cyber-future is so interesting – besides the game’s over-the-top, cyber-industrial theme – is because the game is incredibly vague and evasive on details. You run a company that makes technology. Your chief exports are Ideas and Products. Put that side-by-side with a business game like Capitalism, which breaks down the entire production chain and unit costs for real-world products like cars and laundry detergent, and ruthless.com looks downright abstract by comparison.

For Red Storm Entertainment, this vaguely defined futuristic setting was a great excuse to create a wild, free-ranging war game that loosely resembles what it would be like to run a giant corporation with the power of a nation-state. But the game is vague for a reason! As the title of the game suggests, ruthless.com is inspired by the sense of futurism that came out of the late 90s at the start of the dot-com bubble, an era filled with empty promises about technology and business, a few years before the realities of both would come to pass.

Usually when we think about the tech industry crash from the 2000s, there are a few standout examples of disastrously mismanaged companies that capture the spotlight, like Pets.com, a pet supply retailer that managed to raise millions of dollars, launch on the stock market, and go out of business within just two years. But at least Pets.com had a clear business model: they sold pet supplies. The companies that raise the alarm for me are the banal ones that were briefly worth billions of dollars for no apparent reason.

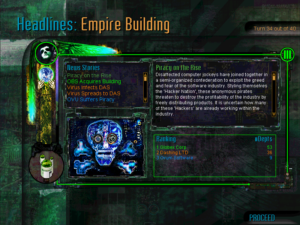

The visual style of ruthless.com is overloaded with the high-octane cyber-nonsense of the late 90s. Each player skin includes its own cyber-motifs and musical fanfares

While I was reading up on the dot-com bubble for this article, I came across a financial book from the year 2000 – The 100 Best Internet Stocks to Own – that’s filled with meaningless business advice like the “jiujistu approach to corporate strategy” that supposedly explains what companies would succeed.1 Surprisingly, the book’s list of the top 100 internet stocks doesn’t actually include many of the hyped-up, high-profile failures from this era, but instead it’s loaded with semi-anonymous companies with cryptic, jargon-laden mission statements. I have no idea what they did, and I’m not sure they did either.

#52 on the list is AppNet, a corporation valued at $681 million at the end of 1999, that “brings the power of eBusiness to companies.” AppNet’s business seemed to revolve around “an aggressive acquisition strategy” to grow its customer base by purchasing other eBusiness companies.2 In other words, they were a big company because they were a big company. The food chain continued when AppNet itself was purchased for $1.4 billion by an even larger eBusiness company called Commerce One3 – which would collapse a few years later when the entire eBusiness sector failed to materialize.4,5

What did AppNet and Commerce One actually do? It’s irrelevant! They were technology, and that was the future, and that was considered valuable enough to sink billions of dollars into owning a bigger share of a market that wasn’t actually proven to exist. They were in the business of being a business.

Tom Clancy’s ruthless.com is like running one of those nondescript billion-dollar tech companies, except much, much more vicious.

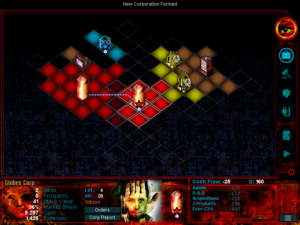

Tom Clancy’s ruthless.com imagines the tech market like a world map, with road-like circuits connecting the “Network” of your business empire

As the head of a new software company, your objective is to control as much of the market as possible and overwhelm your competition. It’s unclear what your company actually does, but the important part is being the one that does it the most.

The market is represented as a tile grid, like the map in a war game. Everything flows out of this metaphor. When you develop new products, your territory grows, and you capture more of the market. If you’re not performing well in a certain area, your marketing department can reposition your product – by literally repositioning your buildings on the map. It’s attempting to translate the language of big business into the format of a conquest-and-diplomacy game like Civilization. The concepts overlap each other fairly well, something that was no doubt aided by years of managers assigning Sun Tzu’s The Art of War as a business textbook.

The supply-and-demand twist in ruthless.com is that the overall size of the market can grow too. As your software empire expands, the map keeps getting bigger, and new startups will pop up when they smell an opportunity to compete on the edges of the developing market.

