Breakout roundup

Breakout is such an obvious idea that it’s weird to think somebody had to invent. The ball-and-paddle game formula is super simple, and countless games have copied it, notably a huge number of older free and shareware games, often by new developers starting out with something less complicated.

It’s difficult to talk about Breakout clones on their own, because they’re all copying from the same well-trodden template. And for the sake of this blog, I didn’t want to write half a dozen short posts about games that are so similar.

So instead, let’s talk about a bunch of them all together! For this article, I wanted to cover a variety of games inspired by Breakout that I’ve been meaning to play and talk about what makes them interesting. These games try to jazz up the ball-and-paddle game genre, either by adding new features or changing something about the genre itself. Maybe we’ll learn something by looking at several different Breakout clones at the same time!

Dragons: A Challenge in Chivalry

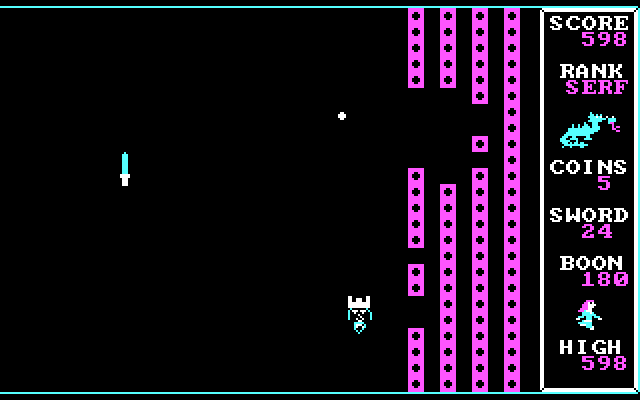

Hark! Dragons by F. A. Willshaw from 1986 puts a slight medieval twist on Breakout. You’re not just breaking bricks; you’re rescuing the Princess Gwen, who has been trapped behind the “multi-walled castles” of the emperor Peter the Nerd, who apparently drew the short straw when picking a royal name.

This really didn’t need a damsel-in-distress brought into it, and the fantasy overlay is pretty silly in places (your ball and paddle are now a “golden coin” and a “magical sword”). The major thematic addition is that Dragons adds adversaries for you to clash with. On each level, there’s an evil knight or a wizard who wanders around creating more walls between you and the princess. Of course, once you hit them with the ball, nothing else exciting happens for the remainder of the stage, leaving you with just a slower version of Breakout with awkward, halting controls. (Dragon handles your controls in the same way that an office program will wait a second after you hold down a key before repeating your input. In a game with lots of movement, that’s not great!)

The best touch is that between levels, you graduate through the feudal system, starting off by earning the title Serf and progressing to the rank of King. If you’re going to put a veneer of wizards and dragons on a generic arcade game template, it may as well be silly like this.

When you clear a level, the entire screen fills with gigantic letters spelling the words “I DUB THEE… SWAIN.” If only real feudal systems were this mobile!

Beebop

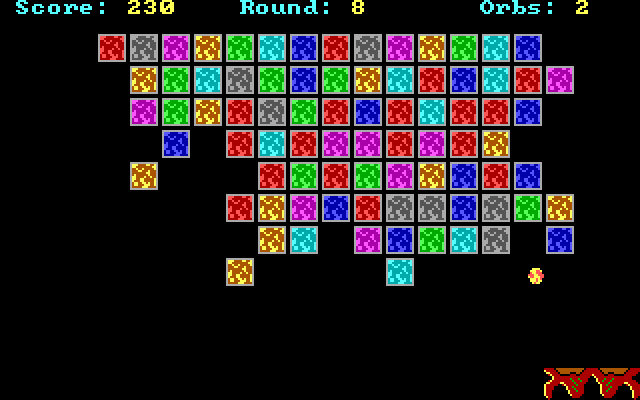

No matter how different they are, just about every Breakout clone has the same objective: clear all the bricks. Some variations on the game might add new obstacles to trip you up, like unbreakable bricks, but there’s always a ball and there’s always a paddle. Beebop for the Macintosh is no different in that respect, but it pushes the template in a new dynamic direction.

