Millennium Auction

Eric Roffman had a Ph.D in mathematical physics, and he wanted to make games. After working on an interactive LaserDisc poker title, Roffman looked for a way to combine his interests in science, games, computer graphics, and film. So in 1990, he started Personal Media Interactive, a company that would develop “projects that looked at the future, or combined gaming with interesting ideas, including a number of games designed to be both intelligent and entertainment.”1

They would make “intellitainment,” as they awkwardly dubbed it, multimedia games for adults.

Intellitainment began and ended with their only title, Millennium Auction. As the title suggests, it’s an auction game, a genre Millennium Auction basically made up. Auctions have an unpredictable, suspenseful rhythm, so Roffman planned a game around them as a way to experiment with a variable, randomized narrative in a speculative setting.1

The game certainly delivers way more intrigue than I expected from a virtual auction with nothing at stake. Chance plays a major part in that, though, and it raises questions about the role of randomness as a narrative tool.

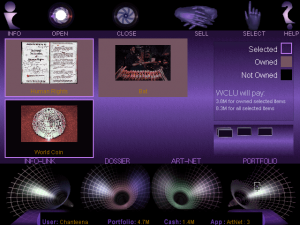

Millennium Auction‘s future is the year 2011 – as envisioned in the early 90s, exaggerating those years’ trends in international politics and communications. The newly formed World Body government has total control of the planet. Everything filters through InfoLink, a virtual reality network that regulates identity and finance. Today, the World Body Auction House is hosting a once-in-a-lifetime sale of the world’s most treasured artwork and historical objects. For once, there’s no mystery to solve. The action never leaves the auction house. You and the other members of high society are here to bid.

So why would you participate in an imaginary auction? You can’t price a non-existent item like the “Astrobot prototype” or real, unsellable artifacts like the bullet that killed JFK, and of course, you’re not motivated by really owning them.

Millennium Auction isn’t about the individual items, despite their elaborate backstories. The game wants you to sell them for a profit, and in an auction house full of cutthroat buyers, that’s not easy. Everyone knows the market value of the twelve items on the auction block, so they rarely go for below asking price.

Instead of looking for a steal, you want to bid strategically. A few collectors will pay premium for a set of three or four pieces, so getting a group with a high total markup is a safe plan. Assuming your competitors don’t get the same idea (they could buy a portion of the same lot you’re pursuing), your purchases can still gain or lose value. Prices fluctuate naturally over time, but they also depend on external circumstances. Throughout the auction house – especially in the office of Zeke the friendly, resourceful janitor – televisions, radios, and newspapers clue you into randomly chosen world events and expert appraisals that might affect your portfolio.

Consider the case of the final ball pitched at the last Major League Baseball game. (The MLB shut down in this timeline.) A newspaper reference to historian confirmed that this ball was the real thing, so I figured it would rise in value and a slightly higher bid would be okay. Shortly after the auction, though, a Japanese baseball league announced their first expansion into America, immediately ruining the novelty of the last American baseball. I didn’t know something like that could happen! I had to eat the cost, like when Nicolas Cage had to forfeit that stolen dinosaur skull. If only I’d sold it sooner. Think of your purchases like investments, and expect some to be a little more volatile.

As the story behind that baseball suggests, these news briefs and the item descriptions hint at a bigger story simmering underneath Millennium Auction. True to PMI’s mission, the game sneaks in a portrait of a digital, globalized future, one that paved over its old institutions after a nationalist trade war nearly engulfed the planet.

Apart from getting the date wrong, this futurism isn’t too unreasonable. It’s also extremely silly. InfoLink’s presentation falls for the cheesiest 90s virtual reality tropes – blobby graphics, a convoluted drag-and-drop interface with “portals,” tunnels of light to switch between screens, and a belabored, breathy tutorial voiceover. Yet these are perfectly good reasons to love Millennium Auction, too, and not merely for kitsch. The Cold War ended during Millennium Auction’s development, and the game tries its best to anticipate the fears and possibilities of the coming connected world. It encapsulates the dorkiness of millennium-era yearning, taking earnest interest in where we’re all going and expressing it with goofy wireframe models.

That anxiety stays under the surface, for the most part. Millennium Auction keeps its focus on the auction – and on the dynamic stories within there.

