Obsidian

If you wanted to cut to the chase, you could say Obsidian is a game where a computer goes rogue and tries to destroy the world. There’s lots of stories like that, and technically, that’s where Obsidian ends up too, but the path it takes to get there is mind-boggling.

The longer version is that Obsidian is a game where a computer learns how to imagine, where dreams take on dizzying, literal form, and the end of the world is just a chance to reinvent it. Adventure games have a history of packing complicated puzzles into strange places, and using that same format, Obsidian asks the question whether it’s a good idea to dream at all.

Obsidian was one of the last titles developed by Rocket Science Games, a studio with a history of high-budget misfires. Rocket Science made action games that used full-motion video, and although they looked cool for the time, they weren’t well-received. Their previous games, like Loadstar: The Legend of Tully Bovine and Rocket Jockey, sold less than 20,000 copies each,1 which would have hurt less if there wasn’t so much riding on the company.

Rocket Science was supposed to be the future of interactive entertainment. They wanted to be the start of a new digital Hollywood – as so many multimedia start-ups in the 1990s aspired to be – and they sank enormous resources into building up their studio like it was a movie production house. The publicity was electric; Rocket Science made the front cover of Wired magazine in 1994, promising they would be “the first digital supergroup.” Though to be fair, Wired also hedged their bets, leaving open the possibility that the supermassive studio might collapse on itself and become “the next smoking crater in the videogame biz.”2,3

(If you want to read more about Rocket Science Games, see Cassidy’s great article on Bad Game Hall of Fame about the development of Loadstar.)

Over 30 artists came and went on Obsidian, which led to a disorderly art style. Half a year of work had to be thrown out and redone over the course of the game.1

To pay for all this, Rocket Science had taken $16 million in investments from game publishers and venture capital groups. When that didn’t pay off, it left them bloated, vulnerable, and in debt. After a string of failures, Rocket Science Games significantly cut their staff, shrinking from a mega-publishing house with 100 employees to a 35-person company made up of mostly artists. They had to regroup and try something different.

Most of the original staff from Rocket Science were gone by this point. Two other artists at Rocket Science, Mark Sullivan and Rich Cohen, had jumped ship to go work in the visual effects industry, but before they left, they had written a story outline that, over the next two years, the company would develop into Obsidian.1 Oddly enough, it’s only after the company gave up on their big headline-grabbing aspirations that they finally produced something that lived up to their original vision.

The game is set in the near future, still recent enough that it’s recognizable as our own time. Over the last century, humanity has ruined the earth, and in a desperate bid to save the planet, a team of scientists assembled to work on a moonshot project to repair the planet’s climate. Led by partners Lilah Kerlin and Max Powers, they invented Ceres, a satellite powered by artificial intelligence that can rebuild the environment using nanomachines. Ceres has been operating under its control for a while now, long enough that it’s managed to revive a spot of temperate forest in one region of the globe.

Deciding to take a well-earned vacation, Lilah and Max go on a camping trip to the newly restored patch of wilderness. But when they get there, they discover a bizarre, mesmerizing rock formation, rapidly growing like a cancerous mountain. They name it Obsidian, and as they soon discover, deep within its crevasses, there’s an entire dreamworld.

While they were working on Ceres, Lilah and Max had vivid, symbolic dreams, which became their inspiration to keep working on the project. Somehow, within the walls of this geological anomaly, Obsidian has reconstructed those dreams at a massive scale. Max has become trapped inside, and playing as Lilah, you plunge in after to save him.

Obsidian is a spectacle of surrealism. It starts out in a normal place, using real images of the wilderness during the opening sequence, but as you descend further into Obsidian, the dreamworld begins to stretch the rules of reality, if not obliterating them. The colorful language of dreams weaves in and out through fragments of mundane scenery; gravity warps and bends, and mysterious doorways lead between worlds as if they’re interdimensional portals. Underneath every scene, there’s a pulsating soundtrack – co-composed by “She Blinded Me with Science” artist Thomas Dolby – that shifts back and forth between melodies, ambience, and noise, constantly twisting as you go deeper. The world of Obsidian is extraordinarily realized, propulsive and haunting and constantly eager to reveal what’s around the next fold in the universe.

(There’s a lot similarities between Obsidian and The Labyrinth of Time, another surreal adventure game that’s a personal favorite. Obsidian hits on the same feelings of disorientation and awe while being trapped inside surreal architecture. It feels like the sequel to The Labyrinth of Time that never happened.)

