Fact, fiction, and fear in Ghosts and Weird

Ghosts and Weird: Truth is Stranger than Fiction aren’t exactly educational games. They’re more like those sketchy shows on the History Channel.

There’s plenty to learn in Ghosts and Weird, though not anything you’d hear from a more reputable source. Both these games, created by largely the same team led by producer-director Philip Nash, tell stories about alleged encounters with the paranormal – ghosts, ghouls, hauntings, psychic premonitions, alien visitations, and everything else spooky that somebody ever claimed happened to them. They take folklore, and they blow it out into a larger-than-life 3D world, like a gallery of supernatural curiosities.

This type of immersive encyclopedia was common for a short time in the mid-90s, when publishers were discovering new ways to present information on CD-ROMs, like the virtual museums in Eyewitness Virtual Reality. With The X-Files and the 1995 alien autopsy hoax frothing the public’s interest the supernatural, that made it great subject for a CD-ROM. But in the spirit of a dodgy cable TV documentary about aliens, these two games act like they’re serious informative programs. Is it still just spooky, or is it misinformation?

And can you believe Christopher Lee is here?!

In these games, you are brought to a bizarre, remote location, filled with artifacts from purported paranormal activities around the world. You must learn more about them, which in practice means you walk through rooms and click on different objects to read about them. For a special few objects, the games will narrate the story with pictures, like a reenactment in a documentary.

Ghosts and Weird have their own approaches to the interactive museum format. They end up in quite different settings, each extravagant in their own way, and they find their own methods for contextualizing their stories. Ghosts is a quieter, ghastly affair; Weird is intense and unreal. Either way, they have a touchy relationship with the truth.

Ghosts

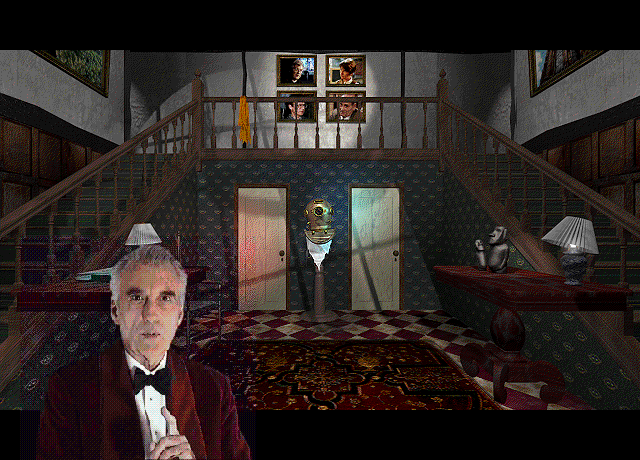

You have arrived at the mysterious Hobbs Manor, where the paranormal researcher Dr. Grimalkin has gathered his life’s work investigating the paranormal for you to inspect. He greets you in the foyer… and he’s played in live-action by none other than horror movie icon Sir Christopher Lee.

For everything else good or bad about Ghosts, Christopher Lee carries the entire game. Every word out of his mouth has gravitas. Even when he’s explaining how to play the game, he makes it sound grave and mysterious.

The game wisely uses him as much as possible. Throughout the mansion, Dr. Grimalkin has placed items relating to real-life ghost stories from England, such as the tale of the Screaming Skull of Bettiscome Manor. Dr. Grimalkin will relay the story of that accursed object to you, going at his own pace, embellishing the script with dramatic pauses and uttering phrases that only he could get away with speaking out-loud. It doesn’t have to be a full story, just a superstition. For a wine glass in the kitchen of Hobbs Manor, Dr. Grimalkin offers a warning: “If you have ever broken a glass whilst drinking,” he says, “you will have experienced an omen… of death.”

Nobody else but Christopher Lee could have made that cheesy line sound genuinely foreboding, but he does it. Come to think of it, nobody else could properly say “whilst” like that either.

Deep in the basement of the manor, behind a ghostly wine rack that doubles as the game’s only puzzle, Dr. Grimalkin materializes inside an oil painting and reveals that he has been dead the whole time; it’s a goofy twist that only works because Christopher Lee has so much charisma. Lee is an asset to Ghosts, a spectacular counterweight to its arch cheesiness.

