GADGET: Invention, Travel, & Adventure

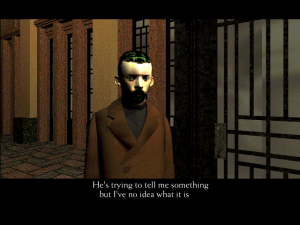

GADGET is a nightmare. I don’t mean that in a pejorative sense. It very much has the qualities of a nightmare. The game ambles in repetitive and disorienting directions, chained together by irrational, non-sequitur plot developments. Imagery is bold and surreal, punctuated by out-of-body experiences and blurry detail. It is unsettling.

Developed by Japanese studio Synergy Inc., GADGET: Invention, Travel, & Adventure lacks much of the mechanical structure we associate with games. There is little meaningful interactivity. But because the experience is so un-game-like, so rigid and suffocating, it evokes genuine confusion, terror, and discomfort. This is not a game that will make you jump, but once you’re deep within GADGET‘s pseudo-Soviet web of intrigue and conspiracy, some gut reaction will tell you that it should not be happening.

GADGET sends players to a surreal, expressionistic Eastern Bloc country where a group of rogue scientists predicted the impending end of the world at the hands of a comet. You are employed by the mysterious inspector Slowslop to hunt down Horselover (yes, really), the leader of the fringe scientists. With little fanfare, Slowslop hands you an old photograph of the scientists and dispatches you down the Grand Central Railway in search for any clues about what the scientists may be planning.

And clues you do find. The road to Horselover is riddled with weird happenings and red herrings, like a mysterious child who steals your luggage and a Sputnik-esque satellite that broadcasts images from the future. Half the characters you meet insist the comet is a lie and that Slowslop is a disreputable pervert, while the others ramble about self-mutilation and plead that you believe the scientists. Only about a dozen or so people exist in the world of GADGET, and each seems to follow you around with extreme suspicion. Slowslop also behaves erratically: he will randomly appear along the Grand Central Railway and update your assignment, at one point telling you to stop following Horselover and simply conduct surveillance on train passengers. Once you finally meet Horselover, the story turns to a race against time as the scientists attempt to build the Ark, a spaceship from which to escape the imminent apocalypse.

The plot hinges on Sensorama, a kaleidoscopic device made from scrap metal that the scientists supposedly use to control their subjects. Everyone in GADGET has an opinion on Sensorama, but it is very unclear what it actually does. The scientists insist that the device “draws out latent powers,” while skeptics insist that it is a mind control device used to create legions of followers who will cripple the world with fear over the comet. A film found within the Museum of Science supposedly elaborates on the function of Sensorama, but it’s just a contextless clip of a man convulsing in a chair. When you come face-to-face with Sensorama at the end of the game, it’s clear that the device is bad news – but its specific function remains a mystery.

Needless to say, it’s bewildering, and worst (or best?) of all, nothing is ever explained. It appears that the scientists are connected via Sensorama and the Ark to an evil dictator, but this third-act twist just raises further questions. What does the dictator want with these devices? To take over the world, maybe. Is there actually a comet? It’s uncertain. Were Horselover and Slowslop collaborating the whole time? Possibly, but for unclear reasons. Who was that weird boy? Apparently Slowslop’s true form. Were those other suspicious people in league with the scientists? Sure, why not. There’s no wrap-up; you are subjected to Sensorama, presumably rotting your brain, and the little boy flies away in a zeppelin.

GADGET toys with themes of memory and control, but they (intentionally?) lack any cohesion. It’s frankly liberating to play a game that never attempts to clarify its baffling story, but you’ll still exhaust yourself tracing the various plot threads before it becomes clear that they’re all dead ends.

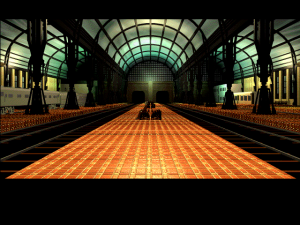

The dangling narrative only works, though, because of how the game presents and builds the bizarre, inscrutable Grand Central Railway.

In GADGET, you have very little control of your surroundings and circumstances. At each stop along your journey, characters from the game’s limited cast recurringly appear in too-convenient places and coerce you along a particular path. You are usually restricted to this one direction even when alternative paths exist. In the opening section of the game, for instance, you are told to walk down a hallway towards an elevator bay, but you cannot walk back the other way. Later, your train’s conductor insists that you disembark at a way station only to ask you to reboard immediately. At a point when you finally take control of a plane, a symbol of freedom of movement, your character immediately grounds it and gets back on the nearest train. Once in a while you don’t get to walk to your destination; many sections of the game are replaced with blurry black-and-white cutscenes automatically sending you to your destination. Sometimes your movement is just implied through disembodied, abstract cutscenes, almost like establishing shots on a TV show.