Beebop throws out all the rules about how to design Breakout levels. It’s not just that the blocks are arranged in interesting shapes; the game also makes big structural changes to how levels are laid out. There might be a platform under the paddle to prevent the ball from falling down, or the stage might be separated by walls. But the major twist is that while you’re playing Beebop, the stages will change!

Clearing bricks will open up new sections of the levels. This allows the game to play around with unusual designs, like a stage that starts out in tight quarters but gets roomier as you break more bricks. It opens up so many possibilities that I didn’t even realize Breakout was missing until this point. The standard ball-and-paddle layout – with a paddle on the bottom and bricks on the top – feels instantly outdated by comparison, like going back to a silent film after seeing a talkie for the first time.

This is a more intricate version of Breakout, almost clockwork-y, and the reason it works is because Beebop is so tightly assembled. The ball’s movement is much more predictable: hitting the left side of the paddle makes the ball go left, and the right side goes to the right. And when you hit a brick, it explodes with a crisp, smoothly animated pop. It has to be the most satisfying pop in any Breakout clone I’ve played. It’s the glue that holds this game together.

Un-Breakout

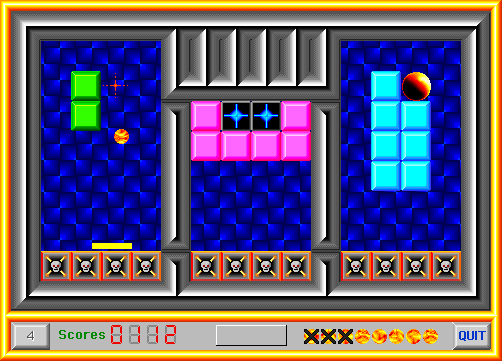

What would happen if you literally flipped the board on Breakout? That’s what happens in M. C. Sumner’s Un-Breakout, and it holds a mirror up to the original Breakout concept, what works well with it, and what doesn’t.

In Un-Breakout, you need to defend the bricks with your paddle. Even though that completely inverts the game, it still has the same rhythm. The easiest part is hitting the balls back, because that’s something you have control over. After that, it’s all luck. Once the balls hit the bricks – in this case, because you missed the balls – who knows how many times they’ll bounce around and how many bricks they’ll break.

Normally this is where Breakout gets annoying. If you’ve ever played a ball-and-paddle game, you know that frustrating moment when there’s one brick left and you can’t get the ball to hit it. In Un-Breakout, it’s the opposite. As the density of bricks decreases, they actually get easier to protect! The same randomness that slows down the game actually works in your favor when you’re playing from the other side.

Over the long run, Un-Breakout nullifies any advantage you get from playing on the other side of the field by adding more balls each time you clear a stage. But it’s interesting how even with the game turned upside down, it still speeds up and slows down in the same places.

Spore

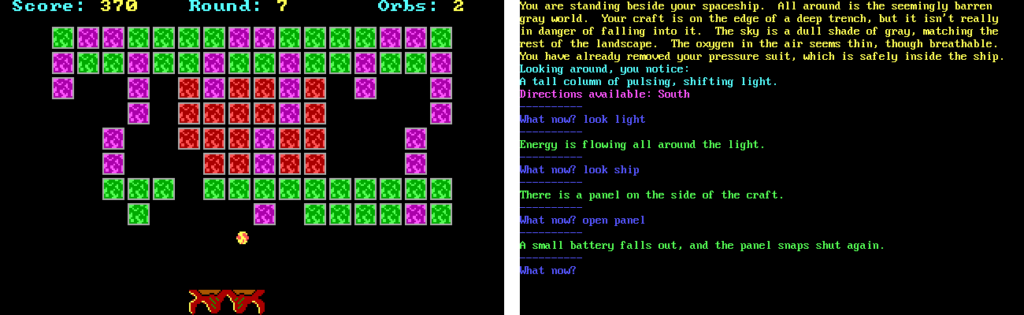

Finally, two genres destined to be together: Breakout and text adventures!

