The Madness of Roland

One of the strengths of multimedia was how it can tell a story, or share information, in a way that’s non-linear, even collaborative. It can link ideas together in different orders, enhancing them with sounds, images, and video. Bob Stein, the founder of The Voyager Company, one of the pioneers of multimedia, described it as the future of the book – the next step beyond publishing in print.

In terms of fiction, many existing books were adapted with illustrations, annotations, and commentary. Greg Roach’s The Madness of Roland imagines what a multimedia novel might look like from scratch. It doesn’t just enhance the text with visuals and commentary but uses those as important parts of telling the story and its meaning.

In chapter three, we get to the madness of the title, where the seductive magic of enchantress Angelica backfires and turns the legendary paladin Roland into a rabid, violent maniac. While the rest of The Madness of Roland has been text, the transformation scene is a surreal video sequence, a shifting collage of suggestive religious art, nudity, and horror imagery, creating the impression of Roland’s descent into feral anger. The other part of the chapter is text again, written about the other characters as they grapple with what they presume was Roland’s death. That all wouldn’t be possible in a print book.

Released early in the life of the CD-ROM format, The Madness of Roland crosses the lines between a novel, a play, a radio drama, and video art. Split across multiple perspectives and media, it unfurls a Medieval tale of magic, lust, and legacy, though the way it tells that story is more interesting than the story itself.

The novel is loosely based on two epic poems, The Song of Roland and Orlando Furioso, both about the exploits of the knight Roland. In this version, he is the nephew of Charlemagne, leading the charge in a siege against Paris in the year 778 as he wields the mythical sword Durendal. His foes speak of him as if he has supernatural strength, like a soldier from an ancient Greek legend, and Angelica, enamored with this man, tries to defeat him through seductive magic. Instead, the magic corrupts him, turning him into a force of chaos who goes on a rampage totally fucking shit up. Although everyone at first believes he’s a demon, he retains his consciousness, terrified of what he has become. They discover how to return Roland’s “reason,” yet even while he was an unworldly monster, Angelica still found herself in love with him. Love, of course, may be the real madness.

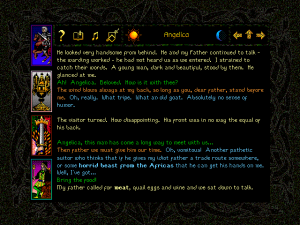

This isn’t told in such a conventional way. Each chapter of The Madness of Roland contains a few “leafs,” short passages about the same period of events written from the point of view of another character. No character has the whole story, and to understand it, you need to read every perspective. They tell their stories in their own voices, and they give you a glimpse into their minds and emotions, like a soliloquy. The text changes colors to indicate their speech, their narration, and their unspoken thoughts.

The voice actors give strong performances, elevating the script with strong personalities. Charlemagne tends to be pompous and ramble about history, while at first, Angelica sounds like a Medieval Daria, rolling her eyes to herself at the over-the-top gestures of her suitors. The voiceovers enhance the text, as do the character themes that play at the start of each leaf, apocalyptic, ominous, droning pieces of music that set the stage for the chaos to come. Put together, it sounds like a radio play more than a book.

The Madness of Roland uses multimedia in other ways, too, to complement the story with external ideas and images. Most every leaf has what The Madness of Roland calls a “sun level” and a “moon level,” supplementary pieces of media that it juxtaposes with the scene. Sun levels have a literary or historical quote; the moon levels are evocative, artistic videos combining live action and animation, and as the game stresses, they “are not necessarily direct illustrations of the story.” At the start of the first chapter, “The Siege of Paris,” the moon level shows a montage of Gulf War footage, including a speech from George H. W. Bush, to draw parallels with then-current events. In one self-aware moment, a sun level brings up a quote from Carl Jung to poke fun at the phallic obsession over Roland’s sword.

At their strongest, the text and videos reflect the mood and direct your thoughts on the story, drawing out themes where they may not be visible. They transform its meaning. That’s the promise of what a multimedia novel like this could accomplish.

At their weakest, they’re just goofs. Within the text itself, bolded words link to references, images, or commentary, but they’re usually just a way to make jokes about the story. They fall short of the quality that the program promises for interconnected ideas that are worthwhile “to explore on your own.”