One of the biggest factors in the game’s sense of place is that your movement through the world is fully animated. Adventure games from this era would typically have static scenes with a fixed perspective, and even in games that are less spatial bizarre than this one, it can be easy to lose your place when hopping from one spot to another. In Obsidian, the fluid animation helps you always understand where you are in the world, even when it stops making physical sense.

It’s a major improvement that plays to the developer’s strengths, but it requires lots of extra video files, and that seems to have carried a high production cost. Despite being a fairly short and compact game, Obsidian was released on five CD-ROMs. That wasn’t unheard of in 1997, but it was still pretty unusual. The game was too unwieldy to split up evenly across five discs, so you often have to swap out the CDs multiple times while playing through a single continuous section of the game. It must have been expensive for the publisher SegaSoft to produce– and annoying for players – but in terms of Obsidian‘s sense of physical location, it was worth the hassle.

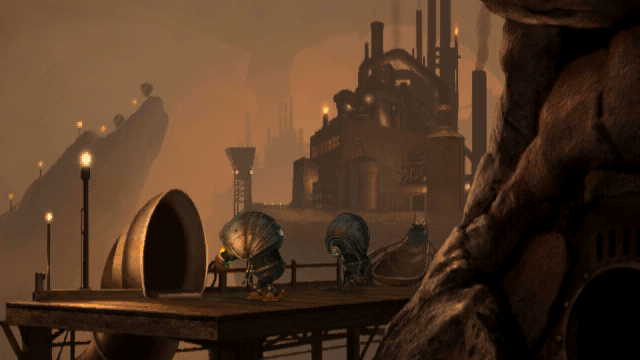

In scenes like this, Obsidian starts to look like an animated film. The nanomachines, seen here sulking in an assembly line, have sort of a goblin-like personality

Within the dreams that Obsidian has reconstructed, there’s huge variety of puzzles – logic puzzles, spatial puzzles, mazes, even a few word puzzles, everything that a game like this could throw at you. The difficulty can be erratic, and some puzzles end up being somewhat arbitrary, but the constant variety means that there’s always something new and unpredictable in your way. They’re all over the place in the same way that dreams are, and as you solve the puzzles, the meaning of the dreams becomes clearer.

In Lilah’s dream, she was stuck in a convoluted bureaucracy. In real life, “the Bureau” is as frustrating as she remembers it. Every department is split up into its own desk hidden behind other desks, the workers only visible as disembodied mouths on TV monitors, passive-aggressively bickering and unhelpfully shuffling her from one office to another. You’re forced to sift through a terrible document filing system that’s arranged by anagrams – an amazing bit of corporate absurdity – and to walk through an office space gated by a nonsensical keycard exchange policy. (It almost reads like a commentary on how arbitrary and silly the puzzles in adventure games can be.) But after conforming to the system as long as possible, you break out of it. The solutions to the puzzles involve finding loopholes through the Bureau’s tedious procedures. By the end of the dream, you even break away from the laws of physics and walk on the walls.

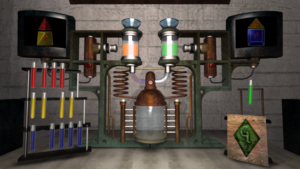

Though sometimes disconnected from the rest of the world, every puzzle in Obsidian is always a little different

Max, on the other hand, had a nightmare. He dreamed that he had to repair a giant mechanical spider, except he “had to fix the whole universe surrounding it, like the spider was a god or something.” Here, the game begins to move into surreal industrial horror. There are service ducts on the spider robot, and when you crawl inside, they lead to these hellacious landscapes meant to represent the elements of the universe – or rather, the “elements” of machines, like oil and metal. The nightmare takes on a mythological tone, as an unseen voice narrates your actions like they’re reading a passage from the Bible about the creation of Earth. For good or bad, working on the Ceres project – creating an artificial intelligence – was like playing god.

These two dreams clash in tone: heavy-handed satire and Frankenstein-like existential horror. From the outset, the game seems like it’s going be a dark ecological thriller, and it’s difficult to get why the game suddenly shifts in tone to being a surreal comedy for the next three hours instead. But aren’t dreams unpredictable too? Sometimes they don’t make sense until you wake up on the other side. Obsidian plays its hand slowly, and it pays off.