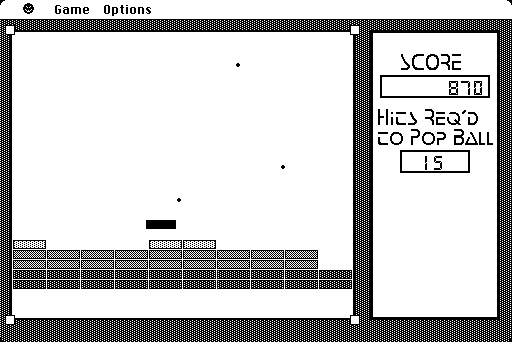

Spore by Mike Snyder sounds ridiculous on the surface – an interactive fiction story that turns into a ball-and-paddle minigame. Neither one is an especially good representation of their genre, though as a concept, they mix better than expected.

As you explore the alien planet Spore, abandoned after the few humans who lived there vanished, you’ll find mysterious pillars of light. Stepping into the light sends you into a brick-breaking game, and if you win, a new passage or item may appear in the world. There’s sixteen Breakout minigames to play, presumably one for each room in the game. These are the main encounters in Spore; they fill the role that a puzzle or a character interaction might serve in another interactive fiction game, bridging one scene to the next.

Neither the interactive fiction nor the minigames are too compelling. There’s not much of a story to tell about Spore and not much to the world itself besides a few clever environmental details, such as the six-toed footprints walking up the face of a cliff. The paddle games, arguably the meat of Spore, are a particularly bad version of Breakout marred by unpredictable ball movement. The game rips off the musical theme from Arkanoid, another frequently copied brick-breaking game, but it doesn’t copy the features that give Arkanoid variety, like power-ups or enemies. It’s just bricks, a paddle, a ball, and your patience. I grit my teeth through a few uninspired brick formations that took far too long and needed too much luck to complete, and I wouldn’t recommend doing the same.

Remarkably, fusing these two halves together is the most successful and effortless part of the game, despite how incompatible the two genres sound. The minigames could have been anything, not just Breakout. They fit in seamlessly because they’re treated as a totally separate side of the game. The text adventure story is just a means to an end, like a level select menu.

One point of comparison might be Puzzle Quest, a role-playing game that’s not-so-secretly a delivery vehicle for a match-3 puzzle game. Puzzle Quest is much more involved (and has competitive play, more connections between the two sides of the game, etc.), but Spore belongs to a tradition of smuggling games into other games.

Takeaways

I didn’t expect there to be many commonalities between this somewhat random selection of games. But the theme that emerges is that no matter how hard you try to change Breakout – turning it upside down, turning it into a text adventure – it is still fundamentally Breakout.

Out of these four games, the one that feels the most radical is Beebop, a game that embraces its Breakout-ness. Instead of trying to subvert the ball-and-paddle genre, it broadens the canvas that the genre can be played on. It reminds me of a similar approach taken by Pac-Man Championship Edition DX, a spinoff game from 2010 that turned Pac-Man (30 years old at the time) into a rapid-fire volley of pattern memorization. Previous spinoffs had tried to reinvent Pac-Man by putting him on a pirate ship or whatever, but Championship Edition DX – the game that feels like it irreversibly changed Pac-Man – is much less dramatic, just tweaking what already existed and ratcheting up the pace.

There could be a lesson in here about the importance of changing something from the inside. Or maybe Breakout is such a simple concept that there’s no way to escape it!

Thank you, sir. I have been trying to find/remember Dragons! for over 20 years. All my phones and pcs have been named in successive social ranks because of this game.

Might be a bit too new for this site but reading this post brought back a ton of warm memories of playing DX-Ball 2 as a kid, which has ever since been THE Breakout game to me. I was wondering if you had any thoughts on it, relative to other breakout games you’ve played?