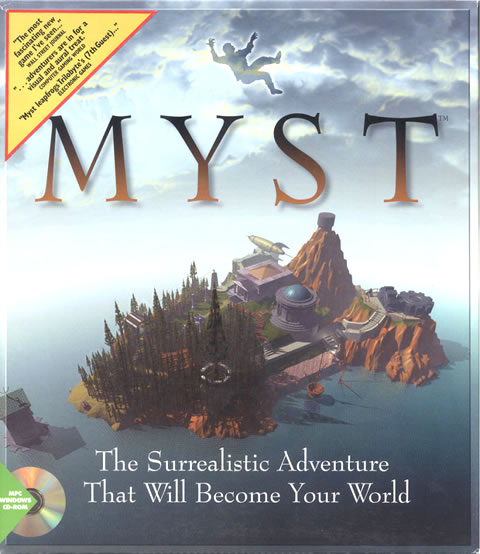

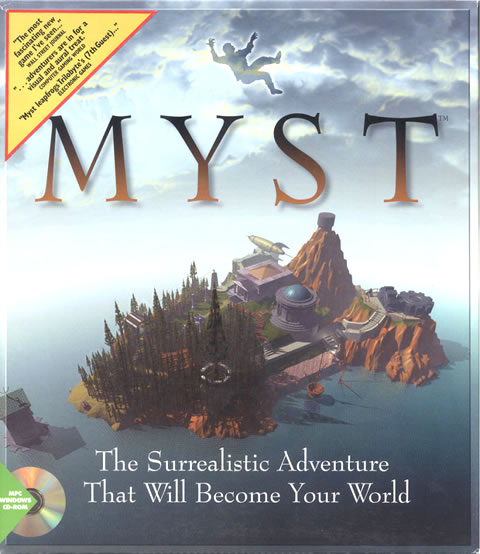

Congratulations, Myst, go buy some lottery tickets!

Given that it has become something of a punchline for boring and uneventful games, it can be difficult to acknowledge the impact Myst had on gaming. Myst wasn’t the first CD-ROM game, nor the first point-and-click adventure game (even from that year – Return to Zork and The Journeyman Project beat it to the punch). It was the most accomplished, though, and the most technically stable given all the music and video flying around, and it hit at exactly the right moment.

Rolling Stone declared Myst to be “a breakthrough” and “as close to virtual reality as we’ve come.” The Village Voice went as far as calling it “one of those works that irrevocably changes the parameters of an artform, multimedia’s equivalent of Don Quixote or Sgt. Pepper’s.”

Myst got people thinking in terms of places instead of stages. There’s a popular refrain that Myst led the adventure game genre astray, kicking off a deluge of abstract, unengaging puzzle box games that removed characters from a format dependent on interaction and dialogue. But Myst also proved the merits of open-ended, environmental storytelling interlocked. It was okay to make an experience, even if people considered it more of a slide show than a game.

Best of all, you could play it in your home computer. Myst sold millions and drove interest in the CD-ROM format to a degree no other game had accomplished.

Myst gently but unquestionable curved the direction of future video games. It may not be a perfect adventure game, but from the perspective of this blog, it may be the most important.