Lighthouse: The Dark Being

The company Sierra On-Line was once one of the biggest names in the adventure game genre. Eventually, their style of unforgiving third-person adventure stories fell out of favor, replaced by a new style of contemplative, first-person adventure games, popularized in 1994 by Myst. With the popularity of the genre shifting, they took one shot at making an adventure game in this new Myst-inspired style.

And it was, blatantly, inspired by Myst. Jon Bock, designer and art director of Lighthouse: The Dark Being, told me via email how the project got started. “[Sierra president] Ken Williams called me into his office one day, pulled out a copy of Myst and said; ‘Can you do this?'” Bock recalled. “I said yes, and the game went into development.”

On its surface, Lighthouse reads like it was designed by a committee trying to nail down what made Myst successful. You visit a bizarre uncharted world where you solve complicated puzzles in open-ended locales with complex mythology and lots of journals to read. In spite of that copycat-ery, Lighthouse manages to leave its own mark on the genre — partially because it manages the awkward feat of carrying Sierra’s frustrating, player-hostile house style over to this new style of adventure game, but also because of the world it creates, filled with risk, conflict, and a huge thematic swing for the fences that few Myst clones attempted.

Lighthouse tells a Stephen King-y story of otherworldly secrets. You live alone in the Pacific Northwest, attempting to stave off writer’s block. One particularly stormy evening, your neighbor, the scientist Dr. Jeremiah Krick, frantically calls you to his lighthouse home to assist in a life-or-death matter. As you discover, through his experiments, Dr. Krick has transformed the lighthouse into the receiver for a trans-dimensional portal. The creature living on the other end, the eponymous “Dark Being,” has taken Krick and his daughter Amanda away to his volcano lair for unknown, nefarious purposes. Out of a sense of obligation, or maybe with little left to lose, you dive into this new world with no way home.

But being that this is a Sierra adventure game, Lighthouse can’t help but import the sorts of frustrating inventory puzzles and dead ends that the company became known for in their games like King’s Quest. Myst is famous for its sometimes unparsable machine and logic puzzles; Lighthouse does that too; some sections are lifted almost directly from Myst, like a deeply uninteresting underground maze puzzle that seems inspired by a similar puzzle from Myst. But it also comes with the addition of Sierra-y sections where you have to grab every item not nailed down on the shelves. Lighthouse is the type of game where you have to learn how to pilot an alien submarine with dozens of unlabeled knobs and levers, but also a game where if you forgot to pick up an umbrella from your house at the start, you can’t solve a puzzle in the volcano lair at the very end.

Somehow, Lighthouse captures the pain points of both styles of adventure game — though at least operating the half-functional machines that you encounter throughout the world can be fun if you’re following along with a walkthrough. Sierra would later release patches that addressed some of the game’s difficulty spikes and added a much-needed hint system.

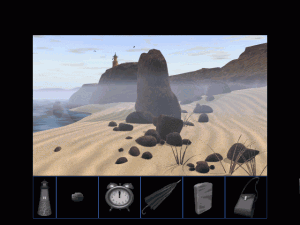

So what makes Lighthouse interesting and worth playing? It’s all about its setting, a world still crawling its way out from an ancient conflict between technology and nature. Sierra resisted the temptation to follow Myst‘s template of a sparse story revealed in secondhand glimmers. Things certainly start that way, with scattered journals and implied environmental storytelling at Dr. Krick’s lighthouse, but the world you stumble into has a clearer ongoing struggle that you’re seeing only a slice of.

In Lighthouse‘s second dimension, a cabal of priests have labored away to restore the planet from its self-inflicted environmental apocalypse. Their order died with their work still in progress, and in the process of defeating the Dark Being, you have a chance to advance their cause. In contrast to the Dark Being’s rusted, smoky machinery, they constructed a sinuous, beige world from more conscientious technology. Among the most memorable characters there are Liryl, an ailing temple guardian whose dehumanizing spiral into loneliness reflects her decaying world; and the Birdman, a mechanical bipedal bird corrupted by the Dark Being who terrorizes the innocent and overthrew his inventor.

Though you only see a piece of this continuing conflict, it dominates the game. There’s a strong, explicit narrative guided by visual language, elements that defy the stereotype of other fix-this-crazy-machine games. And unlike games with more obvious hooks for puzzles or navigation, this world doesn’t exist to serve the player.

Unlike many exploratory adventure games that allow you to retrace your steps if you get lost, Lighthouse forces you to recover from your mistakes. Though the game can be completed from start to finish in a linear, well-planned path, your chances of plotting such a straight course without the aid of a walkthrough are slim. Dozens of possible hazards can sidetrack you if you head in the wrong direction. Early in the game, for example, you can prematurely enter a portal to the other world, potentially leaving you without key items or forcing you to improvise until you can find your way home. Or if you can’t fix the submarine in Martin’s Roost, you can use a flying machine instead that takes you to different destinations. Discovering this interconnectedness is one of Lighthouse‘s strongest hooks. Should you have an important puzzle piece destroyed by the dastardly Birdman, the world wants you to find your own way to catch up.

