SimHealth

In a 1999 interview, Maxis co-founder and SimCity designer Will Wright cautioned against taking his company’s simulation games too seriously. “Many people come to us and say, ‘You should do the professional version,'” Wright said. “That really scares me because I know how pathetic the simulations are, really, compared to reality. The last thing I want people to come away with is that we’re on the verge of being able to simulate the way that a city really develops, because we’re not.”1

And yet, Maxis once made the case for the practical value of simulation games with SimHealth. Produced in collaboration with the public innovation non-profit The Markle Foundation, SimHealth was marketed as “a tool for national debate” rather than a fun game. That public service goal is a departure from the playfulness of the rest of Maxis’s titles: it feels more clinical, no pun intended. SimHealth takes the freeform discovery of the Sim series and channels it into something informational, and it reveals the strengths and limitations of games as hands-on learning tools for tackling hot-button issues.

History and Maxis Business Simulations

SimHealth was developed by Thinking Tools, Inc., a company that used to be part of Maxis, when it was known as Maxis Business Simulations. Thinking Tools president John Hiles had a background in complex behavior modeling, and when his team joined Maxis, they wanted to combine their expertise in simulation design with Maxis’s fun, engaging game interfaces. Together, they made simulation programs for businesses, using the aesthetics of SimCity and carrying the Maxis brand name. These games allowed workers to learn about the dynamics of their industry by experimenting in a playful simulated environment, much like a Sim game but with a more serious model underneath.2,3 As Maxis Business Simulations, they produced the oil refinery simulator SimRefinery for Chevron staff and explored potential titles like SimPower for other groups.4,5

In 1992, The Markle Foundation approached Maxis to see how a business simulation game like this could be applied to a public policy issue. President Bill Clinton had just been elected and planned to address health care reform as one of this top goals, and The Markle Foundation wanted to fund a game that examined the impact of the national health care system. Like Maxis’s other business titles, they wanted to target a specific professional audience that could learn by prodding a model. In this case, that audience was policymakers, as well as the general public.3,6

As simulation games became a larger part of professional life,7 The Markle Foundation hoped to use a game as an accessible tool to guide discussion around a complicated, soon-to-be-heated political topic. SimHealth wouldn’t provide realistic answers to America’s health care system, but its systems would “enlighten people on the complexity of health care reform” in general.8 “If people think the game is fun and interesting,” The New York Times quoted Markle Foundation president Lloyd Morrisett saying, “we will try it elsewhere, perhaps with budget policy, welfare reform or the environment.”9

Playing SimHealth

The game opens with a short narrative to ground the subject. After a car accident leaves you with an enormous hospital bill, you decide to run for office to address the cost of health care. You win some position of extreme power that lets you control all national health institutions, public and private (an exaggeration for the sake of the game’s argument), but your focus stays on how you can help your community. You not only want to bring health care costs down but also to stick to the beliefs that got you elected.

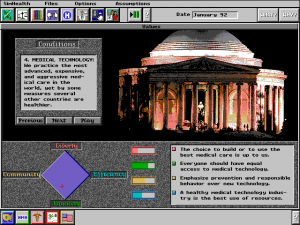

Before you can set policy, SimHealth asks you about your political beliefs and goals to see how your preferred health care system would align with different ideologies. The game judges you not for the merits of the system you enact but for whether you can achieve it within your stated ideals; every two years of game time, an election holds you accountable for how closely you’ve reached your promises.

The game maps your beliefs on different topics onto a political compass, a chart that pinpoints where your ideals lie between individual freedom and community-focused equality. The compass keeps you on-track to reach your desired health care system, allowing you to discover the steps necessary to reach your ideas and judge the effectiveness or success of the results for yourself. Measuring political positions on a spectrum is a flawed over-simplification, of course. Liberty and equality aren’t necessarily opposed concepts as the game presents, and the compass’s dichotomy between community and efficiency – meant to represent beliefs about property and resource allocation10 – seems especially dubious. It’s something to measure against for the game’s sake, but the reliance on the compass calls SimHealth‘s potential accuracy and applicability into question.

