Noir: A Shadowy Thriller

Private eye Jack Slayton kept a file on Charles Winthrop, a philanthropist with something to hide. Winthrop’s prize horse Pegasus died, and Slayton suspected an insurance scam. In his notes, he mused, “I’ve had a few horses die on me too, usually in the stretch.” He has the voice of a stock hardboiled detective, cracking a stereotypical case of corrupt wealth, working on a nondescript street in Los Angeles.

As far as Noir: A Shadowy Thriller is concerned, that’s perfect.

Like the name implies, the game is a tribute to the noir genre, the idealized version that pop culture remembers – stories about a gumshoe drifting through decadent clubs and dim alleyways, swept up in the city’s rotten underbelly. For a CD-ROM game especially, it’s a feat of tone and setting.

You don’t actually play as sardonic detective Jack Slayton. He’s gone missing. You’re his friend, tracking him down by following his unsolved cases. You get his office, his informant, and his resources without also having his bad reputation around town. In a way, you get to play tourist to the detective genre.

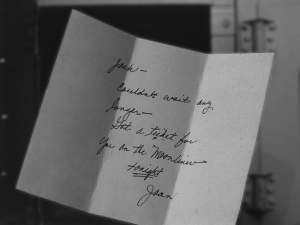

It’s quite a pulpy story. There’s MacGuffins, of course, a set of books with passwords disguised on the bookplates. There are Nazis trying to infiltrate US intelligence; an aging silent film star clinging to her fame and her beloved dog; a bartender with a handy memory for faces; and a lounge singer with a mysterious past named Joan LaFontaine who ensnares everyone she meets. One plot thread centers on the Scheherazade, a palatial resort run by the seediest manager in Los Angeles. The legendary Bradbury Building, famous in film noir, makes an appearance. Two characters have a long goodbye on a train platform right before one of them skips town. This is the romanticized film noir, drawn from the spirit of Raymond Chandler.

Noir also embraces the era’s racism. A chunk of Noir takes place in Chinatown, which the game presents as an exotic danger, a mysterious, dirty, foreign neighborhood separate from civilized areas of the city. Your contact in the Chinese crime syndicate, Charlie Kwan, speaks in broken English with a gross caricatured accent that your character makes fun of. That was an aspect of 1940s film and media, but the game doesn’t consider that maybe it shouldn’t imitate that too. It’s painful to see it rehash those easily avoidable stereotypes.

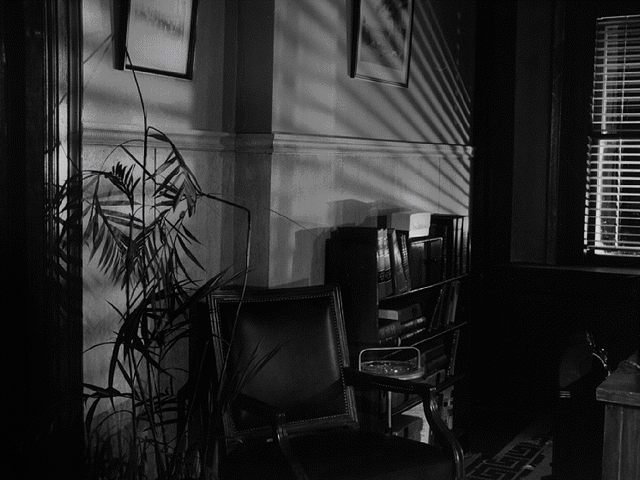

With that aside, the production is spectacular. The game uses black-and-white photography, combined with computer graphics and digital compositing, to create the sights of the mythical old modern Los Angeles. The game’s budget must have been substantial: based on the credits, the developers hired a company to build actual physical sets for Noir. They’re staged in shadowy chiaroscuro lighting, reverently weaving in and out of shots from real-world locations. (The game’s help file provides background on all the historical places you visit.) Scenes like the dusty hallway outside Jack Slayton’s office gave me goosebumps. It really is like stepping into the gritty haze of an old detective film. The game’s director Jeff Blyth had previously directed several of the Circle-Vision 360° travel videos for Walt Disney World’s Epcot World Showcase, and his interest in tourism place-setting comes through in here too.

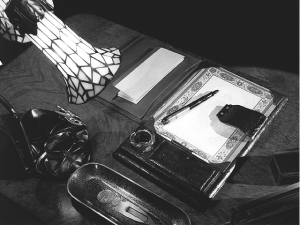

The game world is defined by its fussy, tactile locations. Inside the Scheherazade, the rooms are covered in antiques – seemingly someone’s extensive real-world collection that the developers photographed. You’re always meant to be looking for clues, but the rooms are also there for you to gawk at up-close. Noir loves getting you to rummage around, whether in a room stuffed with artwork, a bookstore, or a desk drawer filled with office supplies.