The other bidders have psychological profiles that affect their strategy. InfoLink contains dossiers on each person’s background, thrown together from news clippings. The suggestions about their personalities vary in subtlety: business mogul Rasheed Ahmad seems preoccupied with paternalism and legacy, while artist Tory Swift directly monologues to a reporter about her concern for the environment. The best profiles don’t immediately reveal how their subject might behave. Young business heir Randall Prescott Smith is apparently impatient and isolated, and he runs a disreputable art collecting organization that may have ill intentions. It’s intriguing to picture how that might figure into his auction style.

Honestly, though, there’s no way to tell. You could eavesdrop on every conversation to inform your choices, but when you’re actually bidding, you can’t filter personality from random AI behavior.

The auctions crackle with drama. Every long pause between bids builds pressure. The audience gasps when the price goes too high, and the top bidders seem to be trying to psyche each other out. How much does character determine their actions? Did that tech genius linger on their last bid because they like to keep a low profile, or did the game arbitrarily wait for a second? The same concerns apply when considering what factors might sway item values: does the player risk putting more thought into them than the game does?

Are we projecting our own expectations onto random occurrences, like those pictures of signposts and faucets that look like faces? If we still enjoy the story, maybe the intention doesn’t matter. The signal and the noise don’t have to be separate. People are erratic, and so are world events and sudden bidding wars.

Semi-randomized storytelling like this gets old after a few iterations when you start to notice the Mad Libs-like patterns, but Millennium Auction‘s novelty only carries enough interest for a single playthrough – short enough not to spoil the effect. And during that one time through, you can get caught up in the psychology of aggressive bidding without feeling like you’re overdoing it.

And you should overthink it! Millennium Auction is best enjoyed when taken too seriously. You get a better mental workout if you totally submerge yourself in the setting, goofiness included. It inspires fun strategies: I would purposely drag out an auction I didn’t intend to win just to tempt my opponents into spending too much.

(The game also allows additional human players in place of the AI characters. That could lead to more cutthroat strategy, but it negates the investigatory, character-driven role-playing parts of the game. It also doesn’t have a good way for multiple people to use the InfoLink without taking turns and waiting.)

Millennium Auction doesn’t go as deep into its alternate future premise as it could. Instead, the game tells a story that blurs the line between world-building and random statistics thanks to the power of suggestion. Like tabletop or live-action role playing, but with asset management as the main source of tension. The approach works well for Millennium Auction‘s smaller, non-violent situation, and you could imagine expanding the idea, maybe into a political thriller that explores the dynamics of a speculative world more fully.

Post-mortem

Unsurprisingly, though, that was the end of intellitainment. Millennium Auction was not successful, and the studio disbanded shortly after the game’s release. The story of the game’s troubled production sheds light on the struggles that new developers could encounter in the 90s multimedia landscape, plus some pitfalls unique to this company. It was a miracle that they finished the game at all.

PMI was buoyed by a $2 million investment from Armenian construction magnate Berj Kalaidjian,2 an unusually large budget for a multimedia CD-ROM at the time. Eric Roffman says his game concept attracted interest at trade events from big names including Electronic Arts and Bill Gates,1 but after two years of production, PMI had essentially nothing to show.3 With his mathematical physics background, he had seemingly limited experience managing a project at this scale. Kalaidjian grew restless. As Roffman recalls, “[Kalaidjian] felt the project was taking too long and we had a shake-up.”1

In 1992, the company approached Michelle Blank, an emerging-tech-focused strategist, to serve as vice president of business development and work on marketing.2,3 According to Blank, when she interviewed for the position in April, Millennium Auction was barely in pre-production – and they wanted to launch in October.3

I came in interviewing probably about four months before what was being represented as the planned launch date. […] And so I said, “Oh that’s awesome. You must be in beta.” And Eric goes, “Well, no.” I go, “Oh, okay, you’re not in beta and you think you’re gonna launch in four months from now? Well then, you must have like an alpha version.” And he goes, “Well… not really.” I said “Oh, okay, so you can’t show me a beta version, and you can’t show me an alpha version. […] So do you have a detailed, you know, functional requirements – the product specs, you know, for the game […] to be driving the development?” And… they didn’t have that. […] I had first been approached to do business development, and then I quickly realized that there was no product, at this point, to even begin in any kind of business development because we were still in the early stages of product concept development. […] There were a couple of ideas, and they had hired great, you know, 3D animators and artists and all this kind of stuff, but they weren’t going anywhere because there was no well-defined product.3

Blank further characterized the game up to this point as “at best, a one-page description of this game set in the future […] where people are competing with a unified money system for historical art pieces.”3

Still, Blank was interested. Though she initially declined to join the company,4 Blank recognized the growing market for socially oriented multimedia games “targeted to a different population than your typical hardcore gamer.” She believed the Millennium Auction concept, with its focus on art and social interaction, could capitalize on this.3 She came aboard the next year.