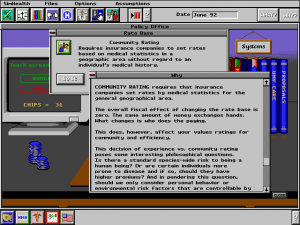

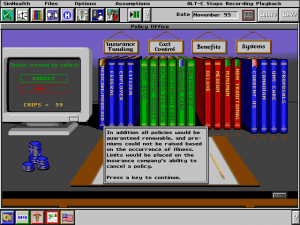

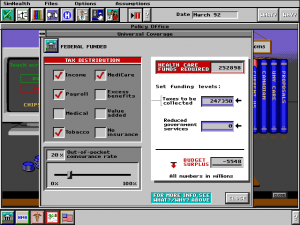

Once you’ve outlined your beliefs, you can start revising the country’s policy. You have a limited amount of political capital (represented as poker chips) to spend on changes to your system; they replenish as the country’s policies move closer to your place on the compass. You can make sweeping reforms, like nationalizing the insurance industry and capping hospital growth, or find smaller adjustments like tweaking coordinated care plans and rebalancing tax logic of existing underlying systems. You might also incentivize alternative medicine or revise malpractice law. New medical devices and drugs will occasionally force you to reconsider coverage levels.

These exhaustive options cover nearly every potential health care proposal. To help you navigate this, each screen includes “What” and “Why” buttons explaining what you can adjust and how it will affect national health care. If you lose track of how the pieces fit together, the game also contains flowcharts showing how doctors, insurers, and the government interact under different health care models. In addition to letting you pursue your own fantasy policy, the game allows you to select from a handful of real health care policy proposals to see what effects they might have – with helpful, lengthy descriptions of their policies, rationale, and room for flexibility. The level of explanation is both necessary and extremely helpful.

Like other programs by Thinking Tools (based on video footage of TeleSim and TransPort),10 SimHealth plays more indirectly than usual Maxis titles. You aren’t constructing buildings; your changes are indirect, affecting the community over time. (This lessens how much you can personalize the game, probably a factor in the game’s detached, academic vibe.)

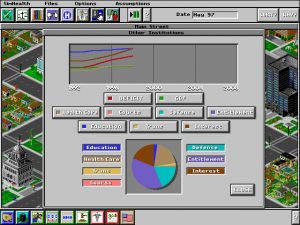

The game shows the effects of your actions in graphs, and it visualizes them through the buildings in your community. Reducing tax money spent on health care without adjusting taxes might improve the condition of the local police station, for example, and higher out-of-pocket expenses will turn a residential neighborhood into a shantytown covered in weeds. Or you can peek into a cutaway of the town’s doctors’ offices. If you change too much at once, the system might go into shock and experience more drastic changes; gradual alterations are easier to track and safer to the community’s well-being.

Seeing your actions slowly, demonstrably transform the state of health care is far drier and mathematical than growing a city, but the experience is deeply satisfying and educational for those interested in witnessing real impact. Lines representing hospital waiting time and admissions at specialized clinics move as the patient experience evolves. Pie charts compare how much citizens spend on their health versus food and housing. Since SimHealth only evaluates how closely you follow your ideology, you can use any of these metrics to gauge your success. If you only want to increase profits for hospitals, the game lets you pursue that horribly misguided dream.

SimHealth recognizes, given its hot topic, the need to be open about the models it employs. Hiles reasoned that if the game had some disguised political motive or refused to disclose its possible biases, experts and the public alike would “push it over into a ditch.”10 To this end, the game includes a menu of assumptions, revealing the projections and presumptions behind the simulation. You can tweak these to figure out if your proposed health care system works with slightly divergent logic. These settings need considerable patience to sift through, unfortunately, and the game would benefit from an easier way to set different groups of assumptions like you can with pre-baked policy proposals.

The game has a deeper weakness in the tension between achieving your ideological goals, based on your political compass, and seeking good policy. By tying your political capital to how closely you can match your ideal health care system, SimHealth discourages you from experimenting with other solutions. Thankfully, you can switch off the game’s accountability, so you can try a real-world proposal that differs from your own views or just run ripshod over the health care system and see what happens. You can still check your compass to see how your policies align, and periodic health industry conferences will alert you to professional recommendations.

But the game wants to bring user ideals into the simulation – or as the Brookings Institution’s Joseph Epstein explains it, testing your own beliefs on the health care debate “by facing a certain amount of explicitness.”10 When played as a mirror of your own politics, SimHealth needs the formal feedback of capital and elections to keep you focused.