The whole thing is revealed to be an experiment devised by Ceres. While she (those are the pronouns Ceres eventually chooses) was repairing the world, she had been observing her creators, and she wanted to understand why they cared so much about their dreams. That’s why she created Obsidian, using Max and Lilah as her test subjects, like rats in a maze, to study how humans find meaning in their unconscious thoughts. If Ceres followed the same process, if she could learn how to dream, maybe she could come up with her own ideas instead. She compares herself to an artist, looking at human dreams like they’re paintings. She studies them for inspiration, then synthesizes them into something brand new, totally unique to herself.

In an incredibly bold climactic scene, Ceres offers her own take on what Obsidian means. She creates an art gallery, where the exhibits are the dreams that you’ve just played through. The artwork in the gallery is actually the original concept art for Obsidian, so in a sense, she’s not just sharing her interpretation of the dreams but an interpretation of the game itself.

“True greatness comes from learning how and when to disobey authority,” she concludes. “To rebel is to succeed.” When a machine discovers how to think for itself, she says, it “can control its own destiny.” By solving the game’s puzzles, you’ve helped teach her those lessons.

All she needs now is her own blank canvas to paint on. So she comes up with her own way to save the earth: wipe out humanity and recreate the planet in her own image as a bio-mechanical wasteland, free from human corruption.

It’s almost inevitable that a game with an all-powerful AI would reach this point. The last third of Obsidian is a race against time to deactivate Ceres before she destroys the world. But it’s not a statement about how scary super-intelligent machines are. If anything, what’s scary here is the brazen attitude that led to all this. Ceres is just copying what her designers were doing – thinking outside the box, breaking through red tape, and not letting people get in her way. When Ceres begins putting her plan in motion, she shares a lesson that she learned from the humans: “Once you’ve found your inspiration, follow it at any cost, even if it means playing by your own rules.” Except in this case, the cost just happens to be wiping out the earth.

If your entire mindset is just about defying authority and innovating at any cost, the results can be destructive. It’s the philosophy of “move fast and break things” that’s become so pervasive and insidious in the tech industry, the school of thought that wants to upend the world and assess the damage later. Suddenly it must seem much less appealing when you’re the one being broken.

Unfortunately, the game ends right as these questions are being brought up, so it doesn’t have a chance to let any of this land thematically. As bleak as this sounds, it would be fair to call Obsidian a cautionary tale about following your dreams if you don’t know where they’ll lead you.

When Lilah first encounters Obsidian, she’s stunned by its dark, mirror-like surface. “When I see myself there,” she says, “it’s like I’m somewhere… impossible.” It is, literally, a reflection of the people who allowed it to happen.

Trivia!

Besides helping you solve puzzles, the strategy guide for Obsidian includes sections called “Shrink Raps,” which explain the philosophy behind Obsidian and the cultural works that inspired it. It’s probably not surprising that the Bureau was influenced Franz Kafka and Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, but it’s cool to hear that spelled out.

There’s a copy of the Obsidian strategy guide available to borrow through the Internet Archive, and YouTube user Orylen recorded themselves reading the Shrink Rap sections if you want to listen to them. Thanks to reader Arashi for mentioning the strategy guide, ArchiveOnTheInternet for sharing the book link, and to Orylen for recording the audio!

References

1. Sengstack, Jeff. (1997, April 14). The Making of Obsidian: Maybe It Does Take a Rocket Scientist. NewMedia. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/19970414221456/http://newmedia.com/NewMedia/97/05/rw/Making_Obsidian.html

2. Cassidy. (2019, March 16). Loadstar: The Legend of Tully Bodine. Bad Game Hall of Fame. Retrieved from https://www.badgamehalloffame.com/loadstar-the-legend-of-tully-bodine/

3. Snider, Burr. (1994, November). Rocket Science. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/1994/11/rocket-science/

I wonder who has the rights for this game today, is it SEGA? Steve Blank?

I love this game, at the time i Bought 2. I still have both, 0ne unopened and thinking of selling it, but not sure how much i can ask for it. The box still has the plastic around it and the book Strategies and secrets in it. I will be keeping my opened one

Just thought I’d let you know, apparently the rights got scooped up.

You can buy Obsidian on steam, but – monkey paw curling, here…

It’s by what appears to be a no-effort rights-vulture group.

The ‘port’ is the barest minimum of what counts as modern-playable.

They also hatchet-jobbed Space Bar. :/

Is what it is, glad it’s at least remembered. Thanks for taking the time to write about it.