As part of the company’s reorganization, Blank took on a larger creative and project management role in the company.3 She approached it, appropriately, like a business developer. Blank led an effort to rework Roffman’s original concept, which stuck closer to what she labeled “purely esoteric classical art.” In an effort to widen the game’s marketable appeal, the team emphasized the title’s “social multiplayer gaming” aspects, as well as introducing lighter pop culture-related auction items, like Bill Clinton’s saxophone.3 Roffman says humor was always meant to be part of the game,1 but according to Blank, he bristled at the new direction.

Roffman was dissatisfied with the changes to his company and the project. He quit shortly later.3 At some point in this process, PMI was rebranded Eidolon. (Programmer Jim Berrettini suggested the new name to evoke the illusory nature of their game’s characters.4) Despite only receiving special thanks in the final product, Blank became, as Robert McNatt put it in Crain’s New York Business, “the de facto chief executive.”2 She effectively took control of the company to get development back on track. With the new leadership, Roffman’s futurist vision seems to have taken a back seat to actually getting the game done.

Pop culture jokes like this riff on the Nancy Kerrigan attack were meant to appeal to people who didn’t care for art history

“I don’t want you to think that I came in and all of the sudden we had this like, fully fleshed-out functional specifications. No!” Blank said. “We certainly had a framework that didn’t exist before upon which we could now put flesh on.”3

A rowdy, freeform year of development followed. The expanded (but still small) Eidolon team huddled together at a house in the Riverdale neighborhood of the Bronx, “chain smok[ing] and trad[ing] bad jokes.”2 Because of their intimacy, the team could constantly bounce ideas off each other and come up with characters and game ideas organically. The game was developed more-or-less on the fly from there.3

As a testament to their collaborative environment, one person, David Rosenbloom, received shared credit as writer, programming lead, game designer, creative director, project manager, and original music composer. Blank says he was “responsible for managing developers” while she dealt with the big picture business strategy. For the record, she said “[it] was not important to [her] to be credited.”5 But how many Michelle Blanks are out there who never received credit for their work behind the scenes?

On top of all this, Eidolon had always planned to self-publish,1 a steep challenge for such an peculiar game meant for an atypical audience. The company pursued an aggressive retail marketing strategy based on eye-catching, over-the-top box art and highly visible placement on store shelves; Blank recalls seeing copies in a store window on Fifth Avenue in New York.3 To take some of the work off Eidolon’s shoulders,2 Blank courted companies like Broderbund before partnering with Electronic Arts to handle the game’s distribution.3

Eidolon’s designers, artists, and programmers worked closely together to create characters like Chanteena

Somehow, they got the game out by fall 1994. In an interview with Newsday, Eidolon marketing director Lonnie Stein tossed around a Millennium Heist concept for a sequel,4 but it probably didn’t go further than throwing around an idea. “Everybody… it was a project of love,” Blank said, “and it was sad when people realized, you know, there was not funding for the company to move forward.”3

Despite the growing audience for games during the multimedia era, Blank thinks intellitainment may have debuted at the wrong time. “If you actually look at where the point of the market development was, you were really still getting most people who are hardcore gamers or into technology, right?” she said, contrasting that with the popularity of social board games today. “So [the concept] was misaligned with who was buying video games at this time. […] I totally think that there is a market […] beyond the more violent, hardcore video games that I think are really not elevating anyone’s cognitive capabilities or social skills. But we’re talking more than twenty years ago, right? I mean, it was, it was just… there weren’t enough computers with CD-ROM drives sitting in families.”3 It’s true that the game’s especially strange concept may have been out of place in that market at the time, but it doesn’t easily lend itself to a social multiplayer experience, as Blank had tried to pivot towards. It might never have found an audience even in the best circumstances.

