Learn about game preservation (and play Mac games) at Super MAGFest 2018

Hey, I’m coming back to MAGFest!

Super MAGFest 2018 is right around the corner on January 4-7, 2018 in National Harbor, MD. It’s a unique, freewheeling experience and my favorite gaming event.

I’m so excited to share that this year, I’m hosting the panel Preserving Video Games and Gaming History.

We’ve brought together an incredible panel of experts for you, featuring game archivist Rachel Donahue, International Center for the History of Electronic Games curator Shannon Symonds, and Video Game History Foundation director Frank Cifaldi. We’ll go over the basics of game preservation, some of the trickier questions, what’s being done right now, and ways that you can help.

The panel will be at 4pm on Friday, January 5th in MAGES 1 as part of the MAGES educational panel track. (I’m still sort of in disbelief that this is happening! Huge thanks to the panelists.)

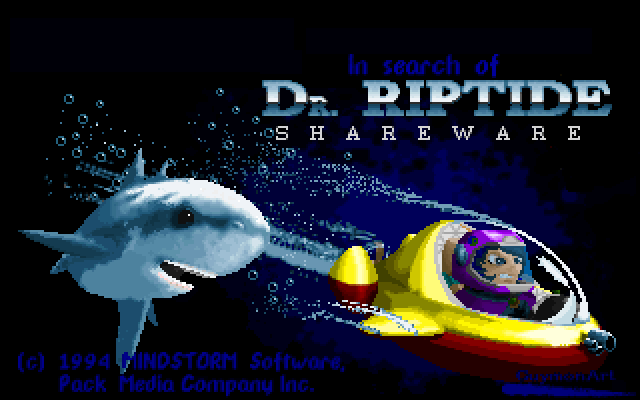

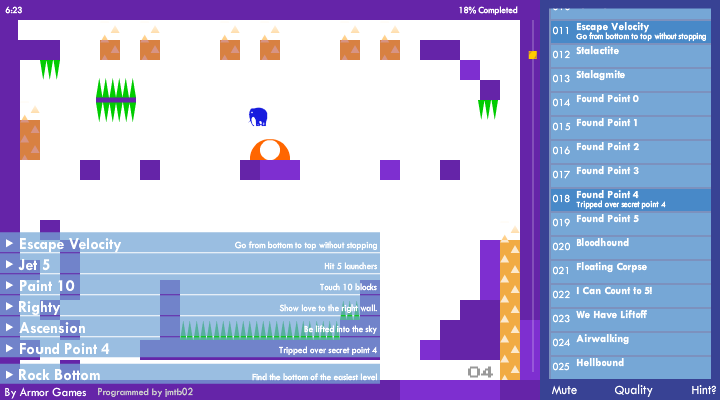

Also! I’m curating a selection of Macintosh games for the MAGFest Museum. My goal was to get a range of moods, styles, and genres. Attendees will be able to play a variety of titles including The Journeyman Project, Theresa Duncan’s Smarty, Bungie’s early shooter Pathways into Darkness, the zesty RPG Realmz, and a whole bunch of educational games. (And, at long last making its debut at MAGFest, Catz!). It’ll be lots of fun to bring these games to new audiences.

If you’re going to MAGFest, please come to our panel! And at any point over the weekend, reach out if you want to talk about Mac games or just to say hello.