Impact, reception, and legacy

With SimHealth, Maxis set their sights big. They wanted the game to influence the national debate over health care and targeted lawmakers at the highest level. The game debuted in November 1993 at a press conference on Capitol Hill,11 and Maxis distributed the game to the White House and Congress.9 According to Maxis developer Mike Perry, even Chelsea Clinton played it.12

Maxis’s foray into politics opened the simulation genre to unprecedented attention and scrutiny. SimHealth weathered its first impression well, receiving positive early buzz over how games could represent the future of policy debate. Jeff Eller, a spokesperson for President Bill Clinton’s health care reform task force, had faith that the format “could serve policy professionals as well as amateurs by forcing those with different views to examine their assumptions.”9

Despite this promise, SimHealth was unsuccessful in either sales or impact. A “serious game” would have been difficult to market to the public, and the technical hurdles of running a computer game in the mid-90s13 surely contributed to its unpopularity among lawmakers, a group not usually known for computer literacy. Sales estimates hover around 50,000 copies shipped.6,14 SimHealth did reportedly find a home in health administration academia,6 but that was a far smaller and more insular success than Maxis, Thinking Tools, and The Markle Foundation had no doubt hoped for.

The Markle Foundation’s Edith Bjornson admitted that “the effect of the game on the quality of the debate was not on the scale we would have liked.” Still, Bjornson praised the game’s accomplishments, calling it “intellectually honest and what education should be.”14

This is SimHealth‘s great controversy. Beyond whether the game was successful, its reception raises larger questions about the value of simulation games and their role in the public sphere.

In a 1994 editorial about political budgetary models, Paul Starr, a senior health care policy advisor to President Bill Clinton, savaged SimHealth as faulty and misleading. He noted a range of problems that damage the game’s practical application, from the political compass concept to its understanding of the health care system to mistakes translating real health care reform proposals into the game’s choices. “SimHealth contains so much misinformation that no one could possibly understand competing proposals and policies, much less evaluate them, on the basis of the program,” Starr said. “Once the novelty of making health policy into a game has worn off, I doubt SimHealth will hold much interest. It certainly has no value in assessing health care reform.”15

More than the specific accuracy issues, Starr was alarmed by the idea that players might interpret simulation games like SimCity and SimHealth as legitimate, scientific projections of policy. He mentions playing SimCity with his daughter, who accepted the game’s favored urban planning strategies because “‘[i]t’s just the way the game works.'” Starr also considered SimHealth‘s assumption menu too impenetrable to indicate where the game might lean. Simulation games can be “seductive,” he argues, and if they fail to inform about the tendencies and limits of their models, players may put undue faith in the teachings of a closed system they cannot scrutinize.15 In an article for The American Prospect, Sherry Turkle called this the “abdication of authority” to a simulation,16 and it is exactly what Will Wright feared.

Some of Starr’s criticisms are legitimate but perhaps overstated from a policy expert’s perspective; SimHealth is, after all, concerned with the contours of the issue,8 not the exactness that the president’s health care advisor might want. But the fact the Starr had those concerns proves that a misinterpretation of SimHealth‘s goal is a real problem. Games are a seductive medium – that was the basis for Maxis Business Simulations – and the appeal of a concept like SimHealth giving you direct control of the health care system distracts from its mission and its attempts at transparency.

SimHealth makes every effort to clarify how it does and doesn’t reflect reality. The manual emphatically states this in its opening pages:

SimHealth won’t […] eliminate the need for everyone involved in the national health care system (which is everyone) to learn everything they can about it and be an active participant in the coming changes [or] predict the future results of a particular policy or system. […] SimHealth will show you the big picture of the health care system, and give you an understanding of how all the diverse aspects of health care are interrelated. […]

Before you accept anyone’s claims that SimHealth proves his or her point, be sure to check the underlying assumptions. And when you claim to have proven your own point, be ready to back up your own assumptions.17

The game even offers a disclaimer when choosing a real health care model that “SimHealth cannot predict the future.”

Is that enough? If you claim that a game has predictive modeling value, is it possible to dial back how you depict that without discrediting it? John Hiles addressed this in a talk at the George Washington University, where an audience question about how SimHealth would forecast a recent Medicare reform proposal showed confusion about how the game worked, even as the creator explained it. Hiles compared SimHealth to a hurricane simulator. It can’t predict whether a hurricane will hit Florida in a year, but it can show what “contingencies” might arise if a hurricane did hit the state.10

With this level of context and research, what non-expert would separate SimHealth from the real thing?

That’s a very fine distinction for marketing a computer game, especially when it comes from famous simulation game developer and it bills itself as a public policy tool. As Will Wright’s concerns1 allude, Maxis had enough problems clearing this up with SimCity, which much more obviously puts entertainment first. SimHealth, on the other hand, includes real policy proposals from actual lawmakers. Developer assurances aside, the game presents itself as more than just a hurricane simulator: it sells that idea that it can tell you what will happen. Educational simulation games have arguably still not escaped this perception issue.