When you do get to explore it, the world of GADGET is almost entirely abandoned and sterile. The first half of the game sends you to the massive and garish East End train station, but once you arrive there, the terminal is deserted. The only people you ever encounter are a handful of plot-important characters standing in odd places to point you towards a specific door.

In all these cases, the player is robbed of agency. Much like game’s ubiquitous trains, you are always moving forward on a fixed track. There is never any choice in what you will do next and rarely an opportunity to explore on your own terms. This feels so very, very uncomfortable.

Different circumstances could have made this look like a cop-out to limit the size of the game. But in GADGET, it feels like a large-scale gaslighting attempt. In a telling example, the few items you receive fit perfectly into unusual slots in your suspiciously acquired inventory suitcase. Was this whole thing a setup? Is that why it’s going so smoothly with almost no hangups? Why are the only people in this world directly concerned with my mission? And why am I going along with them? It’s too weird that every single person along this railway would be trying to drive a single person insane. Considering all the focus on the ambiguous Sensorama, this might even be a depiction of mind control.

The whole endeavor just feels wrong. If you’ve seen The Shining, you’ll remember that the Overlook Hotel has an otherworldly and hostile aura despite much of the movie lacking overtly supernatural elements. GADGET comes across the same way. Each second of the game is filled with paranoia and dread. Every cryptic story about mind control, every abandoned and unexplorable railway station, and every allusion to an apocalyptic future builds on a suspenseful and overpowering darkness that is never resolved and ultimately leaves you with empty uncertainly. A rhythmic, discordant soundtrack teams up with the blocky and unsettling visuals to undercut even the seemingly normal scenes, throwing their tone into chaos. Nothing in GADGET feels safe – usually just because of its aura of disorientation.

That aura is what sets GADGET apart. On paper, GADGET‘s story and linearity sound alienating and unenjoyable. In practice, it thrusts the player directly into that alienation and asks them to share in the confusion. This is a game largely devoid of puzzles or substantial gameplay (save for a single maze at the end), but by stealing these opportunities for input from the player, it creates a distant, hands-off world that always sits just outside the cusp of understanding. There is a strong possibility that this atmosphere is an accidental result of terrible craftsmanship. But after multiple playthroughs, the Grand Central Railway still defies and intrigues me, and that’s a hallmark of transcendent world-building.

The expanded GADGET-verse

GADGET was apparently successful enough to elicit a number of spin-offs, including:

- Inside Out with Gadget, a lengthy behind-the-scenes art book the elaborates on the world of GADGET

- Resonances of Gadget, an expanded soundtrack

- Gadget Trips: Mindscapes, a video art project based on Sensorama

- The Third Force: A Novel of Gadget, a sequel novel that reportedly clarifies many questions about the game, including the nature of the comet

- GADGET: Past as Future, a four-disc remake that delves into the plot in greater detail

I’ve had the pleasure of experiencing some of these first-hand, but they’re about as weird as you’d expect. Past as Future is unusual in the degree to which it is nearly identical to the original: the cleaner edges (smoother transitions, for instance) wipe away some of the original’s mystique, but scene-for-scene, it remains the same experience. This version was at one point available for iOS under the name iGADGET HD, but it sadly now appears unavailable.

Trivia!

GADGET seems to have picked up a small cachet with filmmakers in the 90s. Guillermo del Toro, acclaimed director of Pan’s Labyrinth and Pacific Rim, considers GADGET a personal favorite game and an important influence on the dark industrial film aesthetic of the late 90s. David Lynch also said GADGET “delivered an immense experience” and briefly partnered with Synergy to develop a similar game of his own, titled Woodcutters From Fiery Ships, which unfortunately fell through. Could you imagine?!

The name Horselover could be a reference to Horselover Fat, Philip K. Dick’s alter ego in the seriously weird VALIS

That’s the best (and, well, only) explanation I’ve heard. It makes sense since both the game and that book involve hallucinatory images. Thanks for pointing that out!

Hi, this is a few years late but I only just discovered your blog this past week and this game sounds like it’s really down my alley!

