Alien Logic: A SkyRealms of Jorune Adventure

When you wake up on the planet Jorune at the beginning of Alien Logic, the first creature you meet is a Thriddle. They’re a species of alien scholars who live in the Mountain Crown, and it’s a good thing they found you, because there’s a lot to catch up on. Before you even have a chance to get your bearings, the game launches into a wall of exposition that covers the last 3500 years of history on this planet, including a sequence narrated by someone who sounds almost but not quite like Leonard Nimoy.

It’s pretty excessive, but the game certainly has a lot of material to cover. Alien Logic was based on an obscure tabletop role-playing game from the 1980s called SkyRealms of Jorune. It’s a deep, weird, and politically complicated setting, and not one that’s easy to step into.

Jorune is the star of Alien Logic, with a beguilingly weird cast of characters and stories, so it’s surprising how little time on the whole we spend with them. Alien Logic is not by an stretch a traditional role-playing game. How does a world like Jorune fit into a game like that?

The reason Alien Logic might be so indulgent about its backstory is that it was actually designed by the team that wrote the original SkyRealms of Jorune gamebook. The game’s publisher, Strategic Simulations Inc., was most well-known for their computer game adaptations of Dungeons & Dragons scenarios through the 80s and 90s called the Gold Box games, but when their license for D&D expired, they wanted to work on new ideas. Partly that was out of necessity, but as SSI producer Bill Dunn also said, the company wanted to start taking more liberties with game design than they were previous allowed to under the D&D license.1

That’s when they were approached by Andrew Leker, one of the co-designers of SkyRealms. Leker had learned programming at the Naval Postgraduate Institute, and despite his inexperience leading a digital project at this scale, he pitched SSI on developing a new game inspired by the SkyRealms rulebook.1,2 It seems like it fit everything SSI was looking for – a new intellectual property that they had permission from the original creators to play around with, because they were the ones making it. It was the first video game from Leker and his SkyRealms collaborators Miles Teves and sister Amy Leker Kalish,3 and it was the only video game they worked on together as a team.

The world they created is truly unique. Jorune is home to a menagerie of strange alien creatures, who live side-by-side with humans in an uneasy peace. Thousands of years ago, it was a quiet planet, teeming with magical energy. Then the humans arrived. Wielding a fleet of advanced technology, they attempted to colonize Jorune, and the resulting war between science and magic left both sides in ruins. In the wreckage of the conflict, a bizarre and diverse society has flourished, combining the old ways and the new.

Most of the inhabitants of Jorune are trying to carry out normal lives in this fractured society as merchants, farmers, or scavengers, like the Bronth, the bear-men from the Dobre continent, descendants of the original bears brought over from Earth, who are much more soft-spoken than their fearsome appearance would suggest. But over the years, each species has built up their own set of alliances and grudges. In the de facto capital city of Ardoth, where nearly a dozen types of aliens live together, you can tell that everyone is waiting for something that will shift the balance of power.

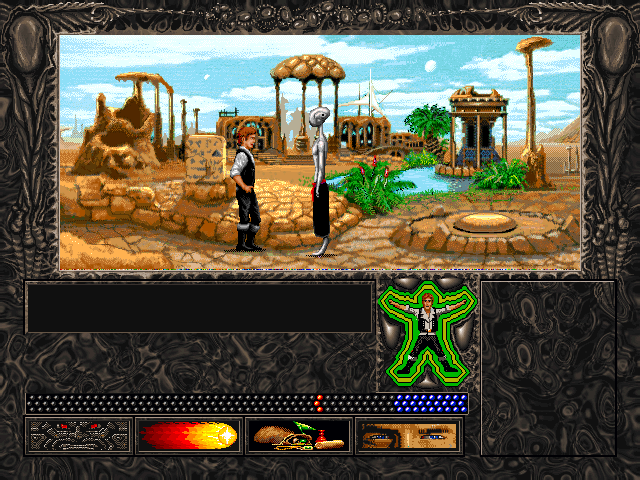

Jorune feels ancient and improvised, like it was cobbled together from old bygone cultures and rituals, which have lost their original meaning and have mutated into something new over hundreds of generations. It reminded me of the worn-out settings and strange creatures from the dustier corners of the original Star Wars – a comparison made easier because the main character in Alien Logic looks exactly like Han Solo – or more specifically, it reminded me of the movies produced in the wake of Star Wars that tried to imitate it on a lower budget. There’s a strong similarity to David Lynch’s 1984 adaptation of Dune, how the collage of sacred, primitive, and militarized design just amplifies the extravagant weirdness of what’s happening there.

Leker and company clearly put a lot of care in translating the world that his team designed into a computer game. There are times when Alien Logic feels like it’s an excuse to explore more about the lore of Jorune than the writers could’ve gotten away with in a tabletop campaign, and they’ve earned it. A disproportionate number of the characters you meet are scholars or historians who want to share their research about extremely niche topics, like the Lelligirian Limilate Scare, and Jorune is so unusual and captivating that you’ll want to stick around to listen. That’s why it’s so surprising that, despite the attention that Alien Logic lavishes on its world, the game doesn’t actually have much of a narrative.

