Peter Gabriel: Eve

In the book accompanying Peter Gabriel: Eve, Gabriel outlines his vision for multimedia as a deconstructive medium – or, as he puts it, a toolkit for examining art. “People can then become part of the creative process in this way,” he says, and he believes his art in particular serves as an effective “vehicle for ideas and emotional content” when broken down and explored. He touched on these ideas in Real World Multimedia’s first CD-ROM title, Xplora1: Peter Gabriel’s Secret World, where he espoused interactive media as a place “to provide a lot of material for the audience to participate in – so that eventually they become the artists themselves and can use what we create […] as stuff to explore and learn about from the inside.”

As his second and final release, Peter Gabriel: Eve stands as the most complete expression of that idea. The game assembles art, sound, print media, and knowledge into a postmodern collage, breaking them into pieces for the player to refashion. Its approach to participatory multimedia fosters a confident exploration of love and relationships, and it would have been stronger if it wasn’t moored to a specific interactive presentation of Gabriel’s music. Gabriel’s songs provide a useful overarching thematic structure, and Eve‘s experiments grow beyond the repeated fallback to the title artist.

Eve opens with an interactive scene of an egg being inseminated. A new, raw world is born from it, resembling the Garden of Eden. As you stumble around, a small, floating light guides you to a hut holding a strange portal. A suitcase falls through; symbols, shapes, and noises spill out, complicating the world as they scatter in all directions. Then finally, out of the now ovum-shaped portal emerge Adam and Eve, who quickly part ways. You are cast out into a desolate landscape, left to follow Adam and make sense of the Pandora’s box of ideas you have unleashed.

The game uses Adam’s search for Eve as a catalyst to examine relationships and social interactions in art through four increasingly complex lenses – Mud, Garden, Profit, and Paradise – each built around the mood and content of a Peter Gabriel song about love. In each section, you explore a series of outdoor vignettes, buildings, and museum pieces based on the work of a different artist who deals in those themes. Most scenes manipulate photography to create vivid, unreal places, always containing a number of interactivities that encourage you to prod the art more closely.

If the description doesn’t make clear, Eve is artsy. To the wrong audience or with the wrong tone, this could read as pretentious, but Eve avoids at least the second problem by the strength of what it mashes up. Gabriel chose the art expertly, selecting some works that evoke the section and others that directly comment upon it. (A few scenes are admittedly too strange to connect, even here. A sequence with a frantic duck holding a key doesn’t contribute much, for instance, though the lighthearted weirdness keeps the game curious rather than ponderous.)

The artistry of Eve is multimedia in a literal sense, in that it combines multiple mediums. It’s also about multimedia and its constructive potential: it knowingly brings those mediums together to amplify their effects, in the hopes that the player will find some personal resonance in unusual combinations of image and sound. After interacting with enough of those different elements – maybe an illustration of an eyeball, a guitar riff, and a quote about mortality – you begin to link their concepts together and attach your own value to them. As Gabriel suggested, the player takes responsibility for discovering meaning through art.

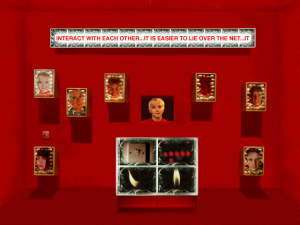

The focus on the interplay between mediums carries through to Eve‘s video testimonials, where doctors, artists, researchers, and other experts speak about the way changing social structures and methods of expression affect how we communicate. The expert interviews, as well as the “lonely hearts” relationship confessionals from average people, are the game’s most exciting and unexpected components. In the middle of the expressive, metaphorical Eve, the interviews provide grounding through evidence and a tether to reality, even when their statements are disagreeable (especially when regressive about gender). Pieces of song and sculpture related to love are effective, but hearing from an 84-year-old priest about how he has seen marriage evolve in his lifetime brings those ideas back to their real implications.