See, outside of Lee’s ominous delivery, Hobbs Manor isn’t all that creepy. Apart from an occasional low-octane jump scare where an evil face appears in a wall, Ghosts is shockingly calm and quiet. (The few moments when a creepy piece of music swells up are notably the scariest parts of the game. Audio may simply have not been in their budget.) The game tries to wring chills out of real-life testimonials from people who say they were visited by spirits, but their meandering, uneventful stories fall flat.

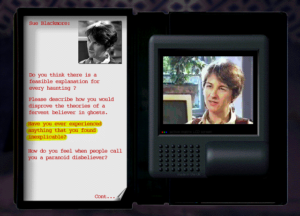

If the real world can’t be as scary as the game needs, it can at least be a source of mystery and debate. Ghosts incorporates video interviews with real paranormal investigators of all shades, from ghost hunters (one of them demonstrates a ridiculous device that he claims is a ghost gun but is actually just a large flashlight) to a priest who studies exorcisms and to Dr. Sue Blackmore, a doctor of parapsychology and a vocal skeptic. The game asks them what ghosts look like or if they believe there will ever be proof that they exist. It’s a smart approach to ground the folklore in the ways that those stories matter to people in the present.

What’s frustrating is how the game puts these experts on an equal footing, the ghost hunter fumbling around with his big stupid flashlight treated as just as insightful as the parapsychologist with decades of research experience. There’s a recurring message in the game about how the truth about paranormal activity can only come to light from “a balance of believers and non-believers,” as if they both have equally truthful arguments.

To be fair, skepticism isn’t fun. The allure of ghost stories is in letting yourself abandon disbelief and accept, for a moment, the stories might be real, that there could be impossible forces at work beyond our understanding. But Ghosts goes a step further by suggesting that science can’t be trusted. That isn’t necessarily harmful in a setting like this, but it’s at least reckless for the game to pretend to be educational.

Because that’s not really what it is. At its best moments, it’s a CD-ROM where Christopher Lee tells you ghost stories. Hell yeah.

Bizarre sculptures. Floating rocks. Unknown locations

Weird: Truth is Stranger than Fiction

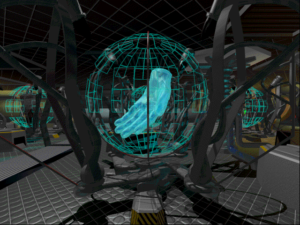

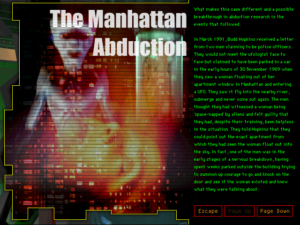

If the star of Ghosts is Christopher Lee, then the star of Weird: Truth is Stranger than Fiction is the secret underground laboratory where the game takes place. The back of the box for Weird promises “3000 screens of extreme weirdness,” and it delivers.

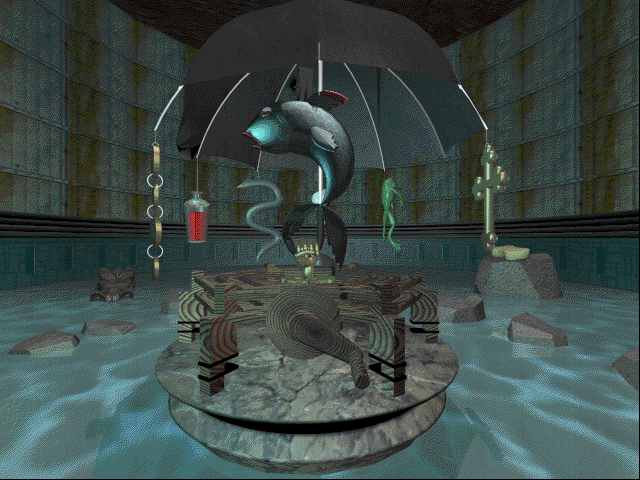

The laboratory in Weird resembles a prison where paranormal objects have been locked away for study, or perhaps for safety. They seem to reach out and transform the space around you when you approach them, bathing the room in colorful light and bizarre imagery. They speak about cryptids and unlikely premonitions of doom, and as you stray further outside, the weirdness intensifies. The aesthetics of this otherworldly location clash with as much coherence as the name of the game suggests, as unexplainable as the supernatural events that seem to have given birth to this anti-logical nightmare place. Inside a rusting chamber filled with water, a gargantuan steel sea serpent rises from the deep, and it raises as many questions about who built this place and why as it does about the reported sightings of sea serpents. What then could possibly be suggested by a massive letter X, carved out of stone, looming over foggy colosseum called the Arena of the Gods? Don’t you want to find out?