Alien Logic is an incredibly open-ended game, so much that it often lacks direction or purpose. Early on, it’s established that your mission is to track down an indigenous terrorist known as the Red Shantha, who has begun attacking human cities in an attempt to reclaim the planet back from its colonizers. (It’s understandable – and probably justified! – but it’s much less of a sympathetic cause for your character, who is the sole human survivor of one of the attacks.) The only way to find the Red Shantha is to go out and explore the planet. You’re going on this mission alone, and after some initial guidance from your friends the Thriddle, the game leaves you by yourself to look for clues, fight wild monsters, and forage for resources. Hours can pass by without visiting a town or speaking to another character. A substantial amount of the game is spent digging for crystals out in the wilderness in complete silence.

This was quite a shock! After spending so much energy building up the complicated political dynamics of Jorune, the game quickly puts that in the background and gets you started on the tedious work of gathering resources. Despite coming from a publisher that specialized in Dungeons & Dragons games, most of Alien Logic actually has more in common with a modern survival game like Minecraft.

It’s true that role-playing games can have long periods of grinding and wandering built into them, and Alien Logic is no different, especially for its time, but for a game that invests so much in its world-building, it’s unusual how far it drifts away from that once you’ve made it through the introduction. It’s like switching to a completely different game with the same characters and setting – or it’s simply a very awkward adaptation of the ideas in the original SkyRealms. It’s worth keeping in mind that based on the credits, this was the first computer game that any of the designers of Alien Logic had ever worked on; it would have been quite an undertaking for them, and this might not be how they meant it to turn out. Andrew Leker would express mixed feelings about his work on the game a few years later.2

With that said, Alien Logic is still a role-playing game, and role-playing is about more than advancing a story. It’s also about inhabiting a world and a character through your actions, and in that respect, it’s impossible not to get wrapped up in a setting as distinctive and all-encompassing as this one. Every RPG convention in Alien Logic has been twisted into the unfamiliar language of Jorune, and you’re constantly reminded about the innate alienness of this world’s culture – its alien logic, if you will – simply by having to play inside it.

Unlike most RPGs, for instance, there are no experience points, stats, or leveling up. Your character is one of the few humans who practices the magical art of Isho, and it’s not something you can become instinctively better at. Instead, to gain new powers, you have to travel to a surreal dimension of energy known as Weaving World, a name sounds just enough like the Weirding Way combat art from Dune that I feel justified making another comparison to that franchise’s brand of mystical space weirdness.

Isho powers can be used to attack, defend, or just delay. Trapping enemies in a suspension orb is a great way to hold them off

Even the monotonous digging sections have an alien twist. The tools you use to dig up crystals are actually organic robots, designed thousands of years ago with old technology from the human colonists. These “recos,” as they’re called, are a prized commodity that are bought and sold in the marketplace, or you can hatch them yourself by finding their eggs out in the wild, which opens up the door to a whole economy of genetic manipulation gadgets and creature shops. As you discover, genetic engineering plays a major role in the history of Jorune, but your first exposure to it will probably be when you botch a reco egg and it blows up into a mess of genetic goop.

During the sparser sections of the game, these are the sort of things that make Jorune come to life. But still, there’s only so long you can go around looking for herbs before it starts to feel a bit meaningless. The game struggles when it goes too long without some semblance of stakes or direction to anchor it down, which it does frequently, particularly the first half.

When Alien Logic manages to get both parts of the game going at once – bringing the narrative elements back into focus while you’re out exploring temples and hunting monsters – it starts to make sense as a whole world as the creators of SkyRealms intended it. It’s a place of ancient wonder, but it’s also home to societies with their own practical concerns, where sacred artifacts are just as likely to be studied by historians as they are scavenged and traded around by art collectors. Every encounter in Alien Logic, even just bumping into somebody on the street, gives you a better sense of how you fit in the middle of this bigger picture. The character writing is so consistently strong that it makes every part of the role-playing experience more meaningful.

I loved meeting all the different factions of Jorune, like my problematic faves, the Trarch, a tribe of dim-witted ogres on the southern island of Drail, who threaten to eat everyone they come across but are also exceedingly polite about it. On your way to purchase some more recos from the market in Ardoth, you might see a group of Woffen, the wolf-men of Jorune, protesting outside the marketplace for equal labor rights. In the back corner of the Shambo Shenter tavern, you could cross paths with a Ramian, a species whose violent crusade to find a healing drug called shirm-eh has turned them into international pariahs and jumpstarted the black market. You can already imagine what he wants to propose to you.

Not all of those encounters add up to something bigger in the story of Alien Logic, but they do help bring this baffling alien world a little closer to reality. Sometimes, there’s a bear in the tavern who offers you a drink and a conversation, and it is what it is.

References

1. Bielby, Matt. (1994, August). Skyrealms of Jorune: Look, Ma — No Elves! PC Gamer, 1(3), p. 12-14.

2. Blevins, Tal. (1999, June 28). Resurrection Interview. IGN. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20001021223855/http://pc.ign.com/news/8615.html

3. Pook, Matthew W. J. (1995, Summer). SkyRealms of Jorune: An introduction. Borkelby’s Folly, 1, p.3. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/nothotai_gmail_S3/BF1/

Man, I loved this game. Nice article.

This was such a fun game, very different and refreshing. To this day one of my all time favorite games and one I still reminisce about now and then. Don’t think I still have the game but I still have the book. The disappointment is I never finished the game, there was a bug in the code that crashed the game every time I got close to finishing. I tried different things, came at the end in different ways but it always crashed