It has such intriguing ideas for its format, but The Madness of Roland is not an especially strong story. The novel spins its wheels with middling historical fantasy romance that’s both vague and mired in specifics. The characters tend to think in poetic language that’s often beautiful but imprecise, yet the story has so many nobility and chivalry figures that it needs a character index. (Medordo the squire nearly marries Angelica in the middle of the story, and it still has to remind you who he is during the last chapter.) When Roland’s ally Astolpho flies a Hippogryf to the moon to win back Roland’s sanity in a drinking contest in chapter six, it’s told through implication, with a high density of unfamiliar characters and unclear shifts between first- and third-person. That stymies what should be a spectacularly lucid moment, ripe to be explored thematically in words and video.

The story does have compelling points, and they take advantage of the non-linear book format. More than the themes about romance and madness, the main thread through the story is the question of legacy. As the plot progresses, the cast wonders how history will judge them, not whether they’ve done the right thing but how they will be remembered. Charlemagne doubts whether his desperate attempts to save his kingdom will amount to anything; Roland, on the other hand, accepts that he has become a killer and that the only his own judgment can bring him peace. By allowing you to jump into their heads in any order, the story reveals how everyone shares the same worries.

There are a few limited moments of interactivity when the characters directly ask a question to you, the reader

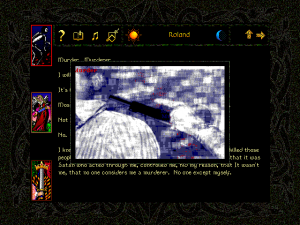

The major characters show an inner life. None are as awesome as Durendal, the sword, who carries her own monologue as the embodiment of carnage. “All of you are meat, sweet meat made for dying. Only steel endures,” she snarls. (Holy shit!) The Madness of Roland seems to condemn her thirst for blood, contrasting her parts with a Lao Tzu quote about the empty pursuit of “delight in killing.” Yet as the story advances, she shows change, first boredom and then remorse, beginning to question her corrupting role in war. She confesses to the reader, in a fragile moment, that she dreams of becoming a human woman and experiencing peace. “Yet,” she continues, “in the shadow time of stillness I yearn for taste and breath I yearn for tears I yearn for other than the thinness of cleaving.”

She’s an incredible, unique character, and she too comes to worry about her legacy. “Will I pay for my sins? The sins of steel. The sins of the cleaver.” I would trade everyone else in this entire novel for more Durendal.

But the multimedia features can enhance the story as much as they can detract from its meaning. In several cases, the choices for supplemental media in The Madness of Roland diminish the characters and their thoughts.

The novel is mostly told from a leering, prurient male perspective, preoccupied with how men look at women, how women are objects of desire, and so on. There’s only really one woman in The Madness of Roland, Angelica, two if you count Durendal, so she gets to be on the receiving end of that (as well as the novel’s confusing treatment of “oriental” characters. She uses magic to make herself look white or something? What?). Hearing the story told from her perspective often provides a chance to learn more about her beyond that framing and to give her a greater depth of personality, like when she finally unleashes her sorceress powers and asserts control. Yet some of the multimedia supplements, especially the sun levels, default back to the same limited viewpoint, about how she’s beautiful and men lust after her. It’s trite, and it clashes with the character development in the main text. It’s wildly inappropriate that, after her growth and vulnerability, Durendal’s final monologue is paired with a creepy text passage from the book How to Make Love to a Woman – like that’s the best way to think about her?

It’s a flawed novel that often struggles to stay true to itself and tell a compelling narrative while grappling with epic themes of love and remembrance. Instead, its strength is the format – the way it expands the story with audio, video, and a deep field of references. Swapping between points of view allows it to explore the emotional and psychological lives of its characters, and that technique finds a perfect home in this versatile, open-ended digital format.

And it doesn’t just matter how but when it told the story that way. The Madness of Roland debuted before the CD-ROM was a widespread piece of technology, when people were still figuring out what to do with videos, full-color images, and large volumes of text on computers. At an early, untested time, it dared try to rework the concept of the novel for the multimedia age.

Trivia!

The Madness of Roland was created using the hypertext development tool SuperCard, similar to the Macintosh program HyperCard. The software was designed by Silicon Beach Software, a company with its hands in a lot of notable development tools: They were also behind the World Builder engine and possibly the first ever game to use a mouse.

This is lowkey one of the most compelling visual novels I’ve read. I can’t say why. It’s short and often amateurish, and makes a lot of choices that I don’t care for. Even then something about it sticks in my head years after I’ve read it. I’m glad it exists.