Spaceship Warlock

You are stranded on the planet Stambul. To escape, you have to order tickets for a space flight over a public videophone. You’re meant to dial the operator and ask for the spaceport, but you can also prank-call the emergency line or find the number for the local bar. Then you can visit the bar, order your choice of alcoholic drink, and get thrown out onto the street. Open as those options seem, they’re only facsimiles of freedom: unless you incite the police to kill you, you’re inevitably going to the spaceport. So why not have a little fun and insult your cab driver along the way?

You can’t write the history of the adventure game or the interactive movie without mentioning the operatic sci-fi thriller Spaceship Warlock. As one of the first ever games on CD-ROM, it had the privilege to define what a modern cinematic game would look and play like. Without a roadmap of genre conventions, the game crafts a bizarre template that is somehow roller-coaster-esque in its linearity while still open-ended. Spaceship Warlock barely, barely pulls it off. Not everything gels – especially not the combat scenes – but what works stands out as a high-wire act of guided interactivity.

Spaceship Warlock takes place in “a time long past the conquest of space,” when humanity has surrendered Earth to the robotic Kroll Imperium. Only the ravenous pirates of the titular dreadnought, the Warlock, dare challenge the alien powers. Your nameless but very masculine hero crosses paths with the Warlock after its crew ransacks the prized luxury liner Belshazzar. Rather than kill a strapping young male human such as yourself, the Warlock’s notorious Captain Hammer offers you a job on the ship as part of his end-game of defeating the Kroll and winning back Earth.

The plot and style come straight from pulp sci-fi, with a campiness comparable to The Fifth Element or the 1980 Flash Gordon movie. There’s ray guns, big phallic rockets, and a monotone Robby the Robot imitator. Spaceship Warlock feels ethereal and nostalgic for channeling that aesthetic, particularly in its music. The stock settings look the part, and its worth noting that no other games at the time matched Spaceship Warlock‘s visual clarity. But the reliance on stereotypes also ties the game to some tired and overplayed genre tropes. The biggest such waste is a mandatory romantic subplot with the zero-dimensional “stellar beauty” Stella Starbird, who disappears for the majority of the game and shows up in the last 30 seconds for a cringeworthy reward kiss. Stella seems included as part of a checklist, but for the most part, the game’s adherence to sci-fi formula grounds it and allows its unique rhythms to stand out in comparison.

Although it shares a general structure with later adventure games like Myst, Spaceship Warlock is more rapid and directed. Those other games typically plop you in a non-linear world and let you discover puzzles and challenges at your own gradual speed. Spaceship Warlock won’t have any of that. This is a propulsive game, constantly moving from setpiece to setpiece over the course of its hour-and-a-half movie-length running time. Most areas can only be visited once before a cutscene blows them up or launches you somewhere else. Instead of solving puzzles, you punch aliens in the face. And despite all this, the game finds room to take it easy and let you explore.

To better explain Spaceship Warlock‘s weird pacing, let’s walk through a typical scene from about midway into the game.

After getting out the brig of the Warlock, Captain Hammer orders you to check on a reactor in the Engineering deck of the ship. Fire and radiation have engulfed most of Engineering, leaving you to find any workable path through the makeshift obstacle course. Once you reach the reactor (with the help of a fire extinguisher), ne’er-do-well shipmate Raskull eggs you into a fight to the death. You clock Raskull. Captain Hammer calls you to his meeting room and, impressed with your performance so far, assigns you a room in the crew quarters so you can take a nap. A lot happens in about ten minutes, much of it being told where to go and then going there posthaste. With the search for a fire extinguisher coming closest of any of that to a puzzle, the ride from start to finish is exceptionally streamlined.

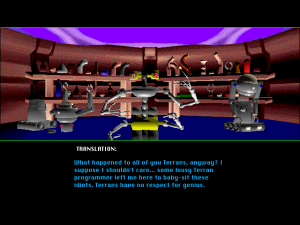

The game distinguishes itself in how you get to those destinations. The Warlock is a wide open environment full of corridors, characters, and interactive scenery, but there’s little incentive to explore given the game’s tight focus. To stimulate that desire, each area along the way (even the hallways to the elevators) uses the same open-ended structure in miniature. The Engineering deck, for example, has a maze-like layout with many routes to the other side. Apart from the entrance and the reactor, you can find maybe six other unique points of interest, including coolant chambers and a dejected repair robot that carries a decent conversation. You can fool around with some gadgets or characters in these side attractions, but you won’t find any new quests or clues. They’re just elaborate window dressing on the road to the next cutscene.

