Muriel Tramis speaks about her career and the memory of Martinique

Muriel Tramis has a quiet but powerful legacy in gaming. As a designer and producer at French studio Coktel Vision starting in the late 80s, Tramis worked on about a dozen titles, like the puzzle series Gobliiins. But she may be known best for her socially charged games inspired by her family’s history on the Caribbean island Martinique, such as the colonial mystery game Méwilo and the incendiary slave rebellion game Freedom: Rebels in the Darkness.

Tramis left Coktel Vision in 2003 after the company merged with Vivendi Universal Games, and she’s kept a low profile since then. Now, Tramis is stepping back into games with a remake of Méwilo, her first game, for its 30th anniversary. Tramis launched a crowdfunding campaign for the game last week.

To promote her return to gaming, Tramis unexpectedly contacted me a few weeks ago and, in one of her first interviews in English, shared more about her time with Coktel Vision, the importance of historical memory to her work, and what she’s been up to for the last 15 years.

Tramis’s interest in games came from a lifelong love for technology and science. She grew up in Martinique but left for France at age 16 to study engineering at Institut supérieur d’électronique de Paris. Surprisingly, before joining Coktel, she worked in the weapons industry, spending a five-year stint with French manufacturer Aérospatiale programming military drones for missile testing.

“This was not an unexpected field,” Tramis said. “It was rather normal when leaving an engineering school. By contrast, it was my new orientation to video games that was rather strange.” Around this time, some of the earliest graphical adventure games were being released – Tramis calls Lucasfilm Games’s Maniac Mansion one of her favorites – and she became interested in the computer as a storytelling tool. “I felt it was an innovation in digital technology. […] I wanted to create games with the same ingredients as cinema, a universe, characters, dialogue, intrigue.”

“I wanted to create games with the same ingredients as cinema, a universe, characters, dialogue, intrigue.”

So in 1986, Tramis went to Coktel Vision. She started at the small company as part of a marketing study on palettes in advertising but quickly became a game designer.

Tramis describes the company as having a “start-up atmosphere” that encouraged experimentation, autonomy, and risk. She attributes it in part to Coktel’s co-founder Roland Oskian. “Roland Oskian, director at the time, was convinced that to leave the freedom to the authors was a guarantee of quality,” she said. “The counterpart was that I had to give the best of myself. The path was not marked, it was necessary to invent everything.” In that spirit, Tramis “proposed to program a game that I thought totally original. It was Méwilo.”

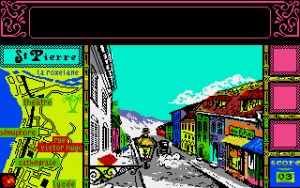

The game takes place in Saint-Pierre, Martinique on May 7, 1902, the day before the town was destroyed by the catastrophic eruption of Mount Pelée. You play as a paranormal psychologist summoned to Saint-Pierre to investigate a zombie – the spirit of slavemaster who haunts his plantation. To solve the mystery, you explore the history of Martinique and confront the legacy of French colonialism, how slavery and rebellion shaped the island.

Méwilo draws from a plethora of Martinican influences. The game came with a recipe for callalou, a Creole leaf stew, and a cassette tape featuring a song by the Martinican band Malavoi. “Malavoi is and will remain my favorite band,” Tramis said. “I like their original use of the violin, a European instrument, in the Caribbean rhythms (biguine, salsa, mazurka Creole…). It is mixed music par excellence. I found it well adapted to the atmosphere of Méwilo, symbolic of Creole society.” Tramis drew the plot of Méwilo from the Saint-Pierre legend of gold jars, a horror story about plantation owners burying their riches and murdering a faithful slave so their spirit would protect their fortune. And she was also inspired by Martinican literature. “As a teenager,” she said, “I discovered the very special writing of West Indian writers (Joseph Zobel, René Maran, Roland Brival, Simone Schwartz-Bart, Edouard Glissant, etc.) and I saw the birth of the literary movement of Créolité.”

“Any novelist or filmmaker connects with the desire to speak about oneself, one’s own history, one’s place in the great history.”

One of those foundational Créolité authors was Patrick Chamoiseau, who Tramis had admired since she was 14 years old. She brought him in to write both Méwilo and Freedom: Rebels in the Darkness. (Despite the unfamiliarity of the medium, she didn’t consider it that different than working with a writer on any other creative project. “It’s like when you call on a scriptwriter or a dialogist in the cinema,” Tramis said. “It’s not him who plays the camera or who directs the actors, everything rests on the director.”)

“Almost all my titles were inspired by the tropical zone,” she said. “Caribbean, Brazil, Florida… only Geisha went elsewhere.” Freedom would later depict a slave rebellion in the same plantation as Méwilo, and Makandal, a slave from Freedom, appears in her game Lost in Time. Tramis previously declared she had a responsibility to tell the stories of her ancestors, and she echoed those comments. “Any novelist or filmmaker connects with the desire to speak about oneself, one’s own history, one’s place in the great history. It’s the same for video games, which is a medium of expression like any other,” she said.

