Grizzly

The readme file for Grizzly, a fighting game with teddy bears, tries its best to explain the strategy for the game, but it can’t.

“I haven’t personally game tested Grizzly enough to say how involved the strategy is in Grizzly, but it does exist nonetheless,” developer Adam Winiecki says. He goes on to claim that some people play the game for eight hours a day, or at least he imagines those people are out there, and if they are, “[they] have strategies which are so complicated they couldn’t really explain them.”

If the creator of Grizzly can’t explain Grizzly, I can’t really either.

It doesn’t quite seem to know what it should be. It’s strangely, uncomfortably intense and dramatic while trying to be silly. The tonal mismatch in the game is severe – in a way that’s compulsively, compellingly wrong.

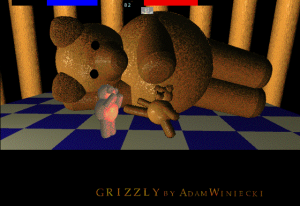

Grizzly version 0.4 makes some feints towards being a parody of fighting games, like a Mortal Kombat-style booming announcer and the stage background with a massive reclining teddy bear sculpture in homage to the Buddha statue from Sagat’s stage in Street Fighter II. But for the most part, it treats teddy bear fights with a bizarre intensity all of its own.

The music stands out over anything else. The single music track in Grizzly is a two-second loop of somebody slamming on drums and a sample of a grizzly bear. It resembles no known human sound. The pounding and growling noises grow more unnerving the longer they go on. It fits perfectly with the incredibly stiff, unballetic movement of the teddy bears, staggering across the stage and pummeling each other.

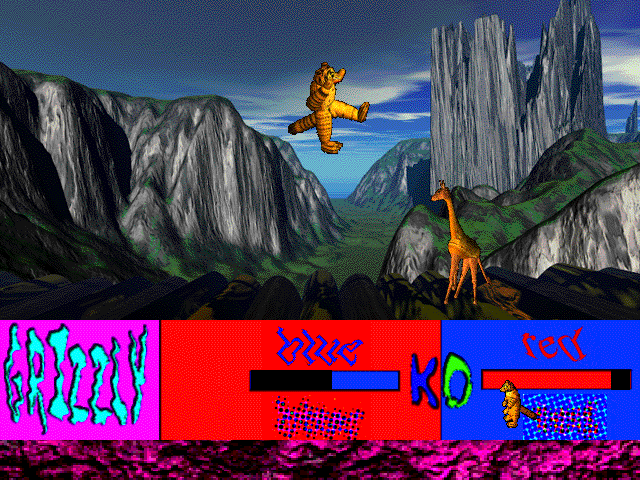

Grizzly is a primal game, almost ritualistic. All the text in the game uses a thin, stretched-out, textured font, as if the words were carved from multi-colored stone or summoned out of a fire, bearing a warning. The teddy bear portraits on loading screen seem to represent some half-realized symbolism for a battle between light and darkness (or, at the very least, the icon for player 2 on the loading screen has black fur and glowing red eyes, which don’t appear in the actual fights). The arena where the bears fight may be meant to resemble a crib, the underside of a kitchen table, or some other household setting, but it looks closer to a forebodingly lit temple. It feels like the bears are fighting for their souls.

You might expect a game about teddy bear fights to be sillier. The game was trying to be irreverent and fun at the same time too, and it ended up weird and creepy instead. Rather than being cuddly, the chunky, shadowy teddy bear graphics look like they’re carved out of sick wood. The cartoony sound effects are clipped, grainy, and abrupt; the bears have nasally high-pitched voices interspersed with groans, shrieks, and whooshing noises.

It speaks loads about the game’s stylistic choices that its cryptic, unresponsive controls are barely unusual by comparison – just another peculiarity in a game that already feels entirely off. (I couldn’t begin to offer any thoughts on its balance as a fighting game. Aerial attacks and throwing in the corner both seem a little strong?) You had to register Grizzly to get a full list of the game’s special moves, so most of their input commands have been lost to time; as best as I’ve found, there’s a fireball-style move where the bear throws their own head, plus a backwards-charging moving that catapults the bear forward like a spring. The computer opponent also periodically teleports, accompanied by an alien warp sound, somehow conspicuously out-of-place even in Grizzly.

What is this game?! How did the tone get so far off? A later version of Grizzly (version 1.3) went in another direction, adding new characters, like a giraffe and a koala, and trading the ominous style for a neon psychedelic jungle aesthetic. But it still kept the scary pounding music, the startling sound design, and the general sense of rigid unease.

It wasn’t supposed to be intense either! Adding to this patchwork of moods and ideas, the game carries a moralistic, religious message from Adam Winiecki, who, in a section of the game that also includes bible quotes, warned against playing the game for the sake of violence:

Grizzly was intended to be as peaceful as possible for a combat game. This is because I find violence to be without humility, and accomplishing nothing. Motivation for playing Grizzly should be to have fun competing with another player using reflexes and strategy, and not to see the bears fight.

Grizzly attempted to be benign. With its radically inconsistent tone, it failed into something weirder, scarier, ferocious, and way more interesting – a question mark, with bears.

Trivia!

An even more updated version of Grizzly with seven characters, possibly including a komodo dragon, and (reportedly) a combo system was available on the iOS App Store; that version has since been removed, presumably by Apple in a purge of older apps.

Download

Version 1.3 of Grizzly can be found on most Macintosh game websites. The earlier version 0.4, which most of this post is based on, was uploaded by Vintage Apple Mac as a compressed Stuff-It file.

How wonderfully bizarre. Thanks for sharing this with us all, Phil