Weird is, in fact, weird for a reason. It leverages the extreme scale and surrealism of pre-rendered CD-ROM adventure games to match the outsized, unbelievable nature of urban legends. It’s one of the most outlandish versions of the interactive museum concept, and it begs to be explored.

The game also tries its hand at a few puzzles, one of the other elements of surreal CD-ROM adventure games, to less effect. They’re disconnected from the rest of the setting and mostly relegated to fancy-looking iterations of stock puzzles like Tower of Hanoi and Simon, or at one point an extraordinarily boring maze. They’re a flimsy imitation of the puzzle design in better games, but they serve a purpose in Weird too. Locking anything behind a puzzle at all in this world suggests there are even more terrible secrets that must be kept hidden from prying eyes. It helps build out a setting steeped in the conspiratorial energy that typifies paranoid media like The X-Files or Drowned God.

And yet, it doesn’t have Christopher Lee. Maybe that’s not a fair comparison, but the replacement narrator in Weird lacks the hypnotically malevolent energy that makes Christopher Lee’s storytelling so compelling. Instead, they sound like they’re reading a script. When the narrator describes the theories of how Stonehenge was created, their disinterested, passive voice that does a disservice to the long-standing mystery of that monument – something the game should want to care about! As much as the world of Weird is like a sledgehammer of atmosphere and intrigue, there’s no substitute for a good story.

The game relies more on long paragraphs, accompanied by striking collages meant to the convey the tone of the stories. There are so many things to discover in Weird, yet they actually have less context.

Like its predecessor, Weird is still just masquerading as an educational game. In theory, the game is based on real incidents that have been reported throughout history, but of course a lot of it is bullshit. The game puts on in a slippery, suggestive tone of voice to try persuading you to believe that, for example, mermaids are real. There are video interviews with dubious self-declared experts in fields like reincarnation, and the game repeats poorly sourced rumors at face value, like the legend of Mrs. Agnes Paquet, a woman who claims to have seen a vision of her brother as he was dying. This is a sideshow acting like it’s the Smithsonian, but despite what the title implies (Truth is Stranger than Fiction), the game doesn’t try to contextualize any of this by dragging it into a broader conversation about science or reality. The unbelieveability speaks for itself.

Compared to the investigation angle in Ghosts, it’s not clear what this bizarre place is or why you’re infiltrating it. These are just creepy, weird stories in a creepy, weird place, and honestly, the game is better for it.

A study in spooky

The best point of comparison for Ghosts and Weird might be Beyond Belief: Fact or Fiction, a paranormal television show from the late 90s with the same vibe, hosted by Jonathan Frakes. On the show, Frakes would present re-enactments of seemingly impossible stories, and at the end of the episode, he would reveal which ones were based on allegedly real events. The show tries to challenge the audience to question their understanding of reality with the same needling, conspiratorial voice that Weird uses, yet it still encourages viewers “to separate what is true from what is false” and not to accept the stories at face value.

Ghosts and Weird give lip service to that idea, but they aren’t interested in separating fact from fiction. Actually, they’re not even interested in teaching! Look at how disorganized they are. The in-game encyclopedia in Ghosts lacks the basic navigational tools you’d expect from a legitimate digital encyclopedia, and the exhibits in Weird are mostly randomly distributed between rooms without much of a pattern. These aren’t reference guides to the supernatural.

In both games, the focus is more on discovery, the process of uncovering these unbelievable stories for yourself. The crystallizing moments are when you pick an object off the shelves and Christopher Lee takes you into its sordid past, or when you step out into a vast surreal landscape of mysterious artifacts.

Ghosts and Weird find an unexpected parallel between ghost stories and edutainment: what makes them effective is how they’re delivered. Preferably if they’re delivered by Christopher Lee.

Honestly, I’d love a paranormal investigation show based entirely on scepticism and science, with the “ghosts” turning out to be shit like gas leaks and other perfectly natural phenomena. Basically, a real-world Scooby Doo. :V

Love Christopher Lee, I wonder if anyone has cut together all of his bits from this?

Marginally related, but here’s some videos I put together from The Many Faces of Christopher Lee that I think only I find funny.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X0Wzmjqccow

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwSfzW2ZIA8

If anyone knows of any other interactive/virtual museum CD roms please send them my way