The game mixes art and experience in the same way it plays with mediums: it looks for truth in the collision between those contrasting emotional and sociological approaches to its subject matter.

(Eve‘s substantial art book – yet another medium! – includes extended discussions with the featured artists and experts to supplement the experience. If you can obtain it, reading the book alongside Eve is highly recommended and will deepen your appreciation of what Real World Multimedia assembled.)

As Eve progresses, its messages become more complex and less clear. The game’s hint guide brags that “[a]s the world evolves so do the themes of EVE,” and this bears out. The first group of confessional videos shows people talking about what they look for in a romance, a heartfelt topic that only lightly touches on the practical challenges of companionship. The accompanying Mud area is fittingly a world in its early, primordial stages, mostly composed of rocks and outcrops (and an odd bit where you smash lawn gnomes). As life creeps back into the world, you next visit the Garden, a more baroque setting, to read poetry while statues whisper about “God and DNA.” When you return to the Human Relations Room, the “lonely hearts” interviews feature the same people as before wondering whether lying to a loved one is okay.

Eve doesn’t assume to have answers to these increasingly tricky relationship questions. By throwing together so many varied, rich, medium-crossing items, it smartly lets players composite their own reactions.

If the game offers any planned space for a cathartic reaction, it does so through the Interactive Music eXperience, a multimedia music video toy for Peter Gabriel’s songs that caps each section. In the IMX, many of the backdrops, art pieces, and sounds you encountered act as instruments for performing Gabriel’s music. It ties your personal connections with the ideas and art back to the songs that provided the game’s loose structure, and as a culmination of the experience, it adds greater meaning to both.

And yet, Eve‘s thematic explorations don’t need to revisit Gabriel’s music again. By casting much of the game in a supporting role behind Gabriel’s songs, Eve lessens its content and impact more than enhances them.

To be clear, the IMX works remarkably well as a form of interactive musical expression, and Gabriel’s music makes a useful framework for considering love and sociability. But Eve hits on ideas bigger than his music. An interactive music montage can’t contain the game’s strongest, most resonant material, and large portions of Eve are hamstrung by the need to dangle IMX rewards.

Significant portions of Eve‘s art interactions asks you to clicking the correct objects on-screen to earn new IMX instruments. For the sake of rationing your rewards, the game limits how many times you can interact with these scenes in one sitting. These outcomes are essentially random, so Eve effectively just arbitrarily restricts your closeness to the art to drum up Gabriel’s interactive music. The game doesn’t need prizes or guessing games to encourage worthwhile interactivity with its scenes; segments throughout the game, especially those set in virtual art galleries, present compelling interactive installations related to relationships without factoring into the IMX or following its constraints. The most unique parts – the experts and lonely hearts – can’t fit into the IMX at all, but the game still prioritizes the music tools anyway.

In fact, whenever the game redirects its focus to Gabriel exclusively, it backs away from those stronger thematic connections. On a few occasions, you can control a live-action Peter Gabriel in a confined space as he dances to and performs his songs. Like the IMX, this showcases musical performance with a new interactive dimension, but the reversion to Gabriel himself doesn’t take advantage of Eve‘s expanding scope.

Peter Gabriel’s music should have been woven more deeply through the fabric of Eve instead of jarringly brought up once in a while as a puzzle hook and an end-point. Maybe specific verses or passages could have appeared more prominently in relevant scenes. Gabriel’s songs bind the game together, and confining them to the Interactive Music eXperience not only distracts from the rest of the incredible multimedia work but devalues the music’s importance to Eve‘s ideas. An image of Gabriel as Adam, wandering with his suitcase, recurs through Eve, and unlike the performance areas, he clearly belongs in the world. The game needs more of that Gabriel.