The black-and-white visuals are perfectly suited for the format. Older computer operating systems were limited to displaying 256 colors onscreen at once. Sometimes this works against realistic-looking adventure games with full-color graphics, but it gives Noir a range of greyscales to work with. It looks crisp and deep, even in areas where the lower quality of the digital graphics can be more obvious. It adds a filmic quality to the live-action cutscenes, which might have looked cheap in color.

That makes the actors’ better-than-average performances seem more authentic than in other live-action FMV games. When the cryptographer Phillip Watkins, caught in a dangerous affair, sheepishly confesses in the most old-fashioned way that “There’s no fool like an old fool,” actor Frank Ertl gives it an appropriately awkward, natural tone. While that could appear stilted in other circumstances, his performance benefits from the weight of the monochrome video, filmed on location on a porch rather than in front of a green screen. The film reel of the missing heiress Alicia Smythe and her overbearing father is heartbreaking because it looks like it could easily be any random family’s old, emotionally fraught home movie. Jeff Silverman steals the show as the slimeball blackmailer (and all-around shitty guy) Myer Goolsby; you can’t trust a single word out of his mouth.

Rooms are dense with objects of the people who live there – artwork, antiques, glassware, personal effects

This approach does have significant drawbacks. Navigating in Noir is unnecessarily difficult. I don’t want to blame the use of photographs entirely, but it’s possible that the developers were limited by what photos they took (from the sets and real places) and had to work the game’s navigation around them. The game’s images have a narrow field of view that can obscure your peripheral vision and isolate you from your surroundings. Some of the photos from the streets of Los Angeles are taken at such skewed perspective that you’re mostly facing a wall. There are so many places you can stand and so many angles you can look from. It can be hard to move to a specific spot, and sometimes you have to approach them from a particular direction that’s not clear. It gets in the way of the game’s storytelling. In one scene, I had to escape from an apartment after my informant told me that police were coming. Despite the urgency, I had to spend several minutes milling around the apartment until I found the exact right position that allowed me to see the exit.

The upside is that Noir tries to usher you to the next step once you’re ready. When you find the combination to Jack Slayton’s safe hidden in his desk, the game will automatically input it for you. Hailing a cab will take you to the next location in your current case without having to choose it manually from the map. That’s the sort of game Noir is: it would rather that you get lost in a room in the historic Oviatt Building than stuck on a puzzle.

It’s easy to get mixed up in the noir story, and the game attempts to keep you on track. Jack Slayton left behind six case files. They seem to be unrelated, but over the course of the game, they converge in unexpected ways. Secret identities are revealed, a character is murdered, and a missing dog in one case shows up in another story trained by Nazis to steal military secrets. You can work on each case individually, and they overlap at some points. If you get stuck on one, you can jump to another and pick up your place later by reading the notes in your journal about what you’ve learned so far.

When you hit a major revelation, the soundtrack leaps in with a dramatic stinger, a rushing string section, a muted trumpet, or another excellent noir-y music cue. (The smoky, curling flute theme that plays for clues related to Joan LaFontaine has been stuck in my head for days.) The music fits the drama of the scene, and it has the bonus effect of letting you know you’ve found a clue and can keep going. It cleverly uses the aesthetics of noir to keep up the pace.

But sometimes, the game loses track too. The progress notes in your journal may reference events from other cases that haven’t happened yet. The game might repeat exposition you’ve already seen in another case or assume you’ve learned about something that you haven’t. To complete the game, you need to close all six cases, and the one I saved for last – Charles Winthrop’s dead horse – was the only one not tied to the bigger story. Evidently, this was the incorrect order. So I tied up every loose end with the Nazis and Jack Slayton’s gambling debts, and the game hinted at the detective’s imminent return, but it still wasn’t over because I had one more piece of unrelated business.

The confusing plot reminded me of an anecdote about Chandler’s novel The Big Sleep. At one point, a character’s chauffeur is murdered, and the book never resolves who killed him. When asked who did it, Chandler didn’t know either – and he didn’t seem to care. It can be fun to get confused by a shifting noir story and let the plot take you wherever it runs. When Noir‘s controls cooperate (and when it stays away from the unwelcome aspects of the genre), it’s terrific to get caught in the game’s web-like story too. In large part, it owes that to the exceptional production design, how it transports you to the 1940s Los Angeles that never really existed but we’ve always remembered.

Trivia!

Noir also has multiple difficulty modes – a rare, unusual choice for an adventure game. It impacts how many clues you can get from your informant over the phone, as well as whether your cursor indicates when you can interact with an object. I can’t imagine who would disable that context clue, especially in such an intentionally cluttered game, but at least it’s an interesting experiment in how to offer difficulty levels in a narrative game.

Sounds exactly like the thing I’m looking for. Thanks for sharing, now I definitly want to play this!

where can I find this game online?

You can find this game for download on The Internet Archive