Eyewitness Virtual Reality Earth Quest

The educational TV show Eyewitness has an instantly memorable opening hook. The show is set in museum – not an ordinary museum, but a building where science and history literally come to life. Animals roam the halls, the exhibits defy gravity, and the computer-generated walls are a perfect, spotless shade of white. Eyewitness was based on a series of informational children’s books by Dorling Kindersley, and while the books had great pictures, on television, learning became a destination.

It makes so much sense to adapt Eyewitness into a computer program. CD-ROM adventure games in the mid-90s were playing with the idea of being physical places you could explore from a first-person perspective, and multimedia software was taking inspiration from that. The Eyewitness museum was a cool visual on the TV show, and now it could be a place you’d actually visit to learn about science.

The intro from the Eyewitness TV show

Dorling Kindersley was mainly a reference book publisher. Their venture into developing CD-ROMs began when Microsoft attempted to take over the company. According to DK co-founder Christopher Davis, Microsoft wanted to get the digital publishing rights to their entire print catalog – in particular, the imaginatively illustrated best-seller The Way Things Work – even if that meant purchasing the company itself.1 In 1991, they bought a £8 million stake in Dorling Kindersley2 and attempted to buy out more from within the company’s board room. DK fought back. They eventually came to a weird arrangement: DK would supply content for Microsoft Home CD-ROM titles like the Encarta encyclopedia and Microsoft Dinosaurs, and Microsoft hung around as “semi-benevolent minority shareholders.”1,3

The antagonistic agreement turned out surprisingly well for Dorling Kindersley. Microsoft’s failed takeover gave DK the resources to start their own multimedia division. Davis called it “a platform for growth.”1 Now DK could adapt their books and encyclopedias for the CD-ROM format by themselves.

That put them in a position to work on ambitious concepts like Stowaway! and Castle Explorer, educational mystery games built around the extraordinary detailed Where’s Waldo-type history illustrations from Stephen Biesty’s Cross-Sections books. The Eyewitness Virtual Reality CD-ROMs were bold, transformative ideas too – using their research library to create interactive virtual museums. But a few of the later Eyewitness titles, like Earth Quest, took the concept a step further, upgrading the simple white museum from the TV show into an extreme museum that could never exist in real life.

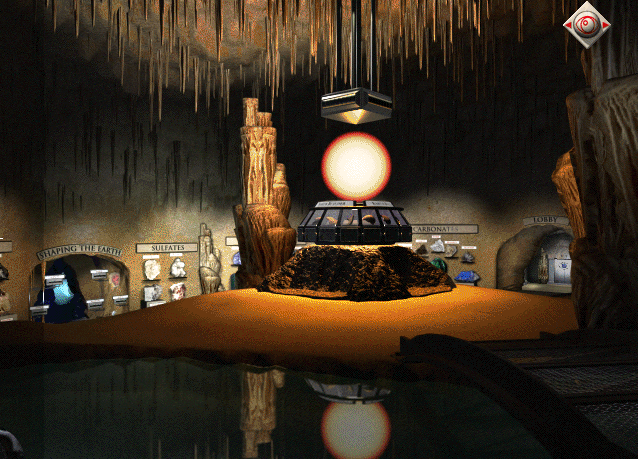

Earth Quest teaches you about earth science, like how minerals are formed and what the tectonic plates are, and the museum is built inside a giant cavern. It feels like you’ve stumbled into an excavation site. The doorways are carved out of stone, and the exhibits about gemstones and ores are built into the rock walls. As you walk around, you can hear water dripping. Where an actual museum might have a famous sculpture or a dinosaur skeleton in the center of the room, this museum has the earth’s core, shrunken-down, sitting on a pedestal and lighting up its surroundings.

Owing to their art experience, all of Dorling Kindersley’s CD-ROMs look terrific, but Earth Quest is especially spectacular. The museum is monumental. Even though it has a small footprint, it thinks in terms of hulking earthworks and geography. There are a few side exhibits, like a Violent Earth pavilion about earthquakes and volcanoes, and they’re presented on the edge of cliffs overlooking giant expanses of the earth. The balcony of the Shaping the Earth exhibit overlooks a view that moves between mountains, deserts, valleys, and islands to illustrate land formation. This is a museum so enormous and grandiose that the planet itself is on display.