Is there a way to play it on a Windows 10 PC?

Hi! I hope you find it interesting, as long as you’re okay with something very purposefully unsatisfying.

To play the game on a Windows 10 PC, you’ll need to use DOSBox, a program that can emulate an earlier version of Windows. See the Resources link at the top of the page for more info about, and please feel free to contact me if you need help setting it up!

Hey Phil, I just bought a copy of Gadget on Amazon recently, but I run Windows 10 and I’ve never had to set up DOSBox before. So I was wondering, is this tutorial up to scratch? – https://www.howtogeek.com/230359/how-to-install-windows-3.1-in-dosbox-set-up-drivers-and-play-16-bit-games/

Thanks in advance.

That guide does a pretty good job! One thing is that I’d recommend keeping the resolution to 640×480 since this is what fullscreen Windows 3.1 games used, both to avoid any technical problems and to stay closer to the intended experience.

Of course, “horselover” is simply the literal translation of “Phillip” from the original Greek (and “fat” the literal translation of “Dick” from the original German)

I have very little to add to your review. What a game! I won’t claim to understand authorial intent, but I’m blown away by how deliberate everything is. The plane you can use for a short time, the “symbol of freedom of movement” you ditch immediately, has an oppressively tiny windshield. The boy steals your suitcase, with its obvious contents of notebook, spare shirts, toiletries etc. and replaces it with an identical suitcase that contains a binoculars-like device and empty indents that conveniently and suspiciously fit the other strange devices you’ll collect later in the game (I’ve *just* finished writing this, and out of nowhere the game presents me with my notebook – lost with the stolen suitcase – where a formerly blank page now has a list of the strange devices, in my own handwriting…). I’ve never played anything like this. No game that came before or after it can compare even remotely

By the way, if anyone else is getting errors like “Director Player Error – The Quicktime or AVI movie could not be opened”: install or update Quicktime. The latest version supported by Windows 3.11 is Quicktime 2.12, which you can find on many abandonware/retrogaming websites. The installer may ask permission to uninstall the Quicktime version installed by GADGET: go ahead and do it

And what about the way you’re “accidentally” first introduced to the Sensorama, when you catch a glimpse of it in the hotel room across the hall from yours, where the door has been “accidentally” left ajar? And the bellhop kicks you out with the transparent lie that the room is being renovated? It plays out almost exactly like a nightmare I had many years ago. Crazy. Man, I can’t stop thinking about this weird game

It can be easy to describe a game as being like a nightmare (I do that all the time), but it really applies to GADGET! The way that you’re led around and the game slides between locations, like the binoculars sequence before the museum, which still haunts me.

If you liked GADGET, I’d recommend trying Paratopic. It also plays around with a shifting sense of location, loss of agency, and the vague malevolence of travel.

Does the Windows 95 version compare favorably to the PS1 version? The latter is simpler to emulate (and also gamepad friendly), so if it is identical it is probably preferable.

The PlayStation version is the remake, GADGET: Past as Future. I haven’t played the PS1 version, but it’s probably the same apart from lower resolution. Windows emulation can be difficult to set up, and if the PlayStation version is easier for you, go for it! (In general, I feel like older adventure games with cursor input are better to play on a computer with a mouse, but if you’re comfortable using a gamepad, that might be okay.)

I’m sure I read about this in an early edition of Wired UK (not the recent re-boot)…

I believe the novel tie-in was written by none other than Marc Laidlaw, who would later be most famous for writing the story of Half-Life & Half-Life 2 and its episodes, apparently he reused some elements in Half-Life’s story from his tie-in novel for Gadget

https://combineoverwiki.net/wiki/References:Marc_Laidlaw_emails#On_connections_between_Half-Life_and_his_books

That’s wild, thank you for sharing! I can totally see how the G-Man is similar to Slowslop… what a connection!

You’re welcome! Yeah, I believe Laidlaw by his own admission had been inspired to get into videogames (he had been an up-and-coming science-fiction writer before that, of course – perhaps one reason why Half-Life 1 & 2’s story somehow felt a bit more compelling compared to the usual threadbare plots of FPS games) after he had played Myst no less.

In retrospect, I can see a lot more similar vibes…mysterious and somehow alien feeling Eastern European city transported by rail, yeah that definitely bled into Half-Life 2 in the form of City 17, and the beta version of HL2 sure had a lot more uncanny and eerie elements.

*similar vibes between Gadget and Half-Life 2, sorry forgot to add that in