Knights of the Crystallion

Bill Williams called Knights of the Crystallion “the game I threw the most of my soul into. […] It was going to be my epic, it was going to be my masterpiece – we called it a cultural simulation – and I thought I could pull it off.” It has a scope so ambitious that it’s absurd for one person to have undertaken: it tries to create an entire society.

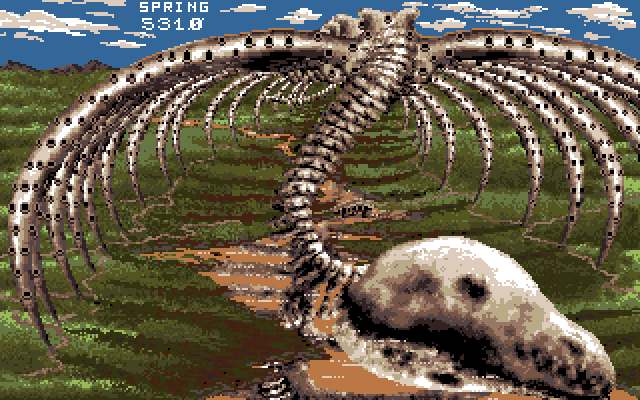

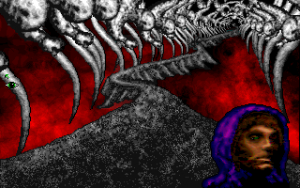

Ages ago, a colossal sea monster called an Orodrid died in a canyon passage. Millions of years later, after the valley was eroded, a nomadic people found its hulking skeleton, “incomprehensible” in size, and declared it their new home. “Orodrid, the city of bone” became more than a shelter. It was the new center of their world, their source of spiritual energy.

In Knights of the Crystallion, you live within this society. That’s the game. It combines a group of confusing, seemingly random activities – like a Nine Men’s Morris-style board game and an action sequence set in twisting cave – to depict the many sides of the communal, religious life of the Orodrim.

Their religion centers on the Crystallions, mythical crystal horses born from the fossilized brain of the Orodrid. To hatch a Crystallion is the city’s greatest, most spiritually righteous honor; they will only appear to those of “great wisdom and leadership” and “purity of soul.” To find your own and earn a place on the Council of Orodrid, you must bond with it over years, seeking its energy as you make expeditions deeper into the Tsimit, the mountain-sized Orodrid skull where the Crystallion eggs rest.

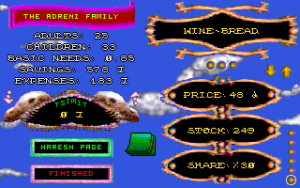

But you aren’t just exploring a giant skull. You belong to the Adreni family, a clan of breadmakers and winemakers who live in one of the hollowed-out ribs of the Orodrid. In-between your expeditions and your spiritual practice, you must help provide for the Adreni by trading with the other clans.

That’s one of the most disarming parts of Knights of the Crystallion. You aren’t a prophesied hero who learns about their people’s beliefs through an exposition dump. You’re just a person. This is your everyday life, a mixture of religious teachings and selling goods. You become part of Orodrid by living in Orodrid… and, honestly, by reading the manual every three minutes to figure out what’s happening on-screen.

The game is an impenetrable work of fiction. It’s broken up into a few disparate activities with little connective tissue, and understanding each one is the key to understanding the others. The best way to explain this world might be how the game does, piecing them together one at a time.

The Tsimit and the Proda

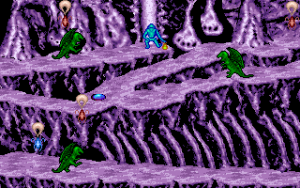

The ultimate aspiration of your life is to reach the Fourth Veil of the Tsimit, the inner sanctum that holds the Crystallion eggs. The city made the Orodrid skull into its civic capital, but underneath that, it resembles a labyrinth of bone. Without guidance, you would get lost quickly in its intersecting pathways that seem to wrap around each other in infinite directions. The Keepers of the Tsimit have given you a suit of armor made from the shells of Crystallion eggs that will light the way, as well as a weapon to fight off the beasts living inside.

Exploring the Tsimit is a scary, unpleasant experience. You have no idea where to go. The screen will sometimes be covered in darkness, which somehow makes the caves a little less intimidating since you can’t see their total sprawl. Through all this, you have a side mission to retrieve crystals before they’re snatched away by these weird flying bug creatures. With the unendingly large maze and the ominous dirge-like music, you wind up feeling marooned in the Tsimit. How long can you throwing fireballs at strange bugs with no relief in sight? The point of all this gets clearer as you discover more about Orodrid culture.

