Flash games and the importance of disposable media

When Adobe announced plans to discontinue Flash earlier this year, people rightly mourned that we’d soon lose the ability to easily play over two decades of amateur games and animation. Gigantic collections, like nearly the entire library of the game platform Kongregate, will rapidly become obsolete. The mission to preserve Flash content is enormous – not only creating a free, open way for modern browsers to understand Flash (like Mozilla’s abandoned Shumway project) but also finding websites with Flash content that will probably disappear soon. Thousands and thousands of Flash games exist, and like any creative works, keeping them accessible is a worthwhile endeavor.

We have to remember why we’re trying to save all that. The importance isn’t specific developers or publishers or games. It’s about recognizing the value of disposable culture and embracing more perspectives on what history should be told. Or, really, whose history should be told.

On last week’s episode of the podcast Reply All, 20-year-old Serbian listener Kris shared how she found the lost Flash game Bunni: How We First Met. Bunni disappeared from the web in 2014, and the saga of how the game was made, lost, and recovered is terrific. The game’s two developers Dan and Andre never saw eye-to-eye: Dan wanted to do a satire of materialistic love, while Andre made something way more flippant and then disappeared into the Outback. (Seriously.) But the core of the story is Kris and her childhood friend who bonded over this strange, cobbled-together game. Bunni reached someone, and however accidentally, it made a difference in the lives of two girls on the other side of the globe. Their experiences – and the experiences of Dan and Andre, working on a game with clashing artistic visions – are as valid as those of the myriad people affected by Star Wars or Final Fantasy.

The podcast had good timing. Days later, it was September 25th, the ten-year anniversary of the massive global release of Halo 3, one of the most commercially successful games ever. September 25th was also the ten-year anniversary of Hot Wheels: Beat That, a game so totally engulfed by the enormous black hole of Halo that it basically didn’t exist. (My friends and I thought this was hilarious. Anyone going to the Hot Wheels: Beat That launch party?) And yet a decade later, you can find corners of the internet that enjoyed the Hot Wheels game. Certainly not a community, but enough people that it undeniably made a dent in the universe.

The world is made up of so many little moments like that, connections formed with ephemeral pieces of media.

As a whole, the things we consider disposable are as much part of our cultural heritage as the most popular, influential titles. Flash games had a huge audience. Regardless of their individual merit, they mattered to people. Most people didn’t play Bunni, but they might know a Flash game made by one or two people that was significant to them. More of my friends relate to gaming through Bubble Spinner than Halo. Just like homemade zines and small press give us a window into the time and communities they came from, Flash works are interesting both as fun things to play and as pieces of the stories of users in the formative years of the web.

This is a discussion bigger than Flash. It encompasses shareware collections, throwaway mobile games, fangames, personal tabletop role-playing game experiences, and Hot Wheels: Beat That.

When we talk about the history of games, it tends to be in terms of major consoles and notable commercial titles. We’re telling a very limited perspective about who games are made by and who played them. Gaming is richer than that. Kris, Dan, Andre, and the Bubble Spinner fans belong in there too, and they deserve an understanding of the history of games that includes their experiences.

Something that always surprises me about Flash games is their reach. Our conservative estimate of how many people played Bunni was in the multiple millions, or about half of the 5 million copies the first Halo sold. Another Flash game we worked on was played by tens of millions.

The key difference of course is that Halo had a lot more economic, press and community systems behind it. Being the tentpole title for a billion dollar console launch does that. Still it was amazing what a Flash game could accomplish all on its lonesome.

Danc (one of those Bunni guys!)

If I started a let’s play of every flash game I liked I might be able to cover every single game I played before they shut it down. One good thing that we have on our hands is the fact that old versions of browsers exist, however scary they may be.

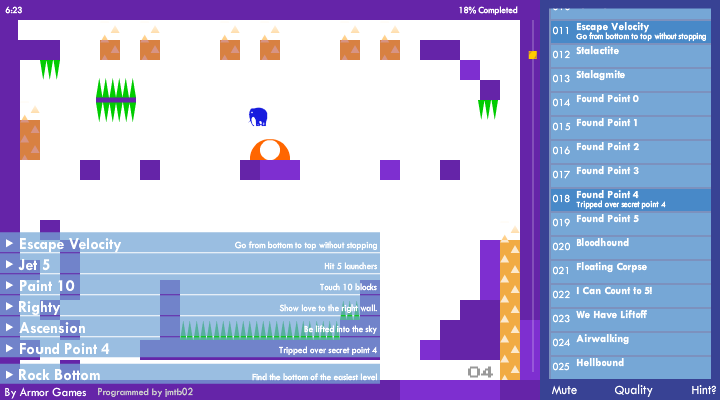

Hedgehog Launch developer jmtb02, who ended up working at Kongregate, gave a “postmortem” of Flash that should be just as interesting to anyone who is concerned about what will happen to Flash. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65crLKNQR0E