When a new competitor rears their head in the industry, you can either gobble them up or drive them out of business. If they’re small enough, it might make sense to buy them out early to lap up their revenue and their share of the market. But if buying them is out of the question, the only other option is to crush them under your boot using the full force of a billion-dollar corporation.

This is where ruthless.com earns its name and lives up to the promise on the front cover that “This isn’t business. This is war.” If you can’t drive your competitor out of business through economics alone, you can resort to more extreme tactics, like hacking their network to shut down the company, or blackmailing their executives. If you’re desperate and willing to pay your operatives some hush money, you could even take their CEO hostage or straight-up assassinate them. This is the dot-com bubble as only a Tom Clancy surrogate could imagine it.

On top of it all, there’s the legal system, the most sinister method of corporate subterfuge. If you set up a legal department in your company, you can accrue “Legal Points” that you can spend to bully other corporations into submission with lawsuits. It’s like a second shadow strategy game happening underneath the rest of the game, with all the major companies keeping each other in check through a legal arms race – and, if necessary, spending their points to ward off anti-trust investigations from the Department of Justice.

This sets up a dynamic, unpredictable game of warfare that spans multiple layers. Everyone is fighting for a bigger piece of the market using whatever tools and techniques they have access to. There are so many vectors for dealing with your opponents – legal, marketing, negotiation, human resources, computer sabotage, criminal mischief – that you can accomplish just about any task in multiple ways, depending on the unique strengths your company has grown into. To learn dirt about another corporation, for example, you can hack them, or you can infiltrate their office, or your acquisitions team can do perfectly legal due diligence research on them.

It can be exciting, and often relentless, to fight over not just the map but the other half-dozen invisible power struggles that are also unfolding. When every cylinder is firing, ruthless.com is genuinely exciting, which I didn’t expect going into this kitschy-sounding Tom Clancy game about the dot-com era.

The worst excesses of the tech industry will lead to “Calamities,” like a piracy epidemic caused by too many hackers on corporate payrolls

It’s so much funnier, then, that you’re having this high-stakes espionage battle over a business that’s so vague and meaningless. Like if you sue somebody, it doesn’t even matter what the lawsuit is over, because nobody has any clearly defined products. Concepts like “law” and “computers” are just generic resources to squabble over, like wood and sheep in Settlers of Catan. There are good, understandable reasons why ruthless.com has to simplify these mechanics and leave out the specifics for the sake of a streamlined, playable game, but it’s still weird to run a company that ditches the pretense of being anything but a market grab for its own sake.

Doesn’t that sound a bit similar to how those failed dot-com companies operated? It didn’t matter if nobody understood what they did, as long as they were cornering the market for it. What did it really, practically mean to be a leader in eBusiness, and how was it different than being a leader in eServices – another supposedly real business sector that was mentioned in that internet stocks book?6

At that moment in history, “tech” was both exciting and scary, carrying all the weight of the rapid societal change that was anticipated to come in the new millennium. It’s not clear what “tech” even was, necessarily, but it felt like it would be important (and therefore lucrative), because a company like AppNet or Commerce One could blast off solely on the promise of a digital eBusiness revolution that mostly turned out to be smoke and mirrors.

Tom Clancy’s ruthless.com reflects what this might have looked like from the outside, the notion that technology was an undefineable, almost mystical concept that held the keys to the future, and this new wave of dot-coms and internet companies could profoundly change society as we knew it.

The domain name ruthless.com is currently vacant and can be purchased for $50,000.

References

1. Kyle, Greg A. (2000). The 100 Best Internet Stocks to Own. McGraw-Hill, p 32. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/100bestinternets00greg

2. Kyle, p. 59-60.

3. Commerce One, AppNet tie. (2000, June 20). CNN. Retrieved from https://money.cnn.com/2000/06/20/deals/commerceone/

4. Gilbert, Alorie. (2002, July 16). A second act for Commerce One. CNET. Retrieved from https://www.cnet.com/news/a-second-act-for-commerce-one/

5. Hines, Matt. (2005, Sept. 23). Commerce One melting down. CNET. Retrieved from https://www.cnet.com/news/commerce-one-melting-down/

6. Kyle, p. 18.

I remember you streaming this game a few months back! Interesting read 😀

Thanks for the positive review and good memories. I was lead engr. on this game. Great team.