“The future – we’re there!” Rhizome talks Theresa Duncan and the new age of CD-ROM preservation

(from left to right) Rhizome archivist Dragan Espenchied, Participant Inc. founder Lia Gangitano, game critic Jenn Frank, FEMICOM Museum founder Rachel Simone Weil

Theresa Duncan’s game Zero Zero ends with a fireworks show as the calendar rolls over to the year 1900. “The future,” the protagonist Pinkée cheers, “we’re there!”

FEMICOM Museum founder Rachel Simone Weil mentioned this quote when discussing Zero Zero‘s thematic pining for the future, but it also captures the revelatory feeling of Rhizome’s showcase event for the newly preserved Theresa Duncan CD-ROM games on April 16th in New York City. Their restoration is a watershed moment for gaming – for the revitalization of Duncan’s games, for the importance of diversity in gaming culture, and above all for the relevance and accessibility of the CD-ROM medium. After listening to the discussions and speaking one-on-one with archivist Dragan Espenschied, I left with impossible optimism for the future of these games and other forgotten digital works.

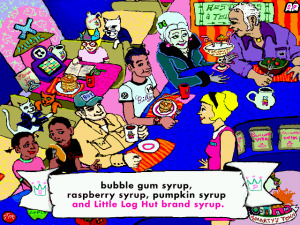

Over her career, Theresa Duncan produced three CD-ROM games for young girls: Midwestern daydream Chop Suey, ride-about-town Smarty, and the wistful Parisian Zero Zero. As Weil and game critic Jenn Frank pointed out, these games contrasted with stereotypical “girl games” in their willingness to play with the growing and slightly naughty sensibilities of children while still celebrating femininity and fashion. (These themes carried throughout Duncan’s art; Participant Inc.’s Lia Gangitano says Duncan had planned to make a violent game based on cosmetics called Apocalipstick.)

Frank referred to that sneaky dimension as the “secret inner life” of girls, and it alludes to a child-like subversiveness that transcends gender. These games speak to kids on their own level, so much so that only adults might notice how effectively they channel those aspirations and modes of thinking. As an example, the presenters focused on Aunt Vera, Chop Suey‘s primary supporting character. The girls playing Chop Suey won’t recognize her as an adult surrogate through which they can imagine their own futures, and it’s important that they don’t. Duncan didn’t condescend. Her games work because of her honesty and irreverence.

Rhizome chose Theresa Duncan’s games not just for their relevance to the emerging (and now necessary) scholarly discussion of gender in gaming but for their synecdochic representation of the CD-ROM medium. The panelists compared Duncan’s works to a series of vignettes or an interactive toy rather than the beginning-middle-end structure typically associated with gaming, and there is no meaningful progress to save. Many CD-ROM games share these qualities; Jenn Frank specifically compared the games to mythology classic Cosmology of Kyoto and Cyan’s Myst predecessor The Manhole. Duncan once mentioned that too much interactive media wanted “more,” and the usual CD-ROM game format often counteracted that.

(For the record, Duncan cited games based on Richard Scarry’s Busytown as an influence.)

Games have only now returned to discovery-driven modes of play in titles like Gone Home. This rhythm applies well to Duncan’s games, as their circuitous and compartmentalized structure appeals to kids. And in general, CD-ROM games have gained relevance as this genre resumes popularity. That’s why digital preservation matters. Maintaining the past is important for its own sake, but these games have purposeful application to the future of the medium as well. As the event participants noted, preservation fills the gaps in our collective digital culture. Designers, critics, and audiences alike can be inspired by older cultural works and bring something new to the discussion, even if it’s just having fun.

To this end, Rhizome assembled one of the most impressive and thorough digital preservation structures I have ever seen. Their work may truly signal a new era for software preservation. I had the pleasure to speak with Espenchied about the technical specifics of this system, and I am effusive about what they might have in store.

Rhizome archivist Dragan Espenchied shows off Macromedia Director 8.5 running on Mac OS Classic – all streamed over the Internet

Espenchied worked with the University of Feiburg’s burgeoning Emulation as a Service program to setup servers that can run up to 750 Mac OS Classic virtual machines at once, each customized to play .ISO disc images of Theresa Duncan’s games. Rather than emulating them on the user’s end, all the work happens overseas and broadcasts back in real-time (similarly to Sony’s PlayStation Now service or the belated OnLive). Archivists have previously used EaaS to access documents and digital works in their native format, but this is perhaps the first application of the service to game emulation. Adventure games and interactive media in the vein of Duncan’s don’t ask for high responsiveness or speed, so the EaaS servers can afford to send high quality audio and video. So you wouldn’t, as Espenchied said, run Quake on the platform. He compares it to Skyping with a computer, and it requires a comparably good Internet connection.

The emulators run in-browser under HTML5, and it could theoretically work on any devise that can view the web depending on browser compatibility. Rhizome’s setup for the Duncan games only uses Mac OS Classic, their system is extensible and could potentially include any number of Windows variants or other systems.

That means that right now, for free, you can run Mac OS Classic on any web-enabled device and play games through it. Think about that. That is huge. This is potentially the biggest breakthrough for game and software preservation in recent history. Espenchied teased that their system might eventually be able to run user-submitted .ISO files, a mind-boggling development that would make emulation and CD-ROM games immediately accessible to anyone, anywhere in the world, regardless of technical expertise. Think about the access barriers that might collapse.

My biggest concern was the system’s long-term maintenance prospect. Web-based services demand upkeep and funding to stay afloat, and something as constantly temperamental as emulation of often-buggy operating systems needs even closer attention (the games crashed at least once during the event’s otherwise seamless demos). Espenchied assured me that overhead was low and that Rhizome had considered future CD-ROM preservation efforts using the same infrastructure. Ongoing projects would provide the necessary funding and attention, meaning the system would stay afloat as long as there’s interest.

And boy oh boy, if accessibility can be this seamless, there will be interest for a long time. I’ve seen first-hand the strong but unfocused interest in CD-ROM preservation that’s floating around, and if anyone can jump in and easily play such games, that curiosity will coalesce and explode. We’ll see scholarship and discussion for obsolete works long abandoned, as Rhizome demonstrated with the Theresa Duncan games. Chop Suey, Smarty, and Zero Zero languished for nearly two decades before Frank, Gangitano, and Weil gave them the attention they deserved. Hopefully very soon, with the help of the systems Rhizome developed, we’ll see even more obscure games back in the critical and cultural limelight.

The future – we’re there.

Play and learn more

To demonstrate the flexiblity of the system, I’ve directly embedded the games right below (thanks to Espenchied for the embed code). You can also play the games from Rhizome’s website. For greater context on the importance and relevance of these games, see Rhizome artistic director Michael Connor’s extensive curatorial notes.

Thank you for this in depth review of the event & process!