Atmosfear: The Third Dimension

The popularity of VCRs in the 80s and 90s led to the odd trend of the video board game. It would come with a VHS tape – later, a DVD – that would have atmospheric sounds and visuals to put on in the background while you’re playing. During the game, the video would announce special events, like some misfortune happening to the current player or a change to the board or the rules. Often, you had to win and turn off the tape before time ran out, adding a sense of urgency.

They’re a sign of the importance of home entertainment to the era’s culture and consumerism. There was, inevitably, a Star Wars video board game, as well as a regrettable game called Rap Rat which tells you everything you need to know about it and you should absolutely not click that link to the video.

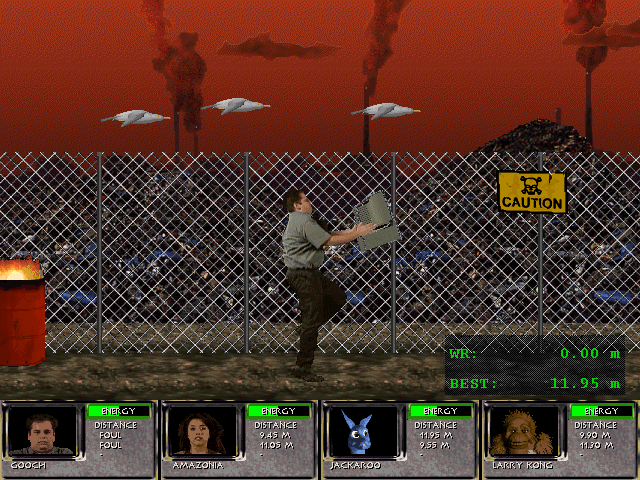

One of the more successful video board games may have been Atmosfear, also called Nightmare, a series of horror games featuring characters inspired by infamous figures from folklore, history, and legend competing to escape from the afterlife. Much like video board games accompanying the rise of the VCR, when the CD-ROM became a big deal, Atmosfear made the leap to computers too, taking inspiration from the medium-defining ideas from Myst and similar titles released around then. Atmosfear isn’t a smooth fit for all of those ideas, and this version of the game makes for an interesting case of what’s gained and lost in reworking a board game for a computer. » Read more about Atmosfear: The Third Dimension