Puppet Motel

In her spoken word performance “White Lilly,” Laurie Anderson remembers a feeling that can’t be easily distilled: “Days go by, endlessly, endlessly pulling you into the future.” Not good or bad, simply a recognition of time going forward, clumsily.

Laurie Anderson’s only game, Puppet Motel, is like that quote – an observation, not necessarily a judgment, of the world moving and dragging us with it.

She recites that quote in Puppet Motel as part of a longer scene. The next time we see the artist, she’s facing us, sitting down in a starkly lit room to tell the story of Plato’s cave, the allegory of people who, “just like us,” can only see shadows of real things. Those two moments don’t share an immediately clear relationship. They are fragments of a larger, blurry picture, pieced together from excerpts of Anderson’s work and original multimedia art, a convoluted reflection on our changing relationship with art, technology, time, memory, and each other.

Puppet Motel belongs to a wave of games created by performers who, right as CD-ROM software caught fire in the mid-90s, tried to adapt their art and their style for an interactive format. That ended up being a dead end for some of them: Jump: The David Bowie Interactive CD was essentially a fancy tie-in ad for Bowie’s new album, and he hated it.

In an interview with CD-ROM Interactive, Anderson said she liked the CD-ROM format because it was still clumsy. “I like the early phases of stuff when it looks like it doesn’t quite work,” she said, and she “wanted to make something that was about the back of your mind,” something that jumps around with free association like “the way my own mind works.” Anderson found an artistically meaningful partnership with The Voyager Company, an early CD-ROM software pioneer that explored digital publishing and “new forms of expression.” She collaborated with designer Hsin-Chien Huang, who has since become known for electronic installation art.

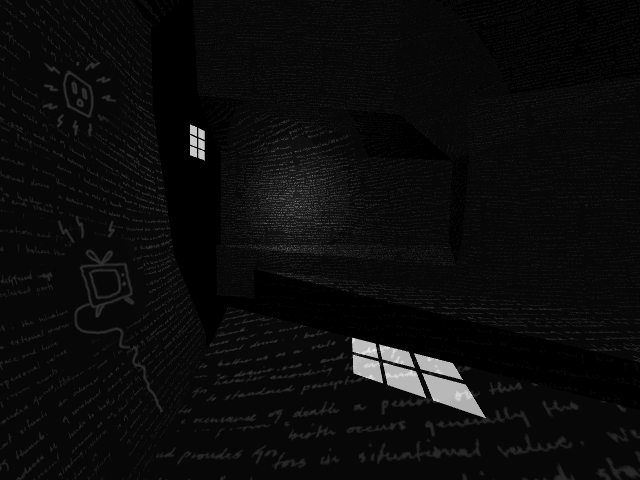

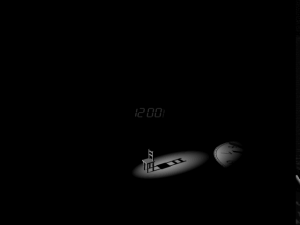

You can think of Puppet Motel along those lines – as a large, interactive exhibit to walk through. The game consists of about three dozen interconnected scenes set in frightening, dramatic rooms. They’re often monochrome, sometimes lit by a single light. As you click around the scenes, poking at random props, you discover hidden snippets of art and conversation, like a poem, a question, a book, or a memory. The game truly meets the definition of multimedia, combining music, video, live action, text passages, and computer graphics.

Elements from Anderson’s performances, like the skates from “Duet on Ice,” are reused for new meaning and haunting visuals

Many of these are excerpts from Laurie Anderson’s art, like the performance of “White Lilly,” recontextualized with other multimedia art. One room features Anderson, appearing as a live-action video, explaining the stage layout from the tour she was performing at the time. Anderson looms heavily over Puppet Motel, if not always directly on-screen then at least narrating or whispering in the background. Yet unlike a vanity project like Prince Interactive (and its lavish Prince-trivia-themed mystery mansion), you don’t need to be familiar with Anderson to play Puppet Motel. Her art career is being repurposed for the game’s own ideas, and not every scene references her earlier work.

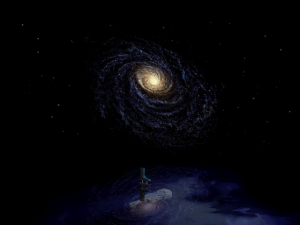

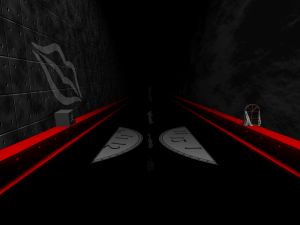

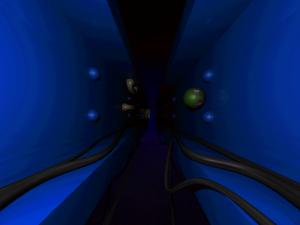

What stand out more are the game’s monolithic, imposing locations. They’re worth playing for by themselves. The game has no distinction between real and surreal elements in its scenes, whether a motel room or an infinitely long hallway. It views them with the same awed confusion. They bear down on the player, dwarfing you in lonely, hazy spaces overrun with darkness.