Joseph Epstein hoped that games like SimHealth could be the future “laboratories for social science research,” tools experts could use to play with policy proposals.10 That future could still exist, but it relies on experts who understand the limitations and purpose of simulation models.

Markle Foundation president Morrisett lamented that the game should have been geared primarily toward the public rather than policymakers to reach the audience that would have benefited most from its ideas,6 but this would have required a significant retooling of the game’s presentation to convey its strengths and weaknesses more clearly. Without that, SimHealth remains a serious game left behind, an inventive, flawed, semi-professional-level stab at fitting national politics into the Maxis mold.

For more about SimHealth and simulation software, read The Obscuritory’s interview with the game’s director, Thinking Tools president John Hiles.

Trivia!

SimHealth‘s title screen was painted by Bruce Ariss, an artist who created public works murals during the Great Depression. Ariss was selected to evoke the enormous scale of New Deal programs and juxtapose it with the wide-reaching scope of health care reform.10,18

(This article was lightly revised on April 28, 2020.)

References

1. Ito, M. (2012). Engineering Play: A Cultural History of Children’s Software. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 153. Retrieved from http://www.ebrary.com

2. Siegmann, K. (1993, March 5). Computer Games Get Real – Simulations let companies solve complex problems. The San Francisco Chronicle, p. D1. Retrieved from http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0EB4F4E6C7A6992A?p=AWNB

3. Gunn, M., & Hiles, J. (1994, July 22). Tech: Technology and Health Care. Tech Nation. Recording retrieved from https://archive.org/details/RTFM-Tech-940722

4. Barr, C. (1993, June 15). Businesses Play War Games. PC Magazine, 12(11), 31. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=jMKfH6i9OcYC&pg=PA31

5. Booker, E. (1993, March 8). Simulations growing up. Computerworld, 27(10), 35. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=ujcOExZ3Ey0C&pg=PA35

6. MacPherson, P. (1995, Dec. 20). Playing the game. Hospitals & Health Networks, 69(24), 82. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/215311773

7. Burgess, J. (1993, April 12). The Realities of Simulations. The Washington Post, pp. 19, 30. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/140875633

8. Jones, D. C. (1994, Aug. 15). Simulation software tackles health care reform. National Underwriter, 98(33), 5. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/228457061

9. Passell, P. (1993, Dec. 24). Pac-Man It’s Not. The Future of a Presidency and U.S. Health Care, Maybe. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1993/12/24/us/pac-man-it-s-not-the-future-of-a-presidency-and-us-health-care-maybe.html

10. Hiles, J., & Epstein, J. (1995, Oct. 20). Lessons learned from SimHealth: the promise and limits of health policy simulation [VHS], Special Collections Research Center, Estelle and Melvin Gelman Library at the George Washington University, Washington, D.C.

11. Mitgang, L. D. (2000). Big Bird and beyond: the new media and The Markle Foundation. New York: Fordham University Press, pp. 258-259.

12. Perry, M. (2016, July 28). One of us old Maxis folks should tell the story of when the secret service called our tech support in 1993 to help Chelsea play SimHealth. [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/mike_perry/status/758856064645214212

13. Mossberg, W. S. (1994, Jan. 13). Personal technology. Wall Street Journal, eastern ed., p. B1. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/398359124

14. Angus, J. G. (1994, Aug. 7). Sim-Ply Fascinating — Simulation ‘Games’ Offer Real Educational Opportunities. The Seattle Times. Retrieved from http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19940807&slug=1924051

15. Starr, P. (1994, Spring). Seductions of Sim: Policy as a Simulation Game. The American Prospect. Retrieved from http://prospect.org/article/seductions-sim-policy-simulation-game

16. Turkle, S. (1997, March-April). Seeing Through Computers: Education in a Culture of Simulation. The American Prospect, 31, 76-82. Retrieved from http://web.mit.edu/sturkle/www/pdfsforstwebpage/ST_Seeing%20thru%20computers.pdf

17. Bremer, M. SimHealth: The National Health Care Simulator: User’s Manual. Orinda, CA: Maxis, pp. 6-7.

18. Bremer, p. 30.

Genuinely fascinating. The idea of trying to provoke public debate through video games in a way that doesn’t have any particular bias is something that on the surface sounds interesting, if a little unlikely.

Now I understand a little better why all your reviews are so well written (and uncharacteristically so for the genre of journalism).

Did you go to Amherst or something? Or a similar school that makes you output many pages of writing per week? 😉

Thanks Gibbous Moon! I’m a librarian, so I love getting really deep with sources and looking into all their connections.