Eidolon is the quintessential struggling 90s CD-ROM developer story, and the messy production of Millennium Auction serves as a good lesson about running loose with big ideas. Roffman had the freedom to explore new modes of storytelling and maybe invent a new genre, but the pursuit of those ideas got sidetracked when they ran up against the realities of managing and marketing a big, unconventional project.

Trivia!

Clicking the Credits menu button while holding and quickly releasing the Control key will show a picture of the Eidolon development team in spacesuits while Nuria, your virtual guide in Millennium Auction, sings an extremely creepy version of “Daisy Bell” a la HAL 9000.

Video

References

1. Roffman, E. (2017, April 28). Email interview.

2. McNatt, R. (1994, February 14). Multimedia phantom courts adults. Crain’s New York Business, 10(7), 3.

3. Blank, M. (2017, May 11). Phone interview.

4. Fetherston, D. (1994, April 4). A game for the new millennium creators hope their multimedia software will be a hit with adults. Newsday. C03.

5. Blank, M. (2017, June 30). Email interview.

I’m thrilled to see your detailed write-up of this game. I originally saw it reviewed in a PC game magazine and it took me years to find a copy. I’m the proud owner of the full boxed edition which includes board game style scorecards with little minigolf pencils. This is such an intelligent, wildly creative, artistically bonkers game. Such a rare gem and a wonderful example of the early CDROM era.

Where can I download the game

Amazed anyone else even wanted to memorialize this game. I got it for $10 back in the day in Australia (for perspective, standard price for a game in Australia is $ 100-140) so it was selling very poorly and the discounting reflected that.

However I did end up liking the concept and the game was somewhat playable while the novelty lasted, the “intellitainment” aspect that was nice brain food and the weird abstract art used in the gallery conversations. In general I miss this early era of CD-Rom games and also that first generation CG look back in those days.

These days it would probably find a bigger niche than it did originally. Fantastic how you even managed to find the dev history on this. Quite an interesting one. I definitely wondered how much those early companies were funded for and what it even took for them to get funding vs how how hard it relatively is now… $2 mil seems like a crazy mismatch for the market given how small it was back then too

I think it’s similar to how venture capital is dumping money into tech startups with the hope that at least one investment would pay off in a huge way. $2 million is definitely a lot, but in 1990, computer software probably seemed like an area with a lot of possibility for a breakout success. Though the fact that PMI had to get money from someone in real estate suggests that they couldn’t persuade people more familiar with the industry who might have known it wouldn’t pay off.

I was one of the 3D CG Artists who worked on this Game with my good friend, Yoni Koenig…I also wrote some of the Sci-Fi / Satire and most of the Art History snippets peppered throughout the Game….It was a lot of Fun at first because it was an unexpected mix of artists and programmers with similar interests thrust into a loosely defined “Auction” based concept that was chaotically unformed without any cohesive character development nor storyline….We quickly rifted into a Post-Modernist vision heavily informed by Kurt Vonnegut, Tom Robbins, and William Gibson while seriously constrained by early PC playback limitations….We did our best to overcome those serious technological limitations of the early 1990s by over-compensating with Creativity, Intelligence, and Humor while we could get away with it….About the time that we were finally achieving a viable storyline with characters and while the programmers were experimenting with game play we were suddenly bum-rushed for Release by newly hired Blank….We (Design Team & Programmers) knew we were nowhere close to that stage and the final version obviously suffers from that fateful mismanaged rush to Market….It also accounts for several disputes that eventually resulted with me leaving on very bad terms with (mis) Management….Fortunately, Yoni Koenig and I have remained friends for past three decades while we pursued different career tracks….Yoni continued with a successful career in the Game Design Industry while I continued my Fine Arts Career and taught the past few decades at several prestigious Art Colleges in NYC….FYI: Millennium Auction won two CADDIE Awards from Autodesk 1993 for our CG 3D Designs while this Game also got a half page review in Feb. 1995 issue of “Art in America” ….Probably the first if not only CD-ROM game to get critical review in a prestigious art magazine…..For that reason we are still proud of the artwork and creative writing that we did back then and it has been a pleasant surprise to occasionally meet gamers during the past few decades who know and loved this game despite its obvious technical limitations….Although Not a Financial Success this game has been a Critical Success…..