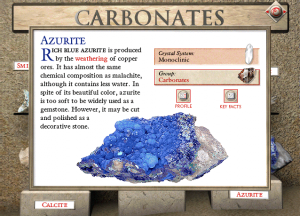

Sometimes, the CD-ROM uses that just as a stunning backdrop. The exhibits in main Earth Gallery room of Earth Quest are static displays, with beautiful close-up photographs of gemstones and rocks, along with descriptions and video clips. They’re well-made but much more engaging because they’re part of this explorable place and they’re inset in a rock wall or pop out of a 10-foot-tall diamond.

The standout parts of the museum – the ones that take the most advantage of this vast, impossible setting – are the interactive exhibits, like that grand overview of landforms in Shaping the Earth. Over in the Violent Earth pavilion, you can simulate an earthquake on a virtual city and see how changing the focus or the epicenter wreaks different levels of carnage. Then when you’re done destroying the city, you can read more about how earthquakes work!

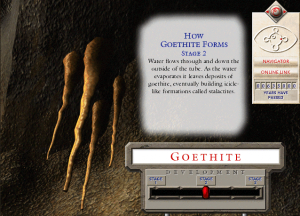

Beyond just the physical expanse of the earth, the interactive elements also help communicate the immense amount of time it takes for geology to change. Time passes quickly in the museum – 5,000 years every second – fast enough that you can see minerals growing on the walls of the cave. The program will alert you when, for instance, aragonite forms after 1,185,000 years. It gives you a good perspective on the long timeline of the earth by putting you there first-hand, although the constant, loud updates about fluorite or sulfur or whatever can be distracting and cause an unnecessary sense of urgency, like getting a flurry of push notifications. (You can at least turn them off and check out Earth Quest on your own time, but they could’ve been less intrusive.)

Tying all these exhibits together, at the center where the core sits, is a scavenger hunt game called Earth Builder, where you rebuild the tectonic plates by answering questions you can learn in the museum. You also have to harvest the minerals growing in the cave, a cool task that connects the different dimensions of Earth Quest in one activity. Earth Builder shares a lot with the scavenger hunts that actual museums give to kids to keep them engaged, and like those games, it offers a helpful guiding structure for your visit if you want to follow it.

Dorling Kindersley packed lots of information into Earth Quest, but not always in a way that’s consistent to navigate or interact with. Sometimes you have to click on the bottom of the screen to back out of a section; other times you have to turn to the sides and walk away. Many of the exhibits have buttons that link you to other related displays elsewhere in the museum, but occasionally they don’t.

Christopher Davis noted how DK’s CD-ROMs would run over their budget and scope because every producer “wanted to add another winning feature, another ‘what if you clicked on that and it opened another dialog box which in turn accessed another window into the library of cyberspace information?'”3 Why not when a 650MB CD-ROM seemed so huge? You can sense that happening here, between the multiple interactive wings of the museum, the Earth Builder game, the geological clock, and the reams of information that didn’t fit anywhere else but got included anyway in a pop-up window.

They also threw in a web-connected feature called Online Link, which is so prominent that it has a dedicated button in the interface. The internet would eventually make reference software like Earth Quest obsolete, and while groups like the CD-ROM publisher The Voyager Company struggled to stay relevant in that transition, Dorling Kindersley seems to have welcomed it as a supplement. Unfortunately, the website was removed within three years of CD-ROM’s release, so we don’t know how DK integrated the two formats – besides setting aside considerable space for it, expecting the internet would be a big deal.

The program can feel oversaturated. The content is top-rate though, and it looks incredible in the setting. Compared to an encyclopedia, placing the material in a heavily themed, hands-on virtual museum that you can explore like an adventure game is novel enough to make it immediately more present and more exciting.