One object keeps appearing in the darkness – a glowing power outlet. It lingers ominously in the background. On the title screen, it emits a distorted howl, like some sort of digital wolf marking its territory. It’s a icon for electricity. Electricity is always there. And by extension, technology is always there too. When Puppet Motel was released in 1995, the computer age was in full force. So the game fixates on the increasingly constant presence of technology and how it shapes our lives. What does it mean for our lives to become more digital, more electronic?

From Anderson’s eye, as we shift from physical to digital, society gets more abstract. She makes a silly but potent argument in a monologue in Puppet Motel that Nixon invented “cyberspace” by ending the gold standard, the system where the American dollar was backed by a large supply of gold. Regardless of the merits of that choice, it disconnected our currency from physical objects, “leading the way into a world that becomes […] more and more made of numbers, more and more… invisible.”

The scenes in Puppet Motel are torn by that dynamic. Abstract spaces (a dark thicket of telephones and wires) lead into real ones (a lounge room). Digital objects crowd out physical objects. Phones constantly ring as a electrical distraction.

One of the game’s funnier depictions of the shift to digital is the Mac Make Up Version 0.1.02, a fake state-of-the-art handheld computer. For all its fancy specs and its high-color display, it turns out just to be a makeup set. It isn’t too far from the absurdity of WiFi-connected blenders or lightbulbs.

Surprisingly, despite Anderson’s embrace of technology – she made a multimedia CD-ROM! – the game has a skeptical take on it. Or at least sympathy for the tangible world. Consider the motel room mentioned earlier: the television in the room is stuck in a loop showing some inane video, and a projection of a twitchy radio dial covers most of the screen. It’s a bunch of electronic noise. But if you click on the motel’s bed, from under the covers, you can drag out a story about an imagination game Anderson played with her sister. The objects you can touch have meaning beneath them. It mirrors the way Anderson describes the stage from her tour, where “stories about the past, stories about memory, and things you can’t change” are hidden in the back.

Over and over, the game portrays technology as untethering us from reality and suggests that, as we adjust to that change, paying closer attention to the physical world helps us hold onto human connections. Like Anderson said, we’re stumbling into the future, seeing only shadows. “You’re walking, and you don’t always realize it, but you’re always falling,” she says elsewhere. “You’re falling and then catching yourself from falling.”

The room that best expresses this viewpoint has an in-game word processor. You’re given a list of options: you can write a novel from scratch, or you can edit War and Peace. There is absolutely no way anyone would do either of those. But the game can offer those giant ridiculous tasks, so it does. (“Look at all the amazing things you can do with a state-of-the-art CD-ROM! You can fit a whole book on here! So now you have to write one.”) Or as a third option, you can write a short letter on stationary to a friend. “It seems like there’s never enough time to just sit down and write a letter, or even a note,” Anderson asks. “Did you ever really thank her for what she did? […] Why not just do it?” Puppet Motel suggests that the bottomless potential of computers can pull us away from each other, and we can still find those human connections if we make the effort.

This probably sounds backward-thinking. Distrust towards technology is not a daring or original idea. (How many more times do we have to hear someone complain about how phones are ruining society?)

To get an idea of where the game is coming from, read the lyrics to the original song that inspired Puppet Motel. It compares people in the digital world to puppets, “trapped in a digital jail,” having empty “virtual sex.” At the end of the song, the narrator, resigned, joins their joyless pleasure. Yet the game avoids being an anti-technology screed because it embraces the playful side of computers and how they warp reality. Isn’t it wild that you can edit War and Peace? Whatever its implications, technology is pretty neat.

Between scenes, sometimes a text-to-speech, artificial voice will warn you to save your progress. “Save.” “Save now.” Is something wrong with your computer? “You are out of memory.” It’s clearly a joke. There isn’t even a way to save. I don’t know if anyone fell for it at the time, but considering how new and unfamiliar multimedia home computers were, it’s possible somebody did. The game likes that it can mess with you by messing with your expectations of its format.

Its sense of humor comes from a period when computers were a novelty taken more literally. Decades later, it seems kinda old-fashioned, but in a way that reinforces Puppet Motel‘s wary interest in technology. If you press the Escape key to try to quit the game, you literally escape to a secret room, a pun that could’ve come out of an 80s book of cheesy computer jokes. (Puppet Motel was not alone in this. See the title of the horror-themed game Stephen King’s F13. Groaaan.) But the secret room is an attic, filled with abandoned, worn-out props from the rest of the game – almost like they’re trying to get out of the program too. Once again, the glowing power outlet hovers against the wall, and the focus comes back to the tension between physical objects and the digital world. That’s a lot of mileage to get out of a corny interactive pun.