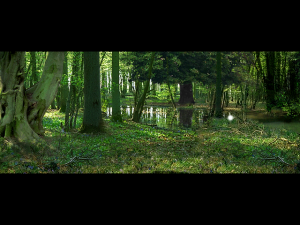

This idealized version of Eve does finally show up in the final segment, Paradise, where your exploration ends. You return to the Garden of Eden. You have no instruments to collect or songs to perform. All that remains are strains from Gabriel’s ethereal album Passion and small puzzles that guide your progress to the ending at the tree of life. The music charges Paradise with a sense of spiritual unity, a symbiosis with the world reinforced by the naturalistic art of Nils-Udo. You light candles that drift down the river, and voices from earlier interviews echo in the background to remind you of the accepted social dilemmas underlying this peace. We last see Gabriel as a reflection in water, lingering as the conductor of Eve but never dominating the moment.

It’s powerful, and it’s perfect. Everything works in harmony. The rest of the game, with its preoccupations, never sticks the landing quite as well.

Misfocused as it may occasionally be, Eve‘s collection of interactive multimedia art raises provocative, unresolvable uncertainties about relationships – and demonstrates the viability of its format for that sort of inquiry. Peter Gabriel put Eve together, but the game successfully hands players the responsibility to form connections about the ideas for themselves. For a topic as conflictingly academic, spiritual, and deeply personal as how we interact and love, Gabriel wisely broke down the art and ceded control – and he should have let it go more often.

Trivia!

Peter Gabriel: Eve was originally intended for release in 1996, but as Billboard reports, the bottom falling out of the multimedia CD-ROM market (especially for musicians) led to a delay and multiple changes in publishers. Although Eve was Gabriel’s last headlining title through Real World Multimedia, it wasn’t his last appearance in games: he later partnered with the Myst adventure series, which he admired, for a string of cameos, most notably providing the voice of a spirit guide in Myst IV: Revelation.

This is the kind of article that I love. Weird, not quite games, not quite videos, attempts to create something different that sort of fell out into the market and were never seen again.

A realização deste site é importante, pois a partir daqui é possivel verificar toda a evolução dos jogos, bem como a interação com os mesmos.

É possivel assim prececionar a evolução que os jogos tiveram até aos dias de hoje.

Este jogo demonstra justamente as primeiras experiências no ramo da interatividade.

This is a form of art that it will never have a label. It´s not a videogame neither a video that gives us a beginning, middle and end. It´s a sandbox where we can create our own path and world. It´s the most form of interaction that we could have with a multimedia content. The story it´s never linear, every path we take leads to a different consequence.

É um bom exemplo que relata uma das 1ªs experiências com interatividade e, por consequência, todo o entendimento da evolução que o multimedia teve até à atualidade.

A junção de vários tipos de arte é bastante positiva no desenvolvimento deste tipo de produtos.

A partir deste site posso ganhar uma percepção da evolução dos jogos e todo o conteúdo que nele está inserido.

A partir deste texto consegui perceber a diferença da interação de ” ontem ” para os dias de hoje.

This project was a first take at something we call “interactive vídeo”. However, has the article says, it was nothing more than an experience and probably to advance for the time it was developed. If it had a better story and company supperting it, it would have been more revolutionary and know today

Hello!

I was playing it a lot 20 years again. I want to buy it to have it and play it again. Please help!

Can you please tell me it can be played on iOS ?

Thank you in advance!

Mick

Perhaps if we insist on it to SCUMMVM developers they might integrate this one. And Xplora.

https://www.scummvm.org/

Great writeup – THANKS for this!

One correction. “Eve” wasn’t Real World Multimedia’s last title. That was “Ceremony of Innocence” – a brilliant interactive adaptation of Nick Bantock’s “Griffin and Sabine” trilogy. “Ceremony” is a masterpiece of interactive design and experience. Flat out brilliant…

Hi Jim, and thank you!

That’s true about Ceremony of Innocence; I’ve been wanting to get to that one! I meant that this was the last Peter Gabriel title from Real World, but that’s a little ambiguous since it was his company, so I changed the post slightly to say it was his “last headlining title.”