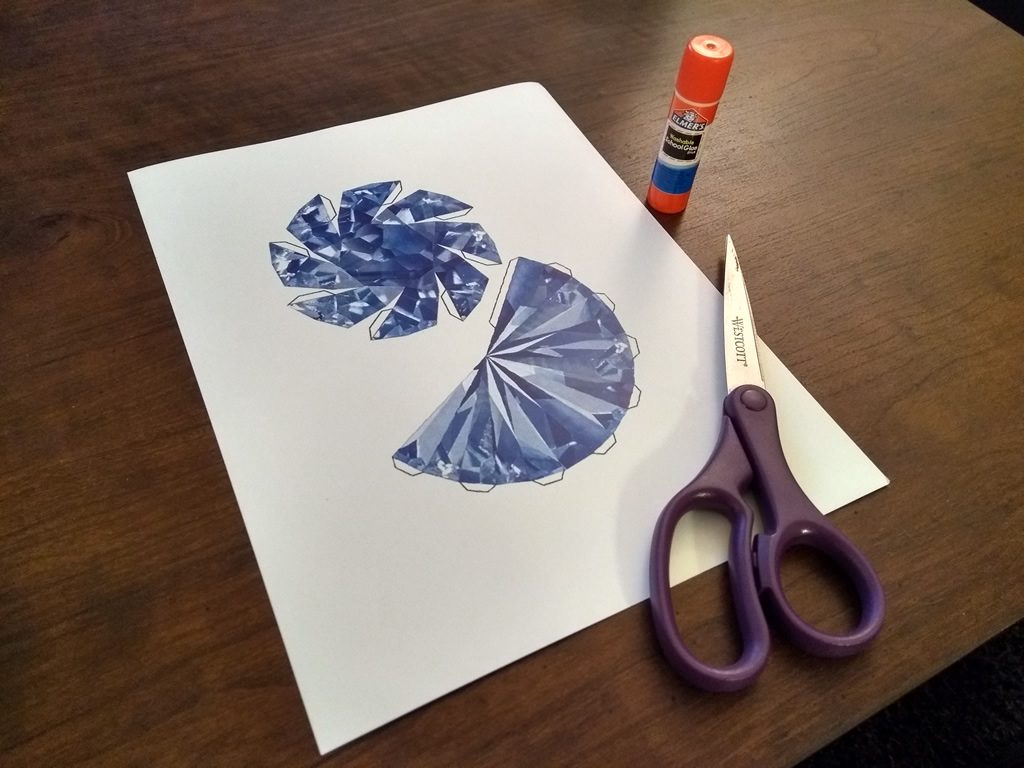

And like any good museum, Earth Quest has a gift shop! All the Eyewitness Virtual Reality titles commit to the museum theme and have a gift store next to the entrance. It’s not a joke either! There are real things to take home with you, like desktop wallpapers and printouts of posters, signs, and even foldable 3D papercraft gems. It’s such a delightful, clever touch. Home office software was an exciting concept in the mid-90s – you could print out your own designs! – and combining that with the idea of virtual multimedia museum is a great snapshot of how one publisher saw the unique, creative possibilities of what you could do with computer software. Dorling Kindersley wanted this to be like a real field trip.

I couldn’t resist. I got a little souvenir for myself. I couldn’t get the top and the bottom to fit perfectly, but it was too much fun to sit down for an hour to put it together.

If you want to print out and assemble your own 3D sapphire, you can grab the template here! This includes both the color printout and a blank outline that you can color yourself.

References

1. Davis, Christopher. (2009, July 1). Eyewitness : The rise and fall of Dorling Kindersley. Petersfield, Great Britain: Harriman House. 160-165. Retrieved from ProQuest eBook Central

2. Shandle, Jack. (1991). The birth of an industry. Electronics, 64(5), 13. Retrieved from ProQuest Central

3. Davis, 218-220.

thanks for this post. I was talking about some educational “games” I had as a child, took me a long time to hunt the name of this one down, could just remember building up the earth in the centre and the crystal cave part. I also had Virtual Safari…highly recommended as a child – both games I got from the PC Ace magazine in the 90’s

I remember this game from my childhood – I loved it so much!

Great article on the game, I loved this when growing up along with other titles such as the “Eyewitness Encyclopedia of Space and the Universe” and Myst. I was curious though as to how you got this to work on a modern machine, I’ve been trying to look all over for a download or a guide on how to make it run on modern hardware but I have yet to find as such, I mean, this is in a bit of obscurity ha. Any help or input on this matter would be greatly appreciated as I would love to show my fiance what I grew up with.

These games were so great, and probably a big reason of why I went on to study biology. Have you ever heard of the Microfolie science encyclopedias, “The Ocean of Origins” and “At the Origins of Man” (translating from French — sadly, they don’t seem to have penetrated much into the English-speaking market). If you’re interested, I’ve put together translated footage of the former here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLcMUlGK34vd0B19TJoHyirJ3vSM5lO5vY

I remember my family had this when I was a kid, along with a huge stack of other Dorling Kindersley games (which we always just referred to as “the DK games”), and this was one that I found a bit confusing. I may have been a bit too young for it at the time. It’s fascinating and a little surreal to read such a thorough article on it almost 20 years later!