Essentially, for each section of the game, you navigate your own way through a detailed mini-world where all paths and diversions ultimately converge on your next objective, triggering a moment of action that begets a new area. Wander, rush, repeat. If the game itself is a roller coaster, then the bulk of its gameplay is the expensive, thematically decorated queue you wait in before you board the ride.

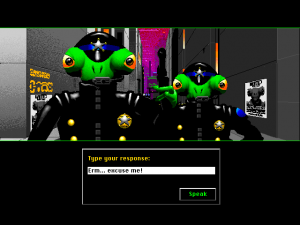

Putting details and interactivity on the margins could cheapen their value, and that almost happens here. Consider a game like Lunicus that offloads a substantial portion of its story to the optional background: unless you took the time to explore every nook multiple times throughout the game – an exhausting proposition – you missed out on most of the characterization and plot. Spaceship Warlock‘s side content avoids such a pitfall by enhancing your settings rather than burying the important parts. If you nap in your quarters instead of going to your objective, you’re treated to a surreal dream sequence, and Captain Hammer yells at you for slacking. If you pass by the mess hall on your way out, a few uncouth crew members will bully you about the food and might kill you if your words upset them. These bits reward curiosity and suggest a larger world beyond the immediate story.

Though these are fun diversions, they don’t fully loosen the game up. In the face of Spaceship Warlock‘s constant urgency, there’s scant reason to seek them out. You might burn through the whole game fairly quickly and wonder why it felt empty. That stings less since you’re missing flavor rather than meaningful chunks of content, but it stings regardless.

Those types of interactions could have gained visibility by replacing some of the game’s many required combat sequences. Whether firing lasers ship-to-ship or punching enemies one-on-one, combat just does not work. Stuttery animations and unresponsive controls hamper any cinematic whiz-bang that action scenes could have brought to the game. These segments seemingly need to exist to complete the intense sci-fi B-movie experience, but their start-and-stop contrast with the rest of the game is disruptive. Spaceship Warlock is already loaded with dramatically scored cutscenes and perilous scenarios; it doesn’t need janky gun fights to be pressing.

But Spaceship Warlock still nearly works in spite of its erraticness. Sure, it’s all over the place, but those morsels of detail nestled around the game glue its messiness into something appreciable. During one otherwise dull shoot-em-up setpiece, for instance, your teammates will shriek with delight if you find gold treasure hidden throughout a Kroll ship. That doesn’t fix the scene, but it feels much better with those little touches. An hour of point-to-point boilerplate science fiction adventure would probably not be compelling, and those somewhat open interactive elements sustain the game’s appeal for exactly long enough. Right as the Warlock runs out of surprises, when the dialogue-driven scenes seem more intentionally constructed and the game loses focus, it ends. And that’s good. It couldn’t be longer.

(And maybe the 50s paperback aesthetic subconsciously sets lower expectations for storytelling quality and tonal consistency. A little cheese can smooth out the cracks.)

Spaceship Warlock strains to assemble a coherent adventure game from its many disparate sci-fi and cinematic influences. And it does, however briefly, come close to solid. Especially considering how few similar games came before it, even this minor success is miraculous. It’s the wobbly cornerstone of its genre, a foundation from which future interactive movies and adventure games could improve the formula. I wouldn’t recommend playing Spaceship Warlock to help Captain Hammer reclaim Earth, but you might enjoy ordering a spritzer, wandering the streets, and beating up an alien before you get there.

For more about Spaceship Warlock, read The Obscuritory’s interview with co-designer Joe Sparks.

Trivia!

Beyond its fame as one of the first CD-ROM games, Spaceship Warlock also gained notoriety as the subject of an intellectual property law case. The game was the product of a partnership between Reactor Inc.’s Mike Saenz and artist/designer/polymath Joe Sparks; Saenz and Sparks had a noteworthy, protracted legal dispute over whether Sparks co-owned the Spaceship Warlock copyright with Reactor. Because of this, the game will likely not be re-released.

UPDATE: In a comment on Game Revolution, Joe Sparks clarified that he owns the rights to Spaceship Warlock. He has been unable to re-release the game for compatibility reasons.

Cool write-up!

I’m still waiting for someone to cover Sparks’s game Total Distortion in detail. There’s more to it than simply having a catchy Game Over song.

I actually did release Warlock again in 1995 through EA distribution, and then again later (1997?) through an aftermarket “bargain-bin” publisher (can’t even remember who we did the deal with). Also, there are some online game re-publishers who have been serving up Warlock over the web (along with many other old games) without my permission for years! 😮 ~Joe Sparks

ScummVM has recently brought in support for Director-based games, and it supports both Mac and Windows versions, regardless of what platform you’re running it on. I tested my Mac copy of Spaceship Warlock, and it works without speed issues.