Tramis had the agency to develop personal, historically provocative games like these, and the diverse staff at Coktel Vision supported her. “Employees came from everywhere and were all colors, as is often the case in Paris,” she said. Her work encountered “no resistance, neither inside nor outside.” She considered her use of social, racial, and political themes an innovation for games, saying the “change of scenery” from “the universe, the characters and the intrigues […] caused curiosity.”

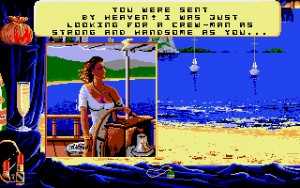

“I knew my audience was mostly male, my team were male, so it was only natural to talk about male desire.”

Though it should be noted that Tramis was working within the expectations of the “geek masculin” culture of game development. Emmanuelle: A Game of Eroticism has been criticized for changing the source material, a 1974 film about a woman on a sexual walkabout, to the perspective of a man on a sexual conquest; Tramis responded that “I knew my audience was mostly male, my team were male, so it was only natural to talk about male desire. However, my heroes were female and free, which was not usual at the time. We did all this with humor. Nobody was upset in the team.”

Some of Tramis’s other games focused on social topics as well, like the cartoony adventure game Woodruff and Schnibble of Azimuth‘s focus on class, labor, and capitalism. In these cases too, she talked about those themes as useful innovations. “It’s just an interesting dramatic spring. Having to free yourself from oppression or escape from a machination works well in an interactive scenario,” she said.

While all this was happening, Tramis also pursued a lesser-known career developing educational games. Coktel Vision began as an educational game company, which was one of her reasons for joining the studio. (“I always liked teaching. I could have been a teacher!” she said.) Tramis was “convinced of the pedagogical potential of video games” and led the development of La Bosse des maths, a series of math games for an elementary-aged audience; with her own experience loving science and technology at a young age, she specifically wanted to make the Bosse des maths games for young girls because “I wanted them to be less afraid to embrace a technical career.” She also co-created the Adi and Adibou educational franchise, which continued after her at Coktel Vision until the company closed in 2011.

When Sierra purchased Coktel Vision in 1993, Tramis began working with larger teams in more of a production management role. But it didn’t change her approach to development. If anything, it improved their outlook. “With Sierra, the internal mood has not changed much,” she said. “We became aware of having a wider audience outside of Europe and took even more care in our developments. […] [We] remained a human-sized studio.

“When Vivendi Universal occurred and Roland Oskian left, that changed. No more freedom. Profitability first, less risky decisions.” Tramis exited the game industry a few years later.

She instead chose to explore new applications for her interests in computer art and educational tech, and in 2003, she started Avantilles, an enterprise 3D modeling company. “I wanted to apply virtual worlds technology to urban planning, architecture and archeology,” Tramis said. “It was a growing field but certainly less creative.” The same ideas she pursued in games continued in her work here: one of her larger projects was a reconstruction of 1902 Saint-Pierre, the same city from Méwilo.

Tramis drifted away from games and towards innovations in 3D graphics. “At that time I completely stopped playing [games],” she said. “I was rather attracted to animated films. Because 3D has become immersed in cinema too, with amazing special effects, the realism has become incredible.” She did mention an interest in Assassin’s Creed and Final Fantasy, two games franchises with technically accomplished visuals from the last decade. (The Discovery Tour mode in Assassin’s Creed Origins, which uses its detailed, interactive Egyptian setting for history education, seems like it would interest her.)

During this time, Tramis wrote two novels that continued her commitment to cultural history, the semi-autobiographical Au coeur du giraumon and Contes créoles et cruels, a book based on supernatural Martinican folk tales. She also said she’s working on a retrospective of her experience at Coktel Vision.

But Tramis wants to create again. Although she dreams of one day “creating a great animated film,” Tramis decided to revisit Méwilo for a modern audience. Why now? “Sentimentality,” she admitted, “because it is my first. It’s like the first kiss, you do not forget it…”

She’s “a little” surprised that people remember her games. “I thought we had forgotten them… It’s thanks to the current trend of retrogaming that we rediscovered them. And they are not out of date.” She added, “Times have changed. The subjects that Méwilo and Freedom deal with, colonization and slavery, have become more sensitive with better study.” For Tramis, the lasting importance of her games is historical remembrance, and it sounds like she believes that has been lost. “The duty of memory has passed by…”

That can always change. Thirty years later, Tramis still believes that interactive storytelling is always open to change by independent developers. “Everything is still to be reinvented,” she said. “It must give way to the imagination of the authors and financially supporting their creations.”

As far as Malavoi goes? She recommends Le meilleur de Malavoi, their greatest hits album.

This interview was edited for clarity with Tramis’s permission.

(If you’d like to hear more from Muriel Tramis and you speak French, see this interview she gave last this year with game researcher Sébastien Genvo. And please translate it!)

Pingback: Muriel Tramis – French Touch — Games criticism

Pingback: A First Lady of Gaming | The First Black Female Game Designer – The Icon

What a wonderful profile of the author. This are stories that need to be told, thank you for sharing it.