Your Crystallion suit starts with three charges, which prevent you from dying if a creature attacks. In a surprising display of kindness, if you’re nearing death, the game will allow you to back out. A priest will say they are “worried about your ability to continue,” and you can exit right there. This small variation means so much. It frames the option to give up as an act of mercy rather than failure, and it takes the edge off the Tsimit’s hopelessness.

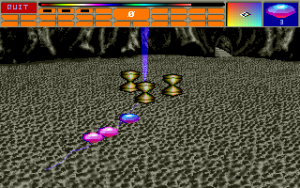

Once you’ve left the Tsimit, you bring the crystals you’ve gathered to the Proda, a ceremony where the Orodrim priests charge the crystals to power up your suit. When placed in the right geometric configuration, the crystals pulsate, shooting electricity at the pylons in the room. It’s difficult to understand, even with instructions. (The best touch may be the Cripids, creatures that live in the Proda room that try to eat your crystals.)

Deketa and Bosu

The Orodrim train their psychic abilities by playing Deketa, a number-matching card game. It plays like concentration; you turn over and match their numbers together to form pairs. However, everything is psychically controlled. You flip the cards with your mind, and as the cards themselves get excited, they shift around on dim candlelit table.

Deketa is meant to enhance your psychic connection to your Crystallion, and it has one of the most effective, creative depictions of psychic powers I can remember in a game. The backs of the cards have convulsive, swirling patterns. As you play more, the patterns faintly start to reveal the card numbers. They flash onscreen for a split second at first, enough to give you a subliminal impression that one card might have a 3 or an 8. As you get better, the numbers stay on-screen for longer. The cards will start shuffling around faster and more unexpectedly to the point where you can’t memorize their positions anymore, so the faint psychic numbers become your only way to match them.

The psychic card game Deketa is also a great example of the game’s technically excellent Hold-And-Modify graphics, remarkable for 1990

The gradual progression from memorization to psychic prediction is exciting as hell for a card game. Once you’ve enhanced your psychic connection enough, the Crystallion will project its image into the Tsimit to guide you on the correct path to the next Veil. (A ghost horse! A ghost horse!) At the height of your power, you can manipulate space, allowing you to leave the Tsimit whenever you want. These connections reveal some of the clearest ways that different parts of the Orodrim culture fit together – a leisure activity bleeding into religion.

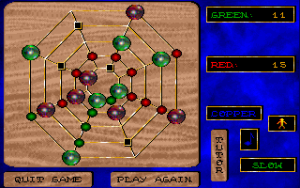

The board game Bosu has less of a clear connection. It acts like the city’s version of Go. Players take turns making paths by placing stones on a spider web-shaped board. The theme ties back to an old Orodrim belief about making more from less, according to the manual, but it’s basically a neat board game plopped into the game. Though not everything in a culture has to be deeply symbolic, the importance of Bosu seems arbitrary. The Keepers of the Tsimit will challenge you to Bosu every time you reach a new Veil, and that’s the extent of its role in the game. Even if the philosophy is clumsily inserted, it resonates: Orodrid values its generations of perseverance.

The Haresh

The Haresh simulates the city’s economy. It’s overwhelming and frankly not interesting to engage with, but its ideas bring the world into focus. They complete the game’s conception of Orodrid as a place inhabited by a real people.

“Haresh” refers to each of the ribs of the Orodrid, where people have lived for generations in self-contained cellular economies. (The manual says this practice started after the Orodrim quarantined themselves following a disease outbreak. This problem has been solved thanks to improved sanitation, but the separate cells stuck around anyway. These details really build out the notion of how very long this culture has been around and how much they bond over their traditions.) The families in the Hareshes specialize in different trades, like pottery and literature, and to subsist, they sell their goods to each other.

The complex economic simulation has so many factors to consider. You set your prices based on an analysis of their quality and market share compared the other clans. Your family has a base level of needs, represented unintuitively as a decimal value; you need to buy quality products to keep them well, but you also want to keep enough money saved up in case you weather a difficult season. Periodically, you’ll also want to offer a tithing from your profits to the Tsimit to help run the school, the hospital, and the government (and to keep yourself in their good graces). The game presents all this information as a dry set of numbers. I had no desire to play around with this portion of the game more than necessary.

Yet the Haresh shows Orodrid’s humanity. There’s a communal spirit to the Haresh market rooted in a proud sense of rugged interdependence. When tragedy strikes a family (an illness spreads, outsider bandits attack, whatever), the rest of the Haresh will chip in to cover their loss. But if a family isn’t pulling their weight, including yours, the Haresh will eject them. Tough love.