It is often artfully executed, even little flourishes, like using the empty space around the border of the screen for picture-in-picture closeups of items or environmental details. Sometimes, the environmental ingenuity, narrative tension, and contraptions sync up together, like in a segment where you discover a path back to your home dimension, only to realize your resources and finite and there’s only so many times you can travel back. Too frequently, though, those bits stand separately, despite their similar themes of discovering how to function in another world. The complex puzzles where you pull levers usually don’t interact with the character-driven scenes. When the best bits come together – bizarre devices, emotional engagement, and Birdman – it really works, but not often enough.

There’s an admirable risk behind what Sierra attempted here, bringing these two subgenres together. Games like Myst threaten to get you lost or stranded in a bizarre world you don’t fully understand. Lighthouse actually has the gall to carry through with it.

Developer commentary

Designer Jon Bock was kind enough to share some of his insight into the game’s development, as well as inspiration for the art design for this “science fiction folk tale.” Turns out Birdman has a deeper history than you’d expect! Here’s his comments, verbatim:

In many ways Lighthouse was the height of my career with Sierra. My long term goal at Sierra was to become a game designer. With Lighthouse I had the opportunity to both design and creative direct the project. After the success of Myst, the company wanted to do a fully 3D rendered adventure game. At the time I was working as 3D art director, responsible for the selection of modeling and animation tools, and for managing 3D resources. As art director on Island of Doctor Brain and Outpost, I already had a few years of design experience, and was pushing for a full time design position. Ken Williams called me into his office one day, pulled out a copy of Myst and said; “Can you do this?” I said yes, and the game went into development.

When I began writing the story, I wanted to combine aspects of science fiction, fantasy, and folk stories. I referred to the game as a “Science Fiction Folk Tale”. Some of the settings were inspired by role playing designs I had created years before. The tower the player first encounters when entering the parallel universe was originally a pencil and paper design for a D&D adventure called “The Roost”. The tower was built by a tinkering magician who created mechanical birds and then a birdman, which ultimately killed his creator. Kind of a mini Frankenstein tale.

The world the player arrives in is inspired by the machine age, from the drawings of Leonardo De Vinci, the stories of HG Wells, and the integration of machines and natural forms, resulting in a steam punk-like universe. The “Dark Being” is a trickster character, a combination of traditional trickster characters like coyote with the Grinch who stole Christmas. His use of technology is destructive, the antithesis of the overall philosophy of integrated technology and nature that is the foundation of the parallel world.

It was important to me to have 3D animated characters in the game to bring the world to life. Our models were built and animated on SGI machines using Alias, and our motions were created at Biovision. The landscapes and architectural settings were created using both Autodesk 3D Studio and Alias. To my knowledge it is one of the first adventure games with fully rendered and motion captured characters.

Thanks a bunch to Mr. Bock for sending this along!

Video

This article was substantially revised on January 23, 2022.

Good to see another review up. Love reading them!

Oh hey its that game that made me sleep with the lights on for 2 years when I was 6 ha ha ha ;-;

I didn’t quite understand the story behind the Dark Being. What are his motives? Kidnapping the child just to press 2 buttons?! He could just made a mechanism for that. Lyril mentions that the Dark Being mysteriously appeared in Volcano. Does the game give more information?

I can’t remember for sure, but I don’t think the game explicitly explains much more about where the Dark Being came from apart from Liryl’s comment about how he comes “with the ways of the past.” The thing that confuses me is that he’s almost feral, but he also reverse-engineered a machine that can travel between dimensions.

My interpretation is that he’s almost like an allegorical force of ruin. The old world was destroyed by an advanced civilization that let their power grow unchecked, and the Dark Being is like the ultimate version of that selfish exploitation. He’s intelligent, but his only motivation seems to be harming anything around him. Maybe he’s one of the last descendants/survivors of the people who ruined the planet.

The GOG release comes with the “Lighthouse Player’s Handbook” written by Jon Bock which mentions that the game is branching and that it’s actually impossible to get completely stuck. It’s only 14 pages so it could have originally been a pack-in. I can’t find any documentation of how many paths there actually are or the endings (the handbook mentions 16 total), so how much the game changes or how many endings are actually early “failure” ones isn’t clear. I’m in the process of playing it now, and it does seem to be fairly ambitious especially for a Sierra game.

When I was a kid I somehow got it into my head that this game was based on Stephen King’s Storm of the Century. I even got my dad to buy me the book and of course it turned out to be completely unrelated, but it at least got me into reading more Stephen King.