The Labyrinth of Time

The bizarre and the mundane shine inseparably in The Labyrinth of Time, an adventure game by Terra Nova Development. Mainly the design of artist Bradley W. Schenck, the game throws mythology, retrofuturism, and art history together into an odd concoction that, rather than come out as a disparate mess, heightens the ordinary and grounds the imaginative. The titular labyrinth is a setting of enormous creativity bound into maze form.

The Labyrinth of Time opens by, literally and figuratively, tearing apart the world’s normalcy. At the end of a dreary, colorless work day, your subway train home falls out of reality. King Minos, the mythical ruler from Greek mythology, is building a time-spanning, pan-dimensional maze from which he plans to enslave the world; his servant, Daedalus, brought you in during its construction. With little time left before Minos consumes all of history, only an outsider such as yourself, with only a quarter in your pocket, can destroy the labyrinth. That’s a tall order, but to quote the game, “but it’s neither dull nor grey.”

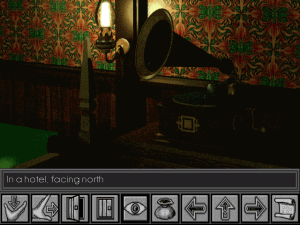

A setting that crosses all of space and time implies some variety, but The Labyrinth of Time‘s chaotic patchwork world goes above and beyond those expectations. The game melds several centuries of history with fantastical scenes into a colorful, violent pastiche. To trace one example, the elevators in an old-fashioned hotel lead to a 1930s office building. The adjacent lounge has been replaced with a crystal mountain cliff, where the mountain tunnels hold a strange portal. The portal, naturally, leads to an old Western settlement that holds King Arthur’s sword behind a buried Cretan bridge.

Needless to say, it’s an overload. This a beautiful and visually complex game, certainly among the most artistically inspired I have ever played. The environments certainly look like the product of 1990s computer graphics, but the blurring between realistic places and total imagination seems novel. Every scene benefits from that boldness. A prominent Medieval castle midway into the game impressively teeters the line between believability (archways and stonework) and unreality (bizarre lighting and prominent magenta colors), but even a broom closet feels more outlandish than expected.

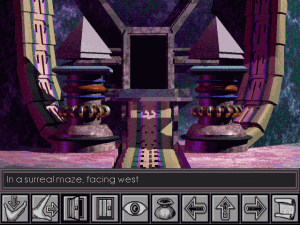

That sort of cartological madness can be disorienting, which both serves and hurts The Labyrinth of Time‘s main conceit. The labyrinth is composed entirely of mazes – some smaller ones inside a larger one – and their surreal disconnectedness holds much of the game’s appeal. That also makes navigation extremely difficult, as the frequent lack of cohesion between areas destroys your sense of direction. An in-game map luckily provides some guidance, but anyone who doesn’t enjoy mazes should steer clear.

Within those mazes, a few puzzles need to be solved, and the game doesn’t seem particularly interested here. Usually, you need to find a key (or key equivalent) and bring it to a door somewhere within the labyrinth; at one point, a sliding 15 puzzle also stands in your way. Mixing items from different time periods is fun, but the focus clearly lies in exploring the mazes, not what you do within them. Sadly, The Labyrinth of Time betrays that ideal at least twice, either by tricking you or disguising puzzles in a way that secretly, irreversibly prevents you from progressing at a later point. This is absolutely heinous but can at least be averted by knowing about them ahead of time (as the game’s re-release warns in the manual).

I might seem too forgiving there, but when The Labyrinth of Time‘s mishmash world works, the joy of the setting outweighs those problems.

All of the labyrinth’s locales loosely connect to the story of an archaeologist attempting to find the tomb of an ancient Mayan sorcerer-king; that offers just enough tissue to build off of the game’s underlying balance of weightiness and silliness. The Labyrinth of Time moves lightly with a Pratchett-y sense of playfulness. It slides across artistic traditions with ease, along the way acknowledging pop culture including the Marx Brothers, The Wizard of Oz, Arthur C. Clarke, and, prominently, The Maltese Falcon. Yet between the silliness, the labyrinth feels meditative, lonely, and enchanting, like wandering through an autumnal garden. Like so much of its style, the game operates on the line between foolery and peace with impressive confidence. The soundtrack follows suit tonally, jumping between swelling orchestras, experimental percussion, and moody piano pieces while always somehow matching the scene.

Despite navigational consistency and sense of place discouraging design like hiding a hedge maze in a 1950s diner bathroom, the labyrinth’s indiscriminatory fusion of everything from ancient Greek architecture to futurism just works. Of particular note is the Surreal Maze, a section of non sequitur surrealist art designed to inspire awe and confusion. The in-game map refuses to display the Surreal Maze, but on paper, it resembles a sphere. That’s just wonderful, and it plays to the same thread of mixed absurdity and wonder.

Some of that awe does wear off after enough backtracking, especially when you have to repeat the same path three times in a row to reach the end-game. Then everything kicks back into gear when you reach that ending, in which you fight a holograph Minotaur in the center of the labyrinth by painting over mirrors. From start to end, The Labyrinth of Time twists normal stories and locations through its irreverent, surreal perspective. Maybe it’s random, but it fits together. A journey through this twisted labyrinth is a deep pleasure, not for what you do along the way but how and where it happens.

Trivia!

The end of The Labyrinth of Time teases a sequel, The Labyrinth II: Lost in the Land of Dreams, that was never produced. The current rights holders, Wyrmkeep Entertainment, have intermittently expressed interest in a sequel, but since Bradley W. Schenck has left game development for his own projects, it seems unlikely to be made.

Video

(This post was substantially revised on February 15, 2016.)