The Haresh is not enjoyable, and the need to participate in the economy disrupts a game that’s otherwise about mysticism and culture. It is, however, a reality for these people. Although the Haresh could’ve been executed without so much bookkeeping, the game deserves at least begrudging admiration for putting the laborious internal consistency of its world above all else.

The Orodrim honor their traditions for a reason. This big bony city offered their ancestors an opportunity to build themselves up, and now it offers the same to them.

Putting Orodrid together

Bill Williams told Amazing Computer Magazine that Orodrid was inspired by a Yes album cover by Roger Dean depicting people living in a gigantic bone valley. Orodrid does have a Roger Dean quality to it, with its vast, weird, curling stretch of landscape. It looks beautiful as the seasons cycle and the valley fills with leaves or snow. But the setting has more dimension besides awe.

Seeing the full picture of Orodrid requires that you circle the game for a while, dabbling in each of its subsections multiple times. It asks for more patience than you may have for this strange, inaccessible game. Exploring the Tsimit will seem pointless at first, no matter if you read the manual. Bosu has a weak connection back to anything else. The Haresh is a chore. Decades of in-game time pass by. But if you persist, you begin to see the personality and contradictions of this unusual city.

Orodrim society has an odd division. On the one hand, its people live in self-reliant clusters, leaning on each other for support. But it also has a ruling class, the elite in the Tsimit who ask for donations and command the spiritual might of the city. These aren’t incompatible. At its bedrock, this society worships the Orodrid. It provides the foundation for their families and their communities. They defer to the spiritual wisdom of those who have communed with the Orodrid through the Crystallions, and for the most part, the rulers seem content to let the communities live on their own.

Knights of the Crystallion roots everything in this worldview. The soundtrack is horrifying, thudding, slightly off-pitch. It has tribal sound that alternates between ancient secrecy and violence – not just ominous, but suggesting that your actual death is imminent. It’s not meant as a threat. Orodrid is spartan, and its music reflects that.

The game even incorporates its technical constraints into the fiction. Because of how the game handles numbers, there’s an upper limit to the amount of currency you can have, so the manual explains it by saying that any excess money is distributed to the other families to help Orodrid’s prosperity. (Brilliant!) Or the game’s copy protection – its way to check that you purchased a full copy. As part of your initiation into the next Veil of the Tsimit, the Keepers will quiz you on your knowledge of a book of Orodrim poetry that came with the game. Nothing is allowed to exist outside the game’s mythos.

Experiencing this for the first time left me in shattered confusion. It’s like going to a religious service you know nothing about and trying to follow along respectfully as best you can with the person next to you. You are not in control of this. Your own goals happen within the context of a layered society of craftworkers, steeped in ancient tradition and values based in their home. The culture isn’t spelled out to you. It has to make sense from what you do, and for a while, it probably won’t.

Knights of the Crystallion is almost like a thought experiment. What does an anthropology game look like? It may not be pleasant or approachable. If Williams had more time and resources, as he lamented, maybe it could have been. But it needs to be experienced just for the audacity of what it attempted.

This was a fascinating read. Thanks for writing it!

This is wild, I love it! Great piece!

Absolutely enamored by this. If I were little and I’d had this weird, impenetrable game, I would have been WAY into it. Absolutely fascinating. I found someone who had uploaded the soundtrack cassette to Youtube. Haunting and moody! Any idea if there’s a tracklist somewhere on the internet?

Great read. The game made a lasting impression on me. I still have the disks (and officially bought to!). I was cleaning my storage space a few days back and found the disks. The phrase “Orodrid, city of bone!” immediately entered my mind. I can’t remember playing the game a lot but some of the ideas in it stuck. I did some googling to relive the game and then I found this article.

I was also amazed at the reviews the game got at the time. Very considerate of the game and generally high marks. Nowadays a game that tries something different usually gets slaughtered in the reviews. It made me long back to a time where there was lots of experimentation before a lot of the genres where set in stone.

I’m saddened by the fact that Bill died at such a young age. But seeing those disks made me smile and I’m considering to use some of the lore and concepts of his game with my Pen & Paper RPGing. I guess you are never really gone if people still remember you.

Nice to know I’m not the only one who can’t get this game out of my head. Even if the maze game at its heart was always rather underwhelming, the wonderfully disconcerting music and sound effects, and essential otherness of it all, made it special. It’s stuck with me more than any other game of its era, even though many of them worked far better as games.

Thanks, was a great read about a fascinating game! I really have to recommend Jimmy Maher’s article about Bill Williams on this occasion: https://www.filfre.net/2016/01/bill-williams-the-story-of-a-life/