SoulTrap

In several ways, SoulTrap is a nightmare.

For Malcolm, it’s a literal nightmare. He’s become trapped inside his own mind by his deepest fears, and apparently, he’s scared of everything. He’s afraid of death. He’s afraid of clowns. He’s afraid of fast-paced life in the big city. He’s afraid of robot sharks… which I guess is fair, I’ll give him that one.

And so he must conquer them and escape. His fears have manifested as a dreamworld, so surreal that it borders on abstract.

When SoulTrap came out in 1996, 3D graphics had been around in games for a while, but game designers were still figuring out the vocabulary. 3D games from this period, like H.E.D.Z. or the first attempt at a 3D Prince of Persia game, can have an unhinged quality to them as they experiment with large geometric forms and unconventional, unintuitive level structures. Even by that standard, SoulTrap is alarmingly rudimentary.

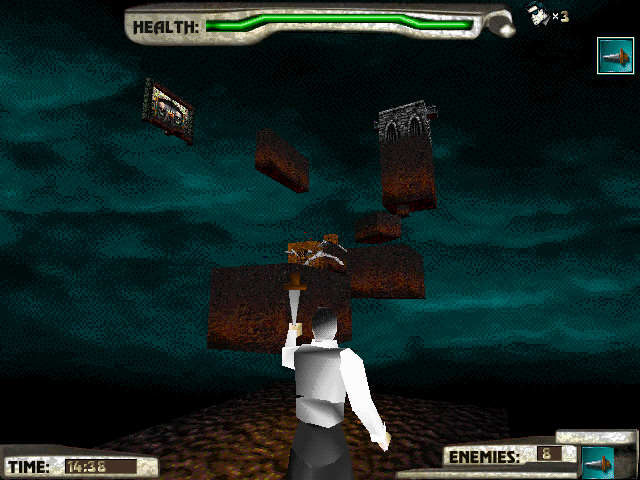

Malcolm’s nightmares are made out of floating blocks, which vaguely reference the theme of the level. Take the second stage, the Gothic dreamworld. It slightly resembles an evil castle, but it’s more like an abstract interpretation of an evil castle, made out of rectangular stone platforms looming over a pit. It reminded me of Bowser in the Dark World from Super Mario 64, another abstract 3D game level from the same year, but cruder and less cohesive.

The dreamscapes in SoulTrap are far from the actual types of places they’re imitating. They’re defined as much by floating platforms as they are by the gulfs of empty space that come between them. The textures in FreekPark that look like canopies and boardwalks are just barely enough to suggest that the stage is a carnival, not just a bunch of islands hovering thousands of feet above a mountain range. It is like a dream – in the way that you might have a dream that takes place in a cave, and you instinctively know that the cave is actually supposed to be your high school.

Disconnected from reality, the game does wild things with its arbitrary, boxy levels that a more principled or thoughtfully designed game would balk at. Giant platforms will spin around, not with any intent, but just because, well, it’s a 3D game, and they can do that now. Portions of the world appear and disappear as needed, and they’re linked together across long distances by fast-moving platforms, gondolas, and hot air balloons that whisk you off into the unknown. The vertical scale of SoulTrap is absurd and terrifying, especially in the relentless level Vertigo, where you climb up chunks of skyscrapers suspended in the air and one misstep sends you all the way to the bottom.

Keeping with the dreamlike nature of the game, the levels in SoulTrap meander wherever it strikes them at the moment. They climb up, then fall down, then go up again and fly off in another direction, like doodling a line, operating almost at an unconscious level. Because of the way the game renders, you can only see about 100 feet ahead of you. That’s perfect, because the game feels like it was designed 100 feet at a time.

To be clear, these levels are not well-made – barely coherent in their direction at times – but by accident, they’re a good representation of the flightiness and irrationality of nightmares.

But the game truly becomes a nightmare because you have to play through these levels on a hoverboard. Malcolm rides through his mind on a Jetboard, a device that glides through the air but has trouble handling once it leaves the ground and easily slips off the edge. Sometimes the worlds of SoulTrap are built around the Jetboard’s physics, with shallow leaps and roomy floors, but there’s always sections where you need to jump (and fall) accurately across small platforms. The Jetboard just can’t stick the landing neatly. Even in his dreams, Malcolm couldn’t imagine a slightly better hoverboard.

There’s a myriad of issues at play: poor traction, wide variation in jump height, difficulty judging how far you are from the ground. The Jetboard can be stopped abruptly in mid-air at the press of a button, but that feels like the game surrendering to its poor controls and patching over the problems without actually addressing them. Platforming in 3D took some time for game designers to work out (see Alpha Waves, an abstract 3D platformer from six years earlier that, like SoulTrap, can switch between first- and third-person perspectives in the hope that one is less awkward), and the Jetboard turned out to be a crummy way to do it.

The biggest letdown in this regard is Breakfast of Champions, a stage made out of larger-than-life breakfast foods inside an ethereal Waffle House. I love this idea – is Malcolm scared of a balanced breakfast?! – but it hits all the same problems with tiny, staggered platforms. If anything, it’s too abstract for its own good.

And then we come to the egg.

After braving the gauntlet of deadly milk cartons and spelling the names of different breakfast items, Malcolm comes face-to-face with a colossal Rube Goldberg machine and a human-sized egg. Calling it a machine might be inaccurate: it’s a collage of rapidly moving rectangles that barely looks like anything. When you start the machine (by shooting it), the egg rolls down a conveyor belt, and you have to push the egg at the right time so it falls into a vice that will break it open. I spent 15 minutes trying to work this goddamn egg-cracking contraption, and the egg kept making its way back to the start, unharmed, waiting, silently taunting me for my speggtacular failure.

This terrible, surrealistic torture device comes out of nowhere. It’s unlike any other obstacle in SoulTrap. What it has in common with the rest of the game is its primitive surrealism that could only have been dreamed up, how else, in a nightmare.

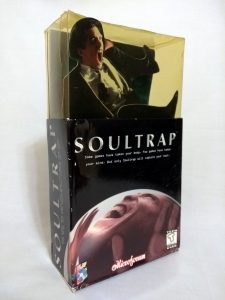

Look at this box!

I didn’t know how to fit this into the article, but I couldn’t talk about SoulTrap and not mention the packaging for this game. While most computer games were shipped in boxes with artwork on the front, SoulTrap came in a box that looked like this:

Unfortunately, my copy is damaged and discolored, but as you can see, that’s a diorama of Malcolm screaming for his life, trapped on top in a plastic prison. I love the creativity put into this packaging and how it embodies the bizarre, simplistic 3D nightmare world of SoulTrap. It certainly would have stood out on store shelves. I think it’s the reason I learned about this game in the first place!

A note on compatibility

SoulTrap has trouble running on most Windows 98 emulators. I recommend playing it using PCem, which handles 3D graphics in Windows 98 the best out of any program. See the Resources guide for further instructions on configuring PCem.