Crystal Pixels

The void is quiet. Silent, in fact. A giant star nicknamed Sunny rests in the center of the void, orbited by hundreds of tiny, glistening planets. Within the empty, lonely world of Crystal Pixels, those distant points of light – the crystal pixels of the title – are like little beacons. They lure you out to the deep with the hope that you’ll find somewhere to visit in all the darkness.

The game was the work of a single person, who created it for themselves as a personal retreat. For anyone else, it can be maddening to play. It demands your willingness to go far, far out into nothing, struggle to reach a destination, and decide your own reason to head there.

Crystal Pixels was one of the first games by Alessandro Ghignola, an independent Italian developer best known for the cult hit game Noctis IV. Like Crystal Pixels, Noctis IV asks players to explore an open-ended universe and visit foreign planets. That game has drawn comparisons to the big-name planetary exploration game No Man’s Sky, and Crystal Pixels is on a similar wavelength.

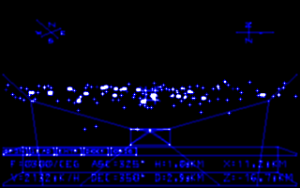

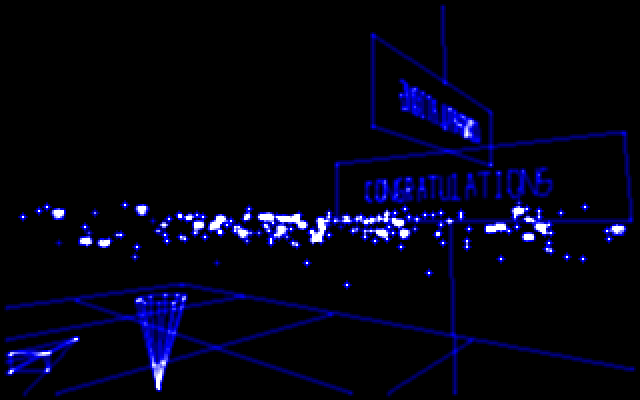

You pilot a spaceship, affectionately called The Fly, through the empty void towards one of the pixels dozens of kilometers away. Everything in this universe is made out of blue light, glowing white at its most intense. When you’re close enough to a pixel, you can land the ship in its atmosphere and investigate it. The surface of each pixel is constructed from boxy, wireframe shapes and spires. They’re almost like rectangular mountains. Are they artificial or natural? They’re yours to discover, decipher, and play around on.

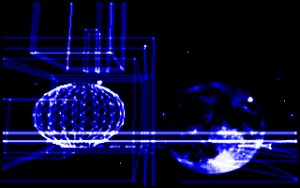

The pixels have little decorations you can move around, like small geometric models or a lamp. If you want to add more, you can create new objects by flying through the heart of Sunny. (Luckily, it doesn’t hurt.) When you fly through the star’s corona, you’ll come out the other side holding something random, or, if you get closer to the center, even a whole new pixel to plant somewhere out in space. You can grow your own universe, but it’s optional, and you can simply explore what’s already out there. You make your own meaning here. It’s only you and these strange, monolithic satellites. They just… are.

If you stand on a pixel and look out into space, you can see all the other pixels orbiting Sunny, framed by the weird structures around you. It’s a beautiful sight. It recalls the view of a city skyline at night. The sky is full of energy, but stranded out on this strange boxy planet, totally silent and so far from anything else, it feels lonesome.

That reflects the mindset of Ghignola, who told me he created both Crystal Pixels and Noctis IV as places for solitude:

Their common trait I put effort in was characterized by a pretty large empty territory and a quest for isolation. They were coded while I was attending school and was forced to confront other people every day. I needed places to escape to where there wouldn’t be anyone but me (or whoever else used the program). Their “calm” atmosphere was driven by a preference for reflection, and because noisy places and wild sensory stimulation are factors that tend to bother me.

Crystal Pixels was a deeply personal game. Ghignola made a place he could visit to get away from the rest of the world. (He assumes he’s neuroatypical.) He fashioned one of the pixels into a home of sorts. It had a sign on it that says “Home Sweet Pixel,” which became the name for his software company. You can still find his home pixel in the original Italian version of the game, available on his website.

And now, you can visit that empty universe and find a place for yourself too. The game’s website has a snippet of lyrics, from Placebo’s song “Every You Every Me,” that sums up the relationship between the player and this “depressive microcosm,” as Ghignola called it: “All alone in space and time / There’s nothing here but what here’s mine.”

This personal void was Ghignola’s long-time pet project. The developer says he was inspired by Damocles, the second game in the Mercenary series, another free-range space exploration game with limited 3D visuals. This was his first time working with 3D graphics, and he was excited to challenge himself by learning how to create a game like that. Development started in 1994, and he continued tinkering with the game through 1997.

Features were frequently added and removed to fit within 64 kilobytes of memory. In one cut feature, you could talk to the cubes living on the pixels, like having a limited conversation with a chatbot. (“Maybe I was just oscillating between wishing to stay alone and getting some company,” he said, “albeit synthetic in nature.”) The game also once had sound effects – eerie and echo-y, of course – but he dropped them since they were dependent on old Sound Blaster hardware that newer devices didn’t support. Crystal Pixels was always a work-in-progress, hence the label on the title screen that calls it a “prototype version.”

Ghignola’s games were never intended for public release. But when he got his first website on GeoCities, he decided to “fill that home page with stuff about myself and see what others would think about it.” The stuff included the earliest version of Noctis, and in 2003, on his own webspace, he released Crystal Pixels too.

Ghignola called Crystal Pixels “one of my programs I love the most.” He also said he “still can’t believe it’s here, because it takes guts to present such a crazy thing.” It is indeed a crazy thing. For all its lonely, contemplative beauty, Crystal Pixels is at times out of control.

Your ship can accelerate quickly, and it has no handle on inertia. You need to go fast to travel within a reasonable time, but once you start moving, you can’t really stop. To slow down, you have to press F2 to face your current heading, then press F1 to reverse the ship’s angle, then accelerate in the opposite direction. It’s exactly as unintuitive as it sounds, and in practice, you keep whipping The Fly back and forth over and over as you repeatedly miss your target. The ship’s display panel contains information about your speed and heading, but it’s illegible. The act of landing on a pixel feels like jumping out of a moving car on the freeway.

Remember that Ghignola created Crystal Pixels for himself. This was his place to visit to be alone. If he was fine with the controls, that was good enough.

If you wanted to, instead, you could take it very slowly, gradually inching your way across space, taking ten minutes to reach your destination. When played like this, Crystal Pixels is something closer to Norwegian “slow TV”, a television genre that consists of long, calm, ordinary scenes, like a train ride or a person knitting. You’ll get wherever you’re going eventually. That could be the game’s secret.

This is indisputably Ghignola’s personal game, and maybe we aren’t meant to play it. To find our own reasons to visit there, we have welcome a calming emptiness of the void.

Trivia!

Based on Ghignola’s old GeoCities page, that shape on the title screen is Fottifoh, his childhood teddy bear. Ghignola also uses the handle Fottifoh online, so in a way, it’s his visual signature.

Downloads

There are two versions of Crystal Pixels available from Ghignola’s website. The English version is at the top of the page. The untranslated Italian release has some additional atmospheric effects within the pixels, as well as the original home pixel and the game’s source code.

Now this is a game I need to play yesterday.

My computer refuses to run this thing, does anyone have any tips?

Hi Zarrg! This game runs in the old operating system DOS, which you can run on modern computers using the program DOSBox.

When you fire up DOSBox, you can enter the command:

Type whatever directory you have the game in, and DOSBox will treat that folder like a virtual drive that it can play from!

Then enter…

Hey everyone! I’d just like to let you know that a fan has made a modern version of Crystal Pixels. For now it’s identical to the old one, except that it runs without DOSbox 🙂

You can download it here: https://github.com/Enet4/cryxtels/releases

The Crystal Pixels fandom is on fire! 😛

I just released an early version of my “Crystal Pixels Playground”, an online tool to view and edit the shapes you can find in the game. All the 3D models from the original game are included (except Fottifoh, for now).

Check it out here: https://github.com/slaimon/cryxtels-editor