Puppet Motel is a loving critique of itself, basically. It thinks about the effects of computers by using all the bells and whistles of a computer. It wonders about what happens when we use the tools that made a CD-ROM game possible in the first place.

Honestly, Anderson’s way of approaching those questions is hard to follow. Her artistic voice in Puppet Motel is outwardly difficult, even confrontational. The game tests your patience with long, aimless spoken word performances and scenes drowned in darkness. It looks menacing, like it’s daring you to figure out what it means.

This also helps the game’s themes unravel with much-needed subtlety. It can’t be blunt. Its observations aren’t direct; they aren’t spelled out in any one room. Some areas of the motel don’t seem to touch on them at all. Instead, it’s a mood that you see develop across the whole game, a restlessness and bemused anxiety that underlies each scene, each television, each ringing phone, and it becomes more visible as you explore further.

You might find something else resonant in there. A game so fractured and evocative as Puppet Motel welcomes, even demands a different reading, perhaps about preoccupation with memories or its interest in what draws us to divination like palm reading and Ouija boards.

If a message doesn’t connect, Puppet Motel still works as a series of expressive vignettes to click through. Like an abstract, digital future, Anderson and Huang’s vision is all at once dark, confusing, desolate, and beautiful.

Trivia!

Laurie Anderson and Hsin-Chien Huang collaborated again, over twenty years later, for Chalkroom, a virtual reality experience also built around the player exploring fragments of stories in what Open Culture describes as “catacombs” and “dark labyrinths.” Sound similar?

Anderson’s full interview with CD-ROM Interactive is worth watching for insights into her collaboration with Huang and her general thoughts on games, CD-ROMs, and interactive art. She compares her work to other CD-ROMs, particularly to Voyager’s Marvin Minsky: The Society of Mind and to the various musician CD-ROMs where you can play around with the tracks on their songs. “I have to remix my own things,” she says, “so it doesn’t seem fun to remix somebody else’s.”

Pingback: Puppet Motel: o game de Laurie Anderson - POP FANTASMA

Hi I have downloaded this and am very intrigued to play it but can’t get it working on Windows 7 after retrieving it (for free) from Archive.org – any advice?

I still have a Mac copy of this and recently fired up an old Mac laptop to play it. I was so amazed again by the depth and complexity of this piece. I am sad that there is nothing like this made any more.

Among my resolutions for 2022 is to break out from storage an old Mac (the Mac “All-in-One,” a sort of Bizarro-world predecessor to the first iMac, marketed to schools and not the general public) that I retired under OS 9 early in the present century, and poke around Puppet Motel again.

There was some ingenious work being done in CD-ROM interactive thirty years ago, and I think the very limitations of the medium served as a spur to the artists’ creativity. Like Bill in 7/21, I regret that the contemporary interactive product is slick and facile measured against something like this Anderson/Huang collaboration, which makes up in smarts what it lacks in visual polish.

For another original contribution to CD-ROM, see also “Gadget: Invention, Travel & Adventure,” released around the same time, although not in PM’s league.

The one criticism I have of Laurie doing this project is that the format went on to become obsolete with updates to OS systems over the years (Mac itself did away with built-in disc players which screwed over anyone relying on CD-ROMs for file backups) and I’ve tried to find any sort of online emulation that will work with it. (It’s one of a few 1990s-era Mac apps that have, for me anyway, become “lost art”. Another is a game in which Tim Curry plays Dr. Victor Frankenstein and there’s also a music/astronomy hybrid by one Dr. Fiorella Terenzi that I wish I could play again, as well as a CD-ROM art piece (I forget by whom) based on Alice in Wonderland). I keep hoping that someday Laurie releases the audio/video/graphic files for Puppet Motel so the work can be enjoyed again and preserved. But it’s like how her Home of the Brave movie has yet to see release on DVD – it’s unlikely to happen. What I remember of Puppet Motel, it certainly is worth the effort to try and retrieve, though sadly I have to draw the line at tracking down a working 1990s-vintage Mac!

I just went through Chalkroom yesterday at MASS MOCA. A very nice update of Puppet Motel. I wish I remember what I did with that darm cd-rom from so long ago!

Anybody has a copy of it that I could play in IOS? you could sen to my email: karin.iturralde@gmail.com

I value how the article focuses on actionable insight. It reinforces that efficient disposal systems are a key part of successful project execution. Skip services provide dependable support during large